Piercing the veil

A new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary finds a rich complexity in the shadowy terrain between life and death.

Installation view: 2020 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Monster Theatres featuring Reclining Stickman by Stelarc, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide; Photo: Saul Steed.

Installation view: 2020 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Monster Theatres featuring Pierre Mukeba. Photo: Saul Steed.

Judith Wright, Australia, born 1945, Sightlines, 2019, Brisbane, synthetic polymer paint on paper, found objects, wood, metal; © Judith Wright/Sophie Gannon Gallery, Melbourne/ Fox Jensen Gallery, Sydney/Fox Jensen McCory, Auckland, photo: Carl Warner.

Judith Wright.

Megan Cope, Quandamooka people, South East Queensland, born 1982, Brisbane, Study for Untitled, 2020, rock, violin strings; © Megan Cope/This Is No Fantasy, Melbourne.

Megan Cope. Photograph: Saul Steed.

Brent Harris, New Zealand, born 1956, The Lamp, 2019, oil on linen; Collection of the artist, Melbourne, © Brent Harris/ Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne/Robert Heald Gallery, Wellington.

Performance still: Mike Parr, Australia, born 1945, JERICHO, 2019, Carriageworks, Sydney, clay mask by Linda Jefferyes; © Mike Parr/Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne, photo: Zan Wimberley.

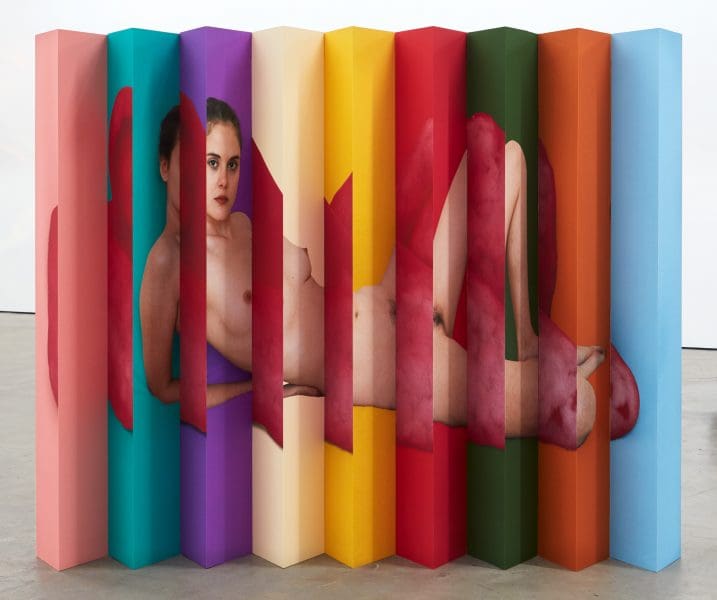

Polly Borland, Australia, born 1959, Giant MORPH 1, 2019, Los Angeles, lenticular print mounted on aluminium dibond; © Polly Borland/Murray White Room, Melbourne, photo: Lee Thompson.

Detail: Abdul Abdullah, Australia, born 1986, Understudy, 2019, Australia, mixed media, dimensions variable; Courtesy the artist and Yavuz Gallery.

Monsters are dredged from our dreams, dropped in there by grief and loss, by dystopian politics and existential threats that engulf the landscapes of our lives and of our minds. In the Adelaide Biennial, celebrating its 30th anniversary in 2020, these monsters emerge, playing out in galleries that become shadow stages of the psyche.

The 23 artists and collaborative groups showing work under the theme Monster Theatres are looking at this current period of “extreme flux”, says curator Leigh Robb, “politically, socially, economically and environmentally”. Thinking of the etymology of the word monster—monere in Latin, for warning or portent—Robb noted a lot of different types of monsters appearing.

“The threat of the apocalypse has always been present, and it feels that way right now, even in the last few months,” she says. “Venice was having the worst floods it’s ever had; there’s tsunamis, there’s bushfires. The environment is sending its own warnings.”

For the exhibition, artist Megan Cope, a Quandamooka woman who keeps a studio on Minjerribah or North Stradbroke Island, has created an installation made from blasted rocks sourced from a geological museum. Creating a sound inspired by the ground-dwelling bush-stone curlew bird, its high-pitched wail might be understood as a harbinger of death.

Lots of violin, double bass and cello strings have been woven around the rocks, Cope explains from Melbourne, where she also spends part of the year.

