Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

Abdul-Rahman Abdullah and Abdul Abdullah are brothers and artists. Although their practices are distinctly their own, they both work across multiple forms, exploring memory, family, migration, transformation and Muslim identity, creating works that make statements equally affective and political.

We caught up with Abdul-Rahman and Abdul to ask 20 quick questions about their life and art experiences, and about their new exhibition Land Abounds at Ngununggula, which also features work by Tracey Moffatt.

1. Your first art love?

Abdul-Rahman: My first art love was Hergé, the creator of Tintin. His work seemed to capture a sense of reality with such an austerity of line and flat colour, everything was so precise yet full of drama.

Abdul: When I was very young my mother would take me to the Art Gallery of WA in Perth when she went into the city to go to Lincraft. There I discovered a giant panoramic painting by Juan Davila. It was visceral and exciting, and exposed me at an early age to what art could be.

2. Was there a moment when you realised you wanted to be an artist?

AR: I always wanted to draw for a living for as long as I remember. After many crappy jobs I finally became an illustrator, designer and commercial sculptor before I realised that I needed to be an artist. I went back to art school in my mid-thirties after my brother had graduated and have never looked back.

A: I watched my older brothers in art school as I was growing up, but I only decided to be an artist when I picked up an elective in art in my third year studying journalism at Curtin University. In my final crit, the lecturers spent ten minutes speaking about a discarded, melted Crunch bar I had decided not to eat and had left in front of my paintings. They gave me a high distinction for it and I never looked back.

3. Your fondest memory of each other growing up?

AR: I knew my brother from the day he was born, I’m almost nine years older than him. He was always a very clever and very cute kid who seemed to be planning his adulthood from the moment he could walk. I used to compete as a boxer when I was in high school, we used to put on gloves and I’d get on my knees and just let him belt me as much as he liked. He’d get right into it and I loved it. My brother followed me into boxing later on just like I followed him into art.

A: I really liked punching my brother, but also what I would really love to do is wait for my brother to get tired in the afternoons and then I would pull out the Lego. That was the time of day he was guaranteed to play.

4. Your most humourous memory of each other growing up?

AR: My brother was a constant source of entertainment for me, he could always hold his own from when he was very little. Unlike me, he was a very fussy eater and mum would quarantine all the bananas in the house for his consumption only. They were one of the only things he’d eat. When he was in the bath, busily telling himself a story, I’d eat a banana and throw the peel at him. When he stood up to vent his rage I‘d shoot him with a water pistol full of ice water. I found it pretty funny, but mum was always on his side and I’d get in trouble. It was worth it.

A: When my brother would look after me when I was little he would tell me scary stories about the ‘soup factory’ (a derelict warehouse) down the road that made soup out of little kids. He would then pretend to hear a knock on the door from the ‘soup factory men’ who were there to get me, and he would get me to hide in a cupboard until he was sure they were gone. This would take care of all babysitting duties! [Laughs]. When I was in primary school he would also take my homework out of my bag and write swear words through it for the teacher to find. I got him back—accidentally—at school when the teacher gave us the talk about the harms of smoking, and I proudly raised my hand to say that my brothers only smoke out of coke bottles.

5. Best advice you’ve been given about making art?

AR: A good friend and mentor to both of us, the legendary Richard Lewer, once told me that every work must answer the question “So what?” Why would anyone be interested? It can be a scary proposition but I need to answer this question with every work I ever make. If there’s no answer then the work has failed.

A: Someone told both my brother and I to be the audience as much—or more—than being artists. To me this said to get involved with the community, and see and support as much stuff as we could, and I think we’ve both taken this to heart.

6. Your exhibition Land Abounds at Ngununggula features your works alongside Tracey Moffatt. What do you find inspiring about Moffatt’s work?

AR: Tracey is an icon. The way she uses the dramatic tropes of popular culture to hold a mirror to society, she reveals who we are by showing us who we think we are.

