Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

Ashleigh Garwood is drawn to dramatic landscapes: the frigid majesty of glaciers, the caldera of volcanoes, deep ruptures in the surface of the planet; places that have an otherworldly ambience. But the photographs she presents in her solo show, Massing, are literally not of this earth. Or rather they are and they are not.

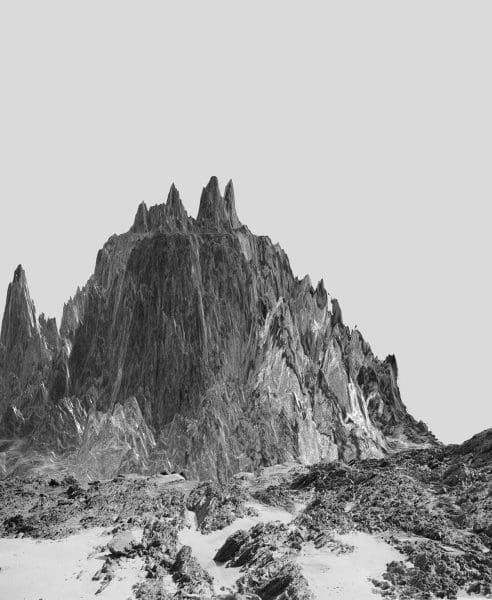

While the bare, impossibly sheer cliff faces in her monochromatic images may resemble Icelandic vistas, their origin is far more prosaic. Garwood shoots analogue black and white film near Batemans Bay on the New South Wales South Coast at a location that reveals the results of tectonic upheaval some 200 million years ago. Then, using u3-D modelling software, she harnesses the power of digital technology to create her own landscapes concocted from equal parts fantasy and reality.

Garwood’s technique adds a SFX aesthetic to her photos, but it is the notion of ‘world building’ that really gives her work its strong sci-fi edge. Creating fully formed new worlds is, after all, one of the strengths of the genre. And Garwood’s photos do resemble a much more elegant version of the crazy visions of interstellar landscapes that adorned sci-fi pulp fiction covers in the 1950s and 1960s. However, Garwood’s scenes are missing the multi-tentacled monsters and heavily gendered, stereotypically sexist representations of heroic men with phallic ray guns and helpless women bursting out of their bustiers that were the stock and trade of science fiction illustrators of that era. In fact, Garwood’s landscapes are almost utterly devoid of life.

With the exception of Untitled_IslandA, 2017, in which a rocky atoll manages to support two stunted gnarled trees, Garwood pictures a mineral world; a zone in which organic life holds no sway. And this emptiness, accentuated by their sci-fi aesthetic, is what gives Garwood’s images their power. For science fiction is a forward facing genre and even though we no longer blindly accept the veracity of the photograph (living as we do in the post-Photoshop age) the artist nevertheless seems to have somehow photographed a post-apocalyptic future. Perhaps because her process is already a clever combination of fact and fiction, it only takes a small leap of imagination to read Garwood’s overtly fantastic photos as straight reportage.

