Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

The first piece in Art Guide’s new ongoing series, On The Couch with Andrew Frost, is custom built for social distancing. While we’re sheltering in place, now is a great time to consider movies about art and artists. Fire up the streaming service, grab some popcorn and enjoy. A dedicated cinephile, Andrew Frost offers several viewing options, some better than others.

Artists on Film: Serious satire and life lessons for free

by Andrew Frost

When you start to compile a list of art movies it quickly becomes apparent that there are two broad categories. On the one hand there are biopics – dramatizations of the life of an artist. On the other hand there are movies about the art world, sometimes based on, or around, real or fictional artists, but just as often using it only as a backdrop. Of these two broad types of art movies there are usually just two approaches: serious drama, or satire.

The problem for art movies is that it seems to be almost impossible for screenwriters and directors to either get the art world right, or if they get it wrong, still make it entertaining enough that accuracy doesn’t matter.

Filmmakers tend to get bogged down in myth making about the importance of creativity and expression, or go off on tangents making fun of things that they don’t seem to understand.

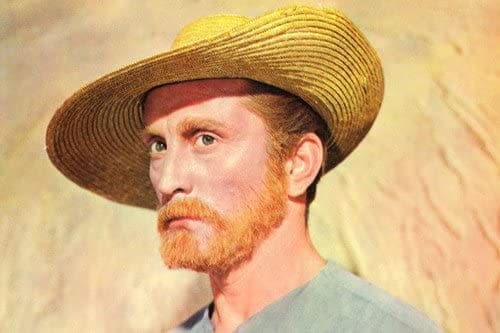

A case in point is the unrepentant myth making in the various treatments of the life of Vincent Van Gogh. It’s a story that multiple directors have turned to, in dozens of documentaries, and in more than half a dozen feature films.

The classic Lust for Life, 1956, is an epic based on a best-selling pot boiler by Irving Stone, and stars Kirk Douglas as the doomed Dutchman. At turns a ridiculous, literal minded and clichéd mess of hammy emotions and grandiose themes, it is at other moments a compelling recreation of the creation of the artist’s best pictures.

But many of the other attempts at telling the story are risible. See, for example, Loving Vincent, 2017, a dubious animated film in the style of Van Gogh’s paintings that goes all in on the myth. Some are notable for their willingness to question the accepted narrative. Robert Altmann’s Vincent & Theo, 1990, in which Tim Roth makes the most of the lead role of Vincent, puts the artist’s life into perspective from his brother’s point of view.

There are dozens of other films about artists and their struggles to choose from if misery is your bag.

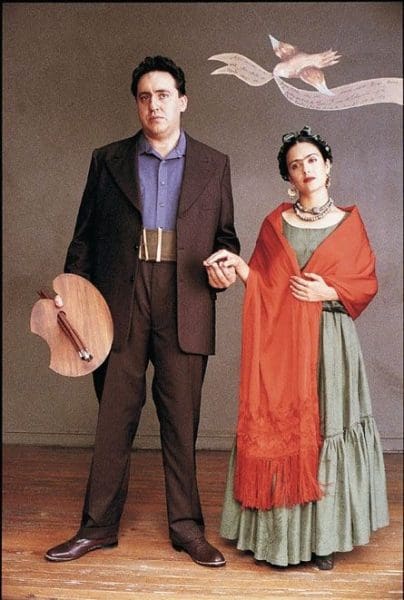

Among the better films are Frida, 2002, with Salma Hayek as the doomed and betrayed artist, and with a great turn from Alfred Molina as the detestable Diego Rivera; the portrayal of the betrayed artist in Artemisia, 1997, which charts the relationships and career of the 17th century painter Artemisia Gentileschi; and the hilariously bad Andy Garcia star vehicle Modigliani, 2004, in which the artist invents long-necked café expressionism and then (yada, yada, yada) dies.

Mike Leigh’s Mr. Turner, 2014, is that rare thing – basically a biopic of JMW Turner’s later life – that also takes its time to portray the 19th century art world with some accuracy, as well as showing Turner making art – something that is, oddly, rare in movies about the lives of artists.

A lot of people rate actor Ed Harris’s directorial debut Pollock, 2000, as the best artist biopic – and it has a ton of on-screen talent, a respectful tone and a great performance by Harris as the artist – but it’s pretty boring and mostly avoids the meaning of the art, instead portraying Jackson Pollock’s doomed obsessions.

