Piercing the veil

A new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary finds a rich complexity in the shadowy terrain between life and death.

Reproduction items and image from The Umbrella Movement Visual Archive, 2014, installation view (detail), 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art. Courtesy the Umbrella Movement Visual Archive. Image: Document Photography.

Left: Yuan Goang-Ming, The 561st Hour of Occupation, 2014, installation view, single- channel video. Courtesy the artist. Image: Document Photography. Right: Reproduction items and image from The Umbrella Movement Visual Archive, 2014, installation view, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art. Courtesy the Umbrella Movement Visual Archive. Image: Document Photography.

Clockwise from left: Ellen Pau, Diverson, 1990, single-channel video, 5:30. Installation view, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art. Liu Ding, A Sentence, 2016, poem, installation view, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art. Sarah Lai, Rub it until it is removed, 2015, single-channel HD video, 5:40, installation view, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art. Sarah Lai, Polish your own shoe as long as you can, 2015, single-channel HD video, 11:11, installation view, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art. Sarah Lai, Demarcated area, 2017, performance with installation. Dimensions variable, installation view, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art. Luke Ching, 150 Lost Items, 2014, mixed media, installation view. All courtesy the artists. Image: Document Photography.

Luke Ching, 150 Lost Items, 2014, mixed media, detail installation view, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art. Courtesy the artist. Image: Document Photography.

Reproduction items and image from The Umbrella Movement Visual Archive, 2014, installation view, detail, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art. Courtesy the Umbrella Movement Visual Archive. Image: Document Photography.

Swing Lam, Temporary structure research in Umbrella Revolution 2014-2016, 2016, works on paper. Installation view, detail. 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art. Courtesy the artist. Image: Document Photography.

