Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

Nothing is what it used to be in the group show Just Not Australian. This is probably just as well, since the cultural artefacts that form much of the show’s raw material are not always pretty. In works made over the last two decades, the 19 artists have used existing images, materials and meanings to reconstruct and critique Australian nationhood and identity. Also, there’s a lot of swearing.

The cursing is not there for an easy effect, but instead reflects everyday language back to us to suggest a belligerence embedded in our culture. Tony Schwensen’s Tampa-era Border Protection Assistance Proposed Monument for the Torres Strait (Am I Ever Going To See Your Face Again?), 2002, literally tells gallery visitors to “F*#K off” as they walk in the door. Spelled out in three versions on temporary road barricades, the phrases remain an in-your-face model of the xenophobic hostility many Australians face in their daily lives. The barricades triangulate around empty space, precariously propped up in buckets of water and held in place by childrens’ floaties: girt by a sea of suburban backyard entitlement.

This synthesis of appropriated forms and indelicate language recurs in Jon Campbell’s word paintings, and in the 2011-2019 work by seventh-generation Australian Abdul Abdullah in which his title declares, “F*#K off we’re full.” Abdullah screens a single still image: an Australian map overlaid with the titular phrase. Positioned up near the ceiling, the deliberately blurred and amateurish image makes the aggressive slogan look feeble yet persistent, like an outdated pub screen that’s never turned off.

Many works in the show create meaning by transforming existing matter into a new, strongly material presence. In Imperative, 2012, Raquel Ormella transmogrifies a standard Australian flag into something fragile and almost, but not quite, unrecognisable. Barely held together by a remnant border, pierced by scorched perforations and with fallen stars drooping out of frame, this symbol is on its last legs.

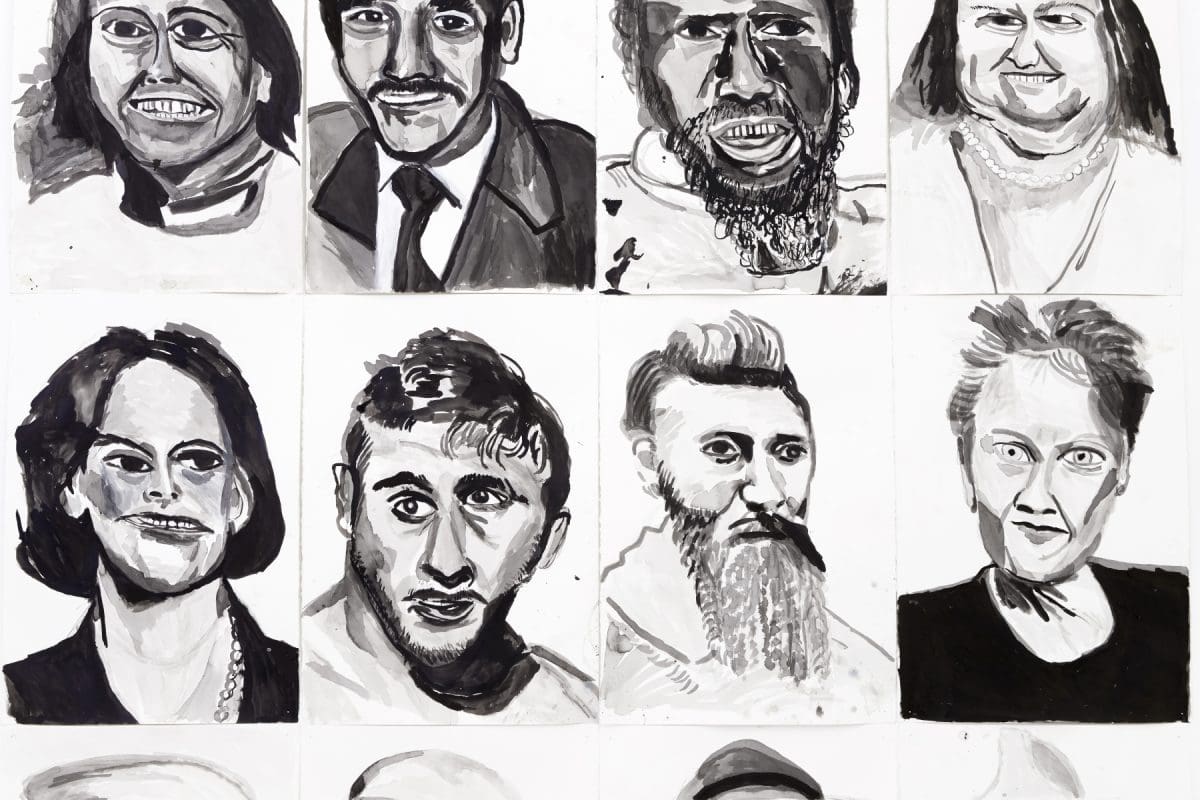

Vincent Namatjira’s 16 gridded ink drawings of powerful and not so powerful figures, Australia in Black and White, 2018, riff off existing portraits to bring a mischievous quality to serious issues of postcolonial representation. Gordon Hookey’s 10-metre-long Murriland! #1, 2015-ongoing, synthesises protest banners, street murals and history painting. Painted on unstretched canvas, its formidable material presence and public scale communicates the urgency of its truth-telling as much as the histories it depicts.