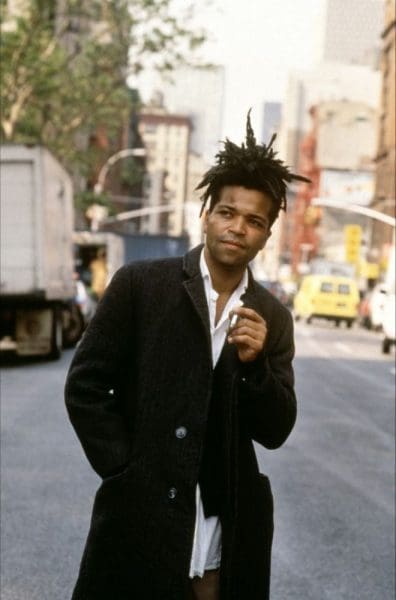

By far the best artist biopic – which really warps the genre into something that at times resembles video art – is Julian Schnabel’s Basquiat, 1996. The film has a number of advantages: the director is an artist who knew Jean-Michel Basquiat, the subject himself is portrayed in a superb performance by Jeffrey Wright, and the little digs and portrayals of art world foibles and hypocrisies come from a place of first-hand knowledge. And best of all? Basquiat is seen in his studio creating the magic – and it works brilliantly.

Fictional artists give film directors far more range to treat the subject however they wish, and satire or comedy is a favourite approach. Two classics are The Horse’s Mouth, 1958, in which Alec Guinness plays a talented but monstrous painter; and Call Me Genius (aka The Rebel, 1961) where a hopeless but determined Tony Hancock strives to make his mark, including inventing new art movements such as shapeism.

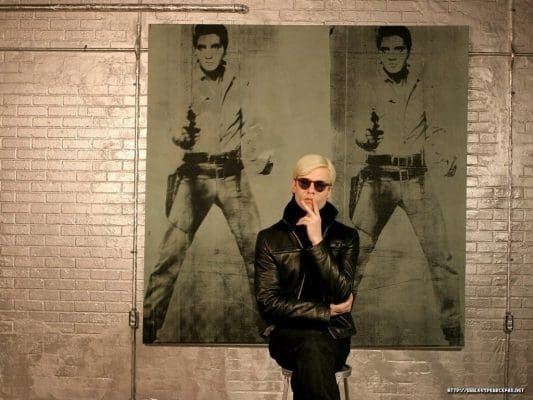

Fictionalised real artists is another art movie sub-genre, and like the treatment of Van Gogh as the classic artist archetype, the on-screen portrayal of Andy Warhol is something directors have used to set the tone of their films and their attitudes to contemporary art.

Oliver Stone’s cartoonish portrayal of Warhol in The Doors, 1991, is a fleeting cameo made brilliant by actor Crispin Glover’s genuine weirdness. And Guy Pearce does a brilliant portrayal of Warhol in the 1960s (wig, leather jacket, shades) and Warhol in the 1970s (wig, sports jacket, clear rimmed glasses) in Factory Girl, 2006. But the best screen Warhol by far is Jared Harris in I Shot Andy Warhol, 1996, an eerily accurate recreation of the artist’s voice and demeanour.

While the art world is evidently of lasting interest to filmmakers, getting the milieu right, or just making it fun, seems to be a daunting task.

John Houston’s 1952 version of Moulin Rouge is unintentionally comical and Baz Luhrmann’s 2001 telling of the wild bohemian life at the landmark Paris nightclub is merely only his second worst film.

Dan Gilroy’s art world satire Velvet Buzzsaw, 2019, was highly anticipated after his brilliant news satire Nightcrawlers, 2014, and although it has a star cast, it lacked insight into the real art world to give it some credibility, and made the mistake of imagining a world in which an online art critic has any influence. Its elements of horror mixed up genres and the whole film feels like a derivative rip off of Driller Killer, 1979, Abel Ferrara’s low budget shocker about a conceptual artist who goes mad and kills people… as you do. A better recent film which uses the art world and a gallery as background is Tom Ford’s Nocturnal Animals, 2016, which has two amazing things: a believable gallerist, and stunning video art.

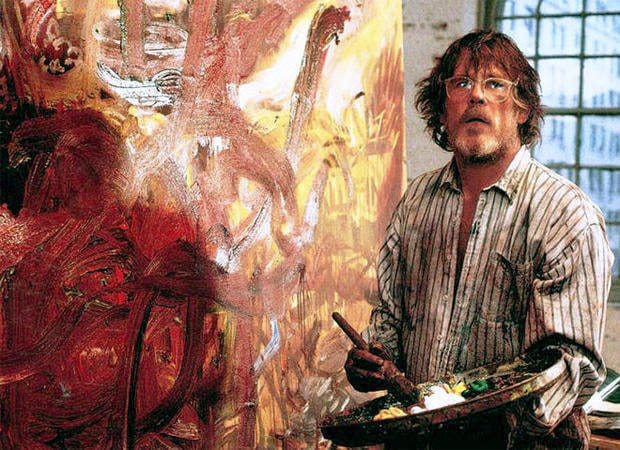

And the best film about the art world? For me, that’s Life Lessons, the middle part of the portmanteau film New York Stories, 1989, directed by Martin Scorsese and starring Nick Nolte as Lionel Dobie, an old school painter adrift in the late phase of New York’s 1980s go-go art scene. It’s about a manipulative painter, his would-be prodigy, a clash of generations, self-delusion, and it centres on the struggle to make a vast painting. And there’s lots and lots of paint.