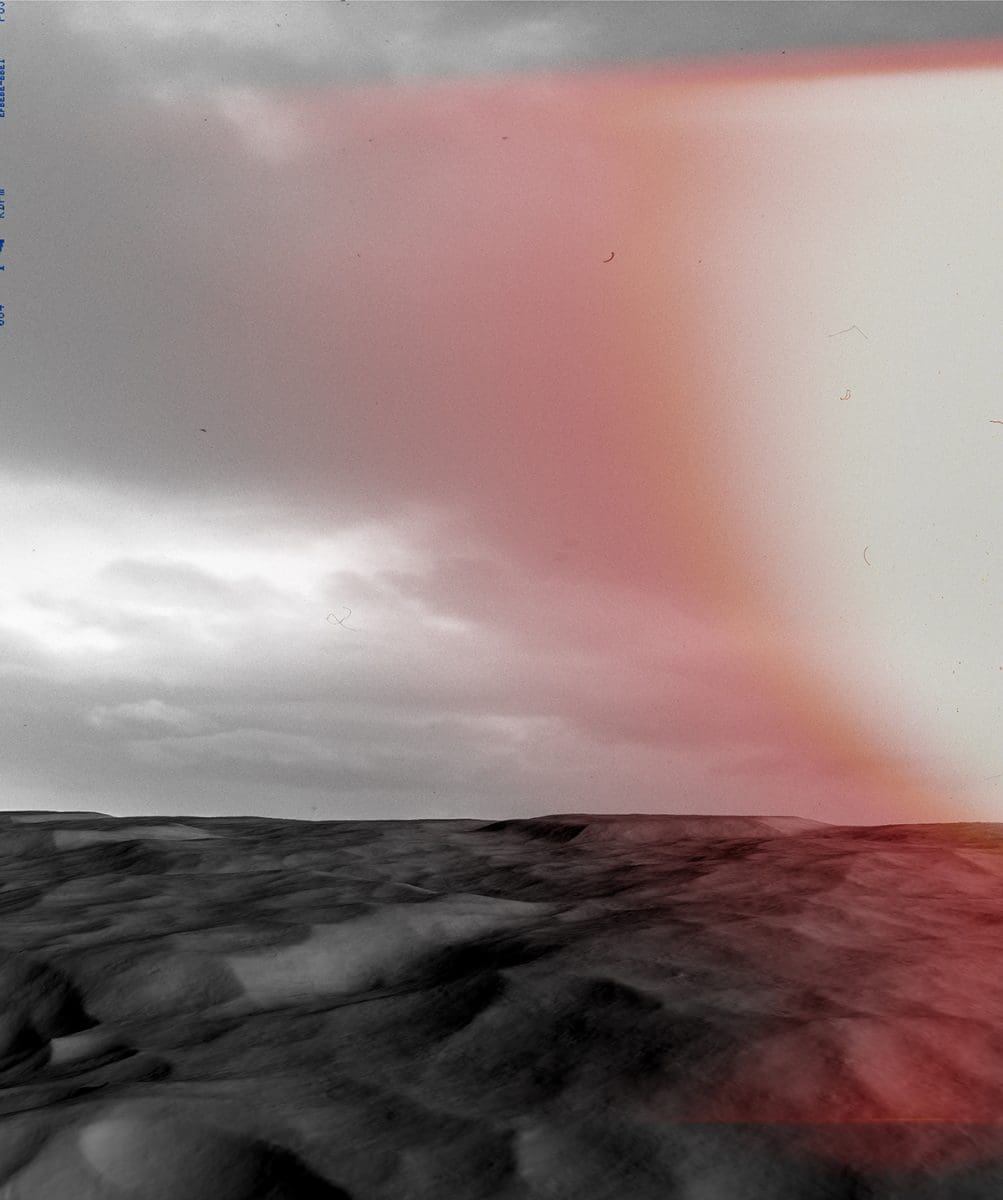

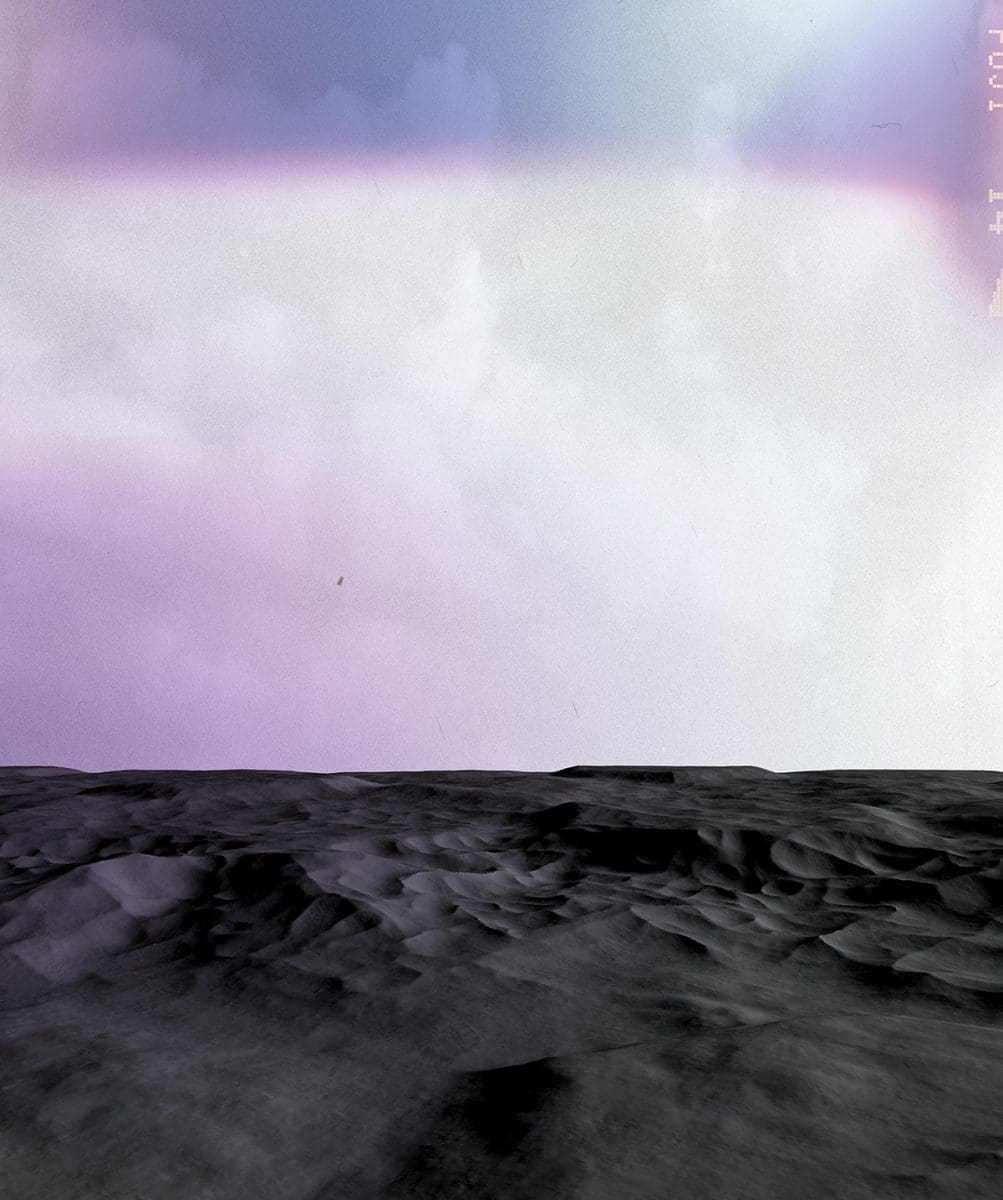

The future she documents is barren and desolate, a blasted landscape in which nothing survives or at least nothing that is visible to the naked eye. If there are life forms eking out their existence among the precipitous peaks of Garwood’s 2017 FORM and Retaining Structure series, or on the undulating black plains wind-swept by chemical-coloured storms captured in her Land_Editor series, then they are microscopic. Ashleigh Garwood pictures a future that is bleak and beautiful, but not (quite) inevitable.