These strings are attached to industrial materials, elements of extraction, and tree stumps, to create a visual and aural sense of environmental trauma in a work Robb calls a “lamentation for an exploded country”.

Musicians will activate and perform with the installation, inspired by Minjerribah’s controversial history of sand mining. “It really did create a lot of tension, fear and anxiety in our community,” says Cope, “but when I asked my grandmother what she thought, she laughed at me and said, ‘Look, we were here before the mine, and we’ll be here afterwards’.”

Cope also has the large mine at Olympic Dam, north-west of Adelaide, in mind, with its huge copper and uranium deposits. “We’re going into the substrata now, with that type of mining,” says Cope. “If you look at the middens, they were mounds that were overland, and this is a deeper extraction that’s very, very destructive; we know that.”

The theme of Monster Theatres is “really critical right now”, says Cope. “Colonisation is the monster. It’s a machine, it’s a process, it’s a project turning everything that is sacred and sentient into death and trauma.”

Judith Wright’s art meanwhile is often marked by an internalised grief made external; part of an ongoing project to imagine the life of a child who has died. Robb says Wright’s Biennial installation, Tales of Enchantment, continues her shadow play and carnivalesque underworld, with hybrid and mythical composites. “She’s negotiated that loss of a daughter in the work, so there’s an imaginary world for that lost child, and this speculative theatre for Judith has always been a very poetic space,” says Robb.

Speaking from her home in Brisbane, Wright says that her installation will be connected to a series of her works on paper in another room, connected by “flying eyes”—cut-out eyes suspended from the ceiling, as a “symbol of the eternal bosom, with the pupil its child”.

The installation, based on In the Garden of Good and Evil, Wright’s work at Queensland Art Gallery in 2018, has been significantly modified to fit the Monster Theatres theme, with added pieces. The theme is “especially relevant for our turbulent times in that it can incorporate contemporary themes as well as mythological ones,” she says.

Wright’s career as a dancer with the Australian Ballet, prior to commencing her art practice in the late 1970s, has greatly influenced her work, particularly her paintings, installations and video art that are about the body and its relationship to other presences, and the fluidity between the conscious and unconscious mind.

“The ideas seem to come to me out of nowhere, although they often come in the early morning, so I guess dreams have something to do with it,” says Wright. The shadow play around her figures is overtly theatrical. “When I was in the Ballet, [Sir] Robert Helpmann was the director and he had a strong sense of theatre, so that sense of the theatrical and of the unknown has always had an influence on what I do.”

Ballarat-born artist David Noonan, based in London for more than a decade, makes very theatrical, mise en scene collages alongside printmaking, sculpture and filmmaking to create alternative landscapes and encounters. Among his pieces showing at the Biennial are his filmic work A Dark and Quiet Place, 2017-18, which moves between representation and abstraction, as well as his tapestries.

Cyprus-born, Melbourne-raised Stelarc meanwhile has been “really exciting” to work with, says Robb. The performance artist is famed for testing the limits of the human body and exploring the interface between man and machine. Working with Flinders University engineers and various programmers, his new work involves a nine-metre robot that can be choreographed manually, either in the gallery or online, and Stelarc himself will perform within the robot interface five hours a day.

Other artists whose works will be seen at the Biennial include Mike Bianco, Abdul Abdullah, Karla Dickens, Mikala Dwyer, Pierre Mukeba, Polly Borland, Michael Candy, Erin Coates and Anna Nazzari, Julian Day, Brent Harris, Aldo Iacobelli, Mike Parr, Julia Robinson, Yhonnie Scarce, Garry Stewart and Australian Dance Theatre, Kynan Tan, Mark Valenzuela and Willoh S. Weiland.

Robb says these artists were chosen partly because they could provoke a conversation, and through their work are “manifesting the monsters” of our time.

“Monsters embody a cultural moment and they conjoin fears and anxieties,” says Robb, “but also a lot of the artists’ works are propositions of hope or alternative ways of living on this damaged planet.”

2020 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Monster Theatres

Art Gallery of South Australia and Adelaide Botanic Garden

Extended until 2 August 2020

This article was originally published in the March/April 2020 print edition of Art Guide Australia.

Please note that AGSA reopened on 5 June. With public safety in mind, physical distancing, limits to the number of people in the gallery and hygiene measures will be in place.