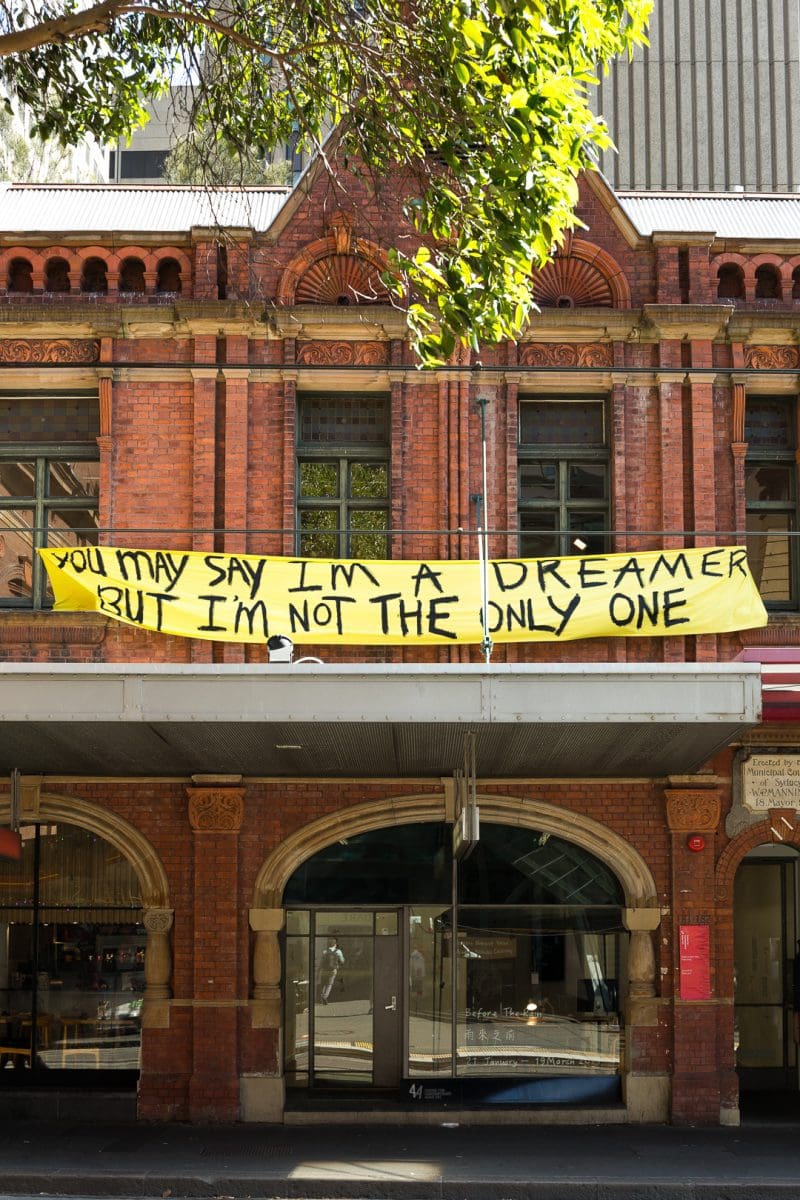

Reproduction item (banner) from The Umbrella Movement Visual Archive, 2014, installation exterior view, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art. Dimensions variable. Courtesy the Umbrella Movement Visual Archive. Image: Document Photography.

In September 2014 our news screens and feeds were filled with images of Hong Kong’s high-rise streets thronged with tens of thousands of protesters. Variously known as Occupy Central, the Umbrella Movement or the Umbrella Revolution, massive areas of Hong Kong’s CBD were unable to function for weeks as a result of peaceful actions. The protesters, mostly young people, were fighting for universal suffrage: the right to elect their own government representatives. They used umbrellas to shield themselves from tear gas and pepper spray, and camped out for 79 days.

It’s not surprising if for most Australians, this event is no longer at the forefront of our minds. News cycles are fast and unforgiving, and since the Umbrella Movement our screens have brought us news dominated by massacres and terrorist attacks in Martin Place, Paris, Nigeria, Kenya, Tunisia, Orlando, Bangkok, Ankara, Beirut and Brussels amongst others; ongoing war in Syria; the #BlackLivesMatter movement; and Donald Trump’s presidential campaign and subsequent inauguration. You could be forgiven if September 2014 has faded to the background of your mental newsreel.

With the group exhibition Before the Rain, curator and 4A director Mikala Tai seeks to reignite conversation around this important regional event.

Before the Rain brings together a selection of archival material alongside works by intergenerational Hong Kong artists who address themes of control and dissent. Downstairs the focus is on the protests themselves, and Tai, who grew up in Hong Kong, worked closely on this section with artist-activist Sampson Wong of the Umbrella Movement Visual Archive. Visitors are invited to explore hand-drawn signs, ephemera and an online archive. James Kong’s birds-eye time-lapse videos, captured via cameras he hid in tins around the protest area, and Swing Lam’s maps and sketches of barricades, give a sense of the scope and ingenuity of the protests.

When we speak, Sampson Wong discusses the increasing importance of artists in a protest context, especially with the visual immediacy of social media sharing. However, he adds that “this combination of creativity and protest has not been new since the Civil Rights Movement, since Paris in 1968.” Protest art has a long and complex history, a lineage that connects the hand-drawn A4 flyers of the Umbrella Movement with political graffiti on the walls of ancient Rome.

Upstairs, Sarah Lai’s Demarcated Area, 2017, deploys the international, institutional language of the rope barrier as a mechanism of control. Being arbitrarily herded through these labyrinthine queue markers is nothing new, but during a performance at the exhibition opening hired security guards shifted the barriers at timed intervals. They interrupted those viewing artworks or listening to speeches with apparent disregard. Lai’s work reminds us that these controls are in place all around us, even (and most insidiously) when we don’t notice them.

Diversion, 1990, by Ellen Pau, created in the aftermath of the Tiananmen Square massacre, features archival government footage of a 1960s swimming race in Hong Kong’s Victoria Harbour. The jumping, diving, swimming masses of bodies suggest mass-scale subservience and obedience, but also waves of migration, hope and naïveté.

A Getty Images photograph that was widely circulated during the 2014 protests is presented alongside these works. In this image, police holding red banners that read ‘Stop Charging or We Use Force,’ form a rigid human barrier around a loose group of peaceful protesters. In response, protesters made a selection of playful banners in the same format, with messages in Cantonese and English including ‘Stop Discriminating or We Will Give You a Warm Hug’ and ‘Stop Charging or We Screw You in the Corner.’ Reproductions of these banners are exhibited, a reminder of the creativity and good humour that made these protests remarkable. These playful messages perhaps best convey the Hong Kong identity that the protesters sought to wrest from underneath nearly two centuries of occupation.

Before the Rain

4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art

Until 19 March