A: I have always been inspired by Tracey’s vision and purpose. Her work is layered, personal and heartfelt, while at the same time conceptually rigorous and hard-hitting. I saw her work Other at the 2011 Singapore Biennale, without knowing it was even hers, and it immediately became my favourite work ever.

7. What will you be exhibiting for Land Abounds?

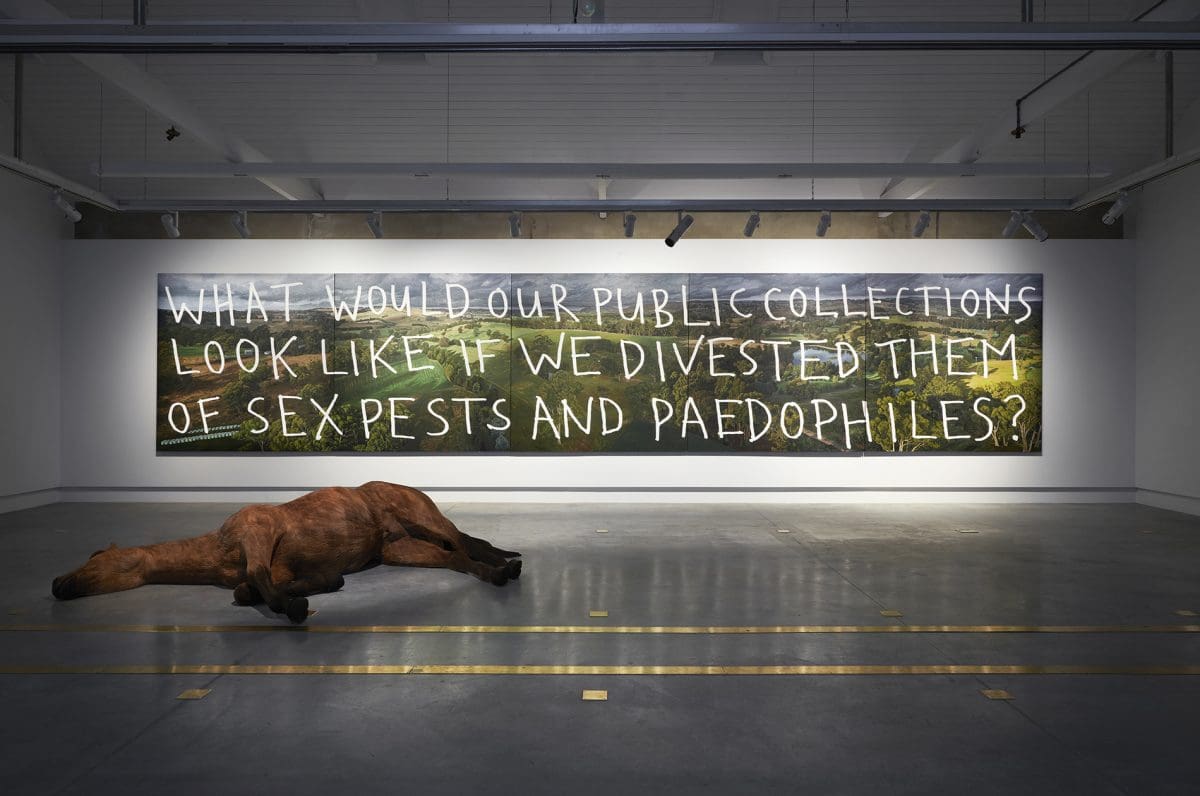

AR: I will be showing an immersive installation called The Dogs from 2017, alongside a new work titled Dead Horse that was made earlier this year.

A: I will be exhibiting a series of embroideries made with the assistance of DGTMB Studios in Yogyakarta, as well as a new 10m panoramic painting titled Legacy assets.

8. How do you think your works can not only be understood against each other, but also alongside Moffatt’s works?

AR: This show is an ongoing conversation between the practices of my brother and I, brought to bear on the enduring legacy of Tracey Moffatt. It’s the point of cultural intersection arrived at through very different material avenues.

A: A big part of our respective practices has been looking to, and honouring the relevant artists that came before us. To be mentioned in the same sentence as Tracey is an honour, and I’m happy to surf in the wake.

