Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

It only takes a few seconds for me to put my foot in my mouth when speaking to artist Lorraine Connelly-Northey, about the late assemblage artist Rosalie Gascoigne. When I mention that their work is similar, Connelly-Northey is quick to respond, “Similar? What about our work is similar? I always push back against this idea.”

The National Gallery of Victoria’s joint exhibition surveys work by the two artists, who both use found materials collected in regional environments— but Connelly-Northey displays a healthy scepticism about the pairing. Her protestations make sense, especially since she’s been fighting the comparison for 30 years.

Ten years ago, Connelly-Northey finally had a good look at a work by Gascoigne when the two artists were paired in an exhibition at McClelland Gallery and Sculpture Park. She was relieved. “What was I so worried about?” she asked herself, unable to see the resemblance.

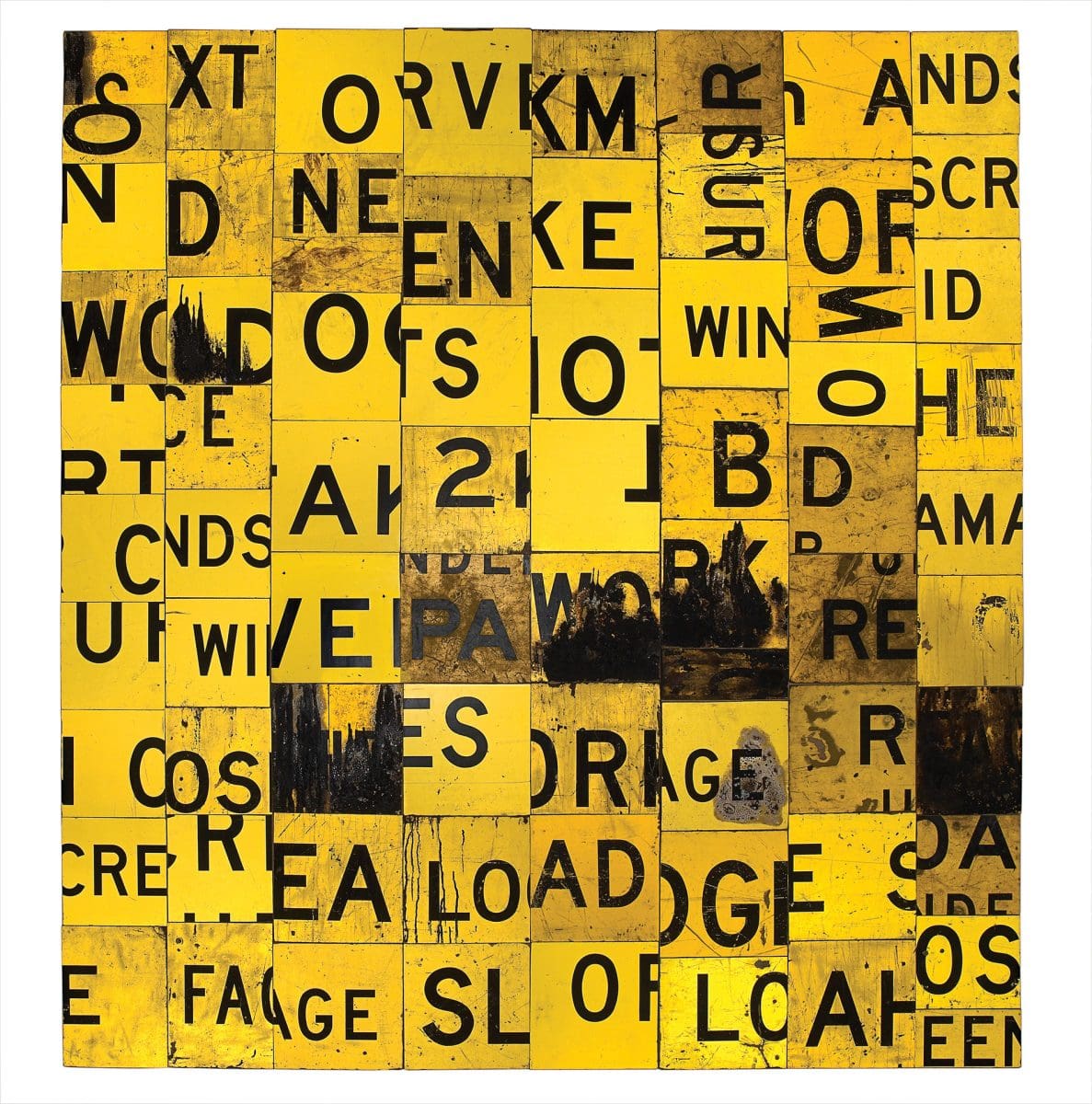

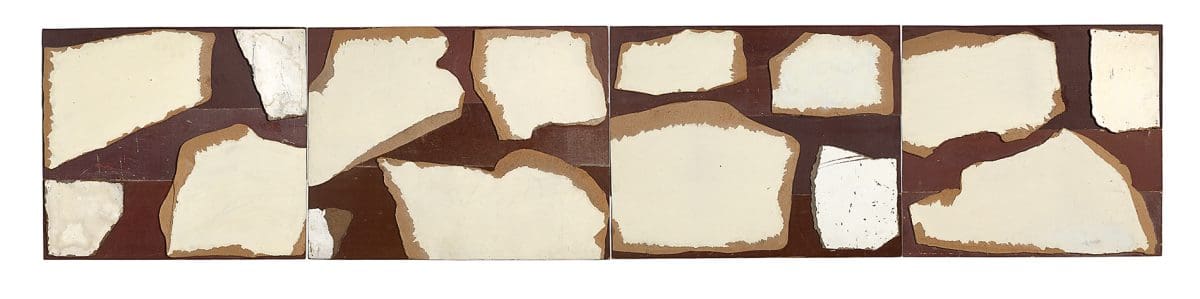

Gascoigne, who died in 1999, had a relatively late start to her career—she held her first solo show in 1975, at the age of 57—but quickly achieved widespread acclaim as a master of assemblage. Collecting her materials on the outskirts of Canberra, she was preoccupied with the patterns made by the refuse she found. Her work often features rhythmical arrangements that invariably transform her hard materials into something softer, something calm and neat.

Connelly-Northey, who has extensive knowledge of what can be found in an 80-mile radius around her hometown of Swan Hill in western Victoria, scavenges junk like Gascoigne did—but for her, that is where any similarity ends.