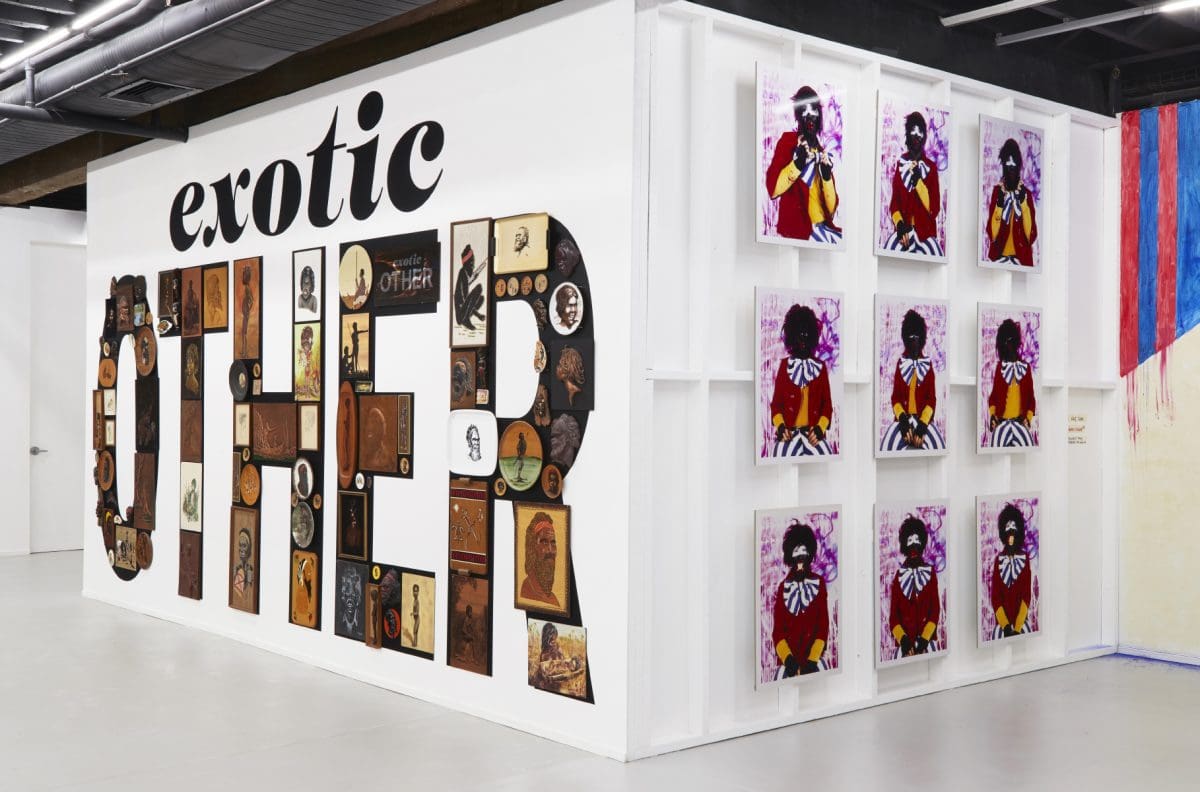

Karla Dickens combines found objects with her own constructions to create a biting expression of Indigenous female experience in Never Forget, 2019, and Tony Albert’s collection of Aboriginalia, exotic OTHER, 2009, strips back the kitsch from retro souvenir plates, copper reliefs and velvet paintings to reveal racist histories hiding in plain sight.

In her 2012 essay, ‘The Digital Divide: Contemporary Art and New Media,’ UK theorist Claire Bishop noted how contemporary viral images exist in a state of what she called “perpetual modulation”. This can be seen here with existing symbols and images transmuted into new forms and meanings. Soda_Jerk’s Terror Nullius, 2018, misappropriates the Australian film and television canon to queer a new classic. Joan Ross also draws on existing imagery for I Give You a Mountain, 2018, an animated speculation on Australia’s relationship with its colonial past and Anthropocene future.

Landing amid the annual Australia/Invasion Day debate and with elections looming, this show declares and counters the racism and xenophobia corroding Australian identity. It’s not a subtle show: the urgent register of many of these works reflects troubled times. But its diversity, inventiveness and critical energy celebrate alternative visions that suggest the possibility of a more thoughtful and infinitely more interesting future for this country’s sense of self.

Just Not Australian

Artspace

18 January–28 April