9. In different ways and in different forms, both of your works have explored Muslim identity particularly in a mainstream Australian context. What have you come to learn or understand through this?

AR: I’m very interested in finding the points of intersection between my particular perspective of the world and the world around me—whether cultural, political, mythical or natural. Those points of overlap provide the friction where magical things happen. My Muslim identity is a big part of that and I love frustrating those who think they know what that means.

A: After a decade of this, what I’ve learned is that no matter what we do or say, or put out into the world, there are always going to be people that have a fantastical idea about who we are in their heads, and hate our guts for it, and will let us know at every chance they get.

10. Why is art such a valuable way of thinking about identity?

AR: Every one of us brings a lifelong rambling inner dialogue, personal mythologies and contradictory self interests to bear on every situation ever. Art clarifies these things for a moment and shares glimpses of that wet bag of synapses for other people to experience. Art is an enduring record of who we were at that moment, it identifies us.

A: For me art serves a similar function to journalism, without being burdened by objectivity. It has given me a platform to be as emotional and reactive as I want to be. While my work certainly has interrogated identity, it’s less about who I am, and more about challenging what people think I am.

11. If you could collaborate with any artist, dead or alive, who would it be?

AR: My brother.

A: My brother.

12. Quick advice for young artists?

AR: Back yourself and back those around you. Make work about what you love and work with those you love.

A: Find a community and get involved. Working in a group is so much easier. Share opportunities and resources, and lean on each other to achieve your goals. A rising tide lifts all boats.

13. Best time of day to create?

AR: My ideal day is admin first thing in the morning, studio stuff up to and around midday, a bit of carving and then kids in the afternoon, and more carving at night. I stay up late and get up early. My wife Anna Louise Richardson is also an artist and we have three kids aged 4 and 2 years, and one is 8 months, so we have to schedule everything around their needs, wants and whims. Honestly, the best time to create is whatever time you have.

A: I am a night owl, so later afternoon and into the late evenings is best for me. The morning is for sleeping and admin.

14. Classic ‘Abdullah brothers’ drink order at the bar?

AR: Iced coffee.

A: Anything with Lychee in it.

15. Do you think about the viewer when creating and how they may receive or experience your work?

AR: I nearly always work at 1:1 scale, for me the viewer completes the work by occupying the same space. My work usually comes from very specific places but I’m quite happy for people to run wild with how they respond or relate to it. I want my work to spark off memories, moments and mythologies, and if people want to discover more they can.

A: Every time. I think we have to. It’s not just about what we are communicating—that’s only half of it—it’s who we’re communicating to and who is the work in service of? From the beginning of my professional and public practice I’ve known not only is my work not for everybody; for some people it is outright unwelcome.

16. Beauty or politics?

AR: Beautolic pouts?

A: Beautiful politics

17. An art experience that’s stuck with you?

AR: A public artwork that I made in 2015 became a small, impromptu memorial after the Christchurch Massacre in 2019. I felt so privileged to have inadvertently provided a space for worlds to overlap with respect. I think about it a lot.

A: In 2012 I travelled to Brisbane to meet Vernon Ah Kee, and he introduced me to Richard Bell and Gordon Hookey. It was the best day of my life, and changed the way I approach art.

18. The most interesting thing someone has said to you about your work?

AR: Lots of people have told me how much they cried in the presence of one particular work. Again, it’s a real privilege to provide that space for people.

A: A politician in Sydney wrote in 2011 that I worshipped a moon god and wanted to convert young Australians.

19. Are either of you good cooks? Any signature meals?

AR: Haha, I’m not a great cook but I love to cook. My soul food is Malay curry but I’ve had to simplify and diversify with three fussy little ones.

A: My brother is a much better cook than me. I’ve only taken it up in the last couple of years. I make a mean scrambled eggs.

20. Best colour to create with?

AR: Wood.

A: Black.

Land Abounds

Abdul-Rahman Abdullah and Abdul Abdullah, with Tracey Moffatt

Ngununggula

28 May—24 July