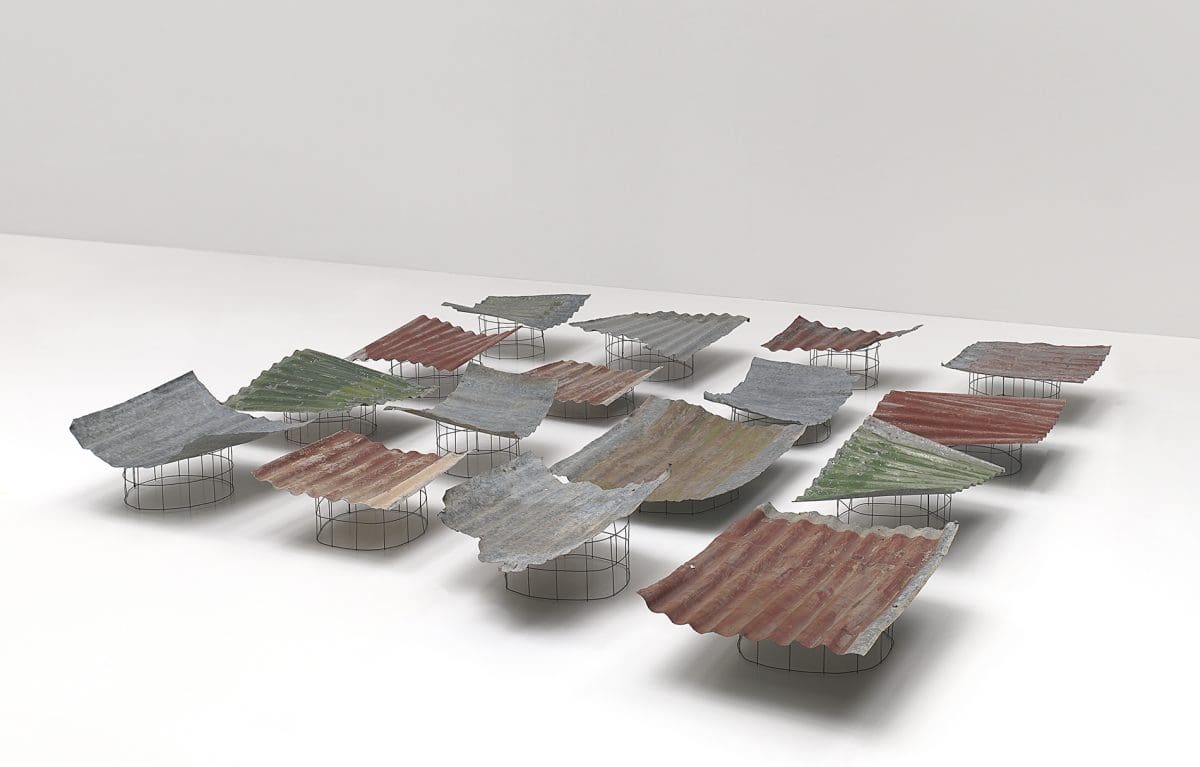

Connelly-Northey’s artworks are made with hard materials—barbed wire is her signature—but her work does not tame this hardness. If anything, she makes their toughness even more pronounced. “There’s nothing lovely about it,” she says when we discuss her barbed wire. “I try to leave sharp bits on each work”. From Waradgerie (Wiradjuri) and Irish heritage, Connelly-Northey was trained in traditional Aboriginal weaving techniques. Some of her earliest works at the NGV are from an unforgettable 2002 series of koolimans and string bags. Her versions of these vessels are created from rusted and twisted metal. Despite the rigidity of her material, Connelly-Northey forms it, moulds it, even weaves it, in a process she has described as “tormenting” and “frustrating”.

While her vessels are undeniably tough, their final forms are astoundingly charismatic. On many of her sculptures Connelly-Northey hangs organic material–feathers, snail shells, quandong nuts or bits of driftwood–that sit like jewels along the jagged edges. She repeatedly suggests people might find this, or the humble size of the works, “cute”. This charming quality is intended; it is the way that the artist draws her audience into the piece. She makes her work attractive because, ultimately, Connelly-Northey has a difficult message to deliver us.

“I’m inflicting pain,” she says of the sharp edges on her sculptures, “to kick you in the guts.”

She wants her work to recall violence, aggression, human debris and “skeletal remains”. Her sculpture is devoted to Australia’s Indigenous history, and the difficulty of weaving with salvaged junk is her comment on the ongoing violence of colonisation. Connelly-Northey has had to transform the traditions of female master-weavers; and every work, from her small vessels to her enormous wall collages, is a uniquely feminine, Indigenous response to physical, emotional and generational pain.

As a prominent Indigenous artist, Connelly-Northey is used to feeling the heavy weight of responsibility. She is a perfectionist who expresses a strong ambition to get her work “as right as I can, because I’m accountable to Aboriginal Australia”. However, in this major NGV showcase, she feels a new responsibility—for Gascoigne, who is no longer here to frame her work. “The show is about us, not [just] me”. For a long time, Connelly-Northey had not wanted to look too closely at Gascoigne’s work, keeping it in her peripheral vision. Now she needs to face the elder artist head on. She speaks of preserving Gascoigne’s spirit in the room with her when she thinks about the show.

Throughout her entire career, Connelly-Northey has kept Gascoigne at bay. She was disturbed (“burdened”, as she puts it), in the way artists often are, by the comments that sought to compare her to another sculptor. But during our conversation she concedes a fascinating, unexpected similarity between them. Both artists began creating art through floristry. Gascoigne famously came to sculpture through her study of Ikebana, the art of flower arranging that was taught to her by Japanese artists. As a young artist, Connelly-Northey’s study of weaving obviously involved an education into the local plants that were suitable for the art form, but she also served her community by making funeral wreaths and arrangements with non-traditional material such as wire, bullock horns and dried flowers.

Connelly-Northey is now in her late 50s, the age that Gascoigne was when she began her art career. The joint display of their work at the NGV gives Connelly-Northey a reason to approach Gascoigne as a colleague. Perhaps this exhibition will allow audiences, finally, to put away superficial comparisons between these two titans of assemblage art and appreciate not their shallow similarities, but the deep and profound differences.

Found and Gathered

ROSALIE GASCOIGNE | LORRAINE CONNELLY-NORTHEY

The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia

3 November–20 February 2022

Please note NGV Australia is currently closed in line with COVID restrictions, but will reopen on Wednesday 3 November.

This article was originally published in the September/October 2021 print edition of Art Guide Australia.