Material curiosities: Primavera 2025

In its 34th year, Primavera—the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s annual survey of Australian artists 35 and under—might be about to age out of itself, but with age it seems, comes wisdom and perspective.

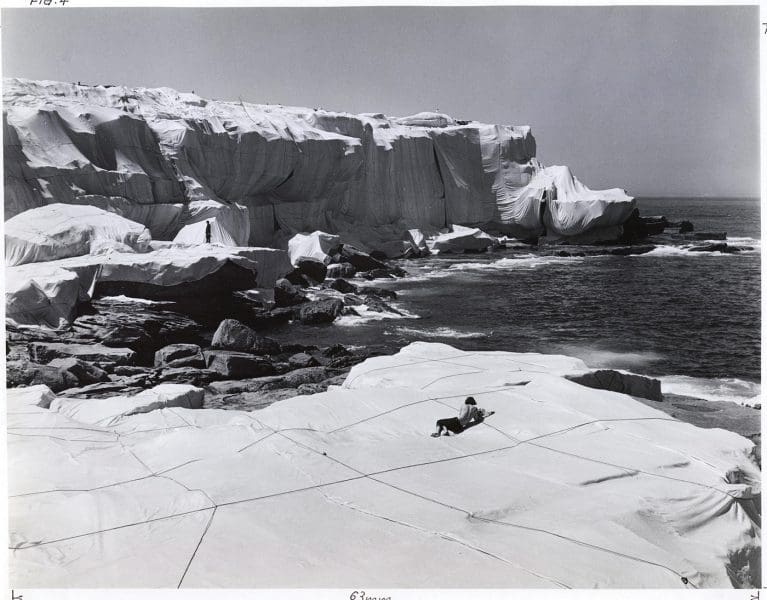

A decade ago, Kaldor Public Art Projects were celebrating 40 years since its inaugural artwork, the seminal and controversial Wrapped Coast by Christo and Jean-Claude presented in 1969. Now in 2019, with 10 more years to reflect upon, the 50th anniversary has a different feel to it, as the intervening years have seen some of the most diverse, boundary pushing, democratic and interactive projects yet.

In this time, a number of large-scale artworks have provoked fervent dialogue and, in some cases, invited contributions from the public. For example, earlier this year American artist Asad Raza allowed visitors to collect for their own use some of his 300 tonnes of soil used as part of his Absorption; in 2010, John Baldessari projected in lights the names of 100,000 people as part of Your Name In Lights. And in 2014, the organisation embarked on a momentous exercise in democratic commissioning, Your Very Good Idea, which saw Australian artists submit proposals for the 45th Anniversary Project, the winner being Jonathan Jones with barrangal dyara (skin and bones).

“My hope for all our projects is that they are accessible and engaging for the public,” says founder John Kaldor. “All our projects are free, and many of them take place outside of museum or gallery spaces. When we work with an artist like Anri Sala to create a project in a busy tourist location like Observatory Hill in Sydney [The Last Resort, 2017], we know that many visitors will happen upon it by accident – it’s this kind of engagement that I find particularly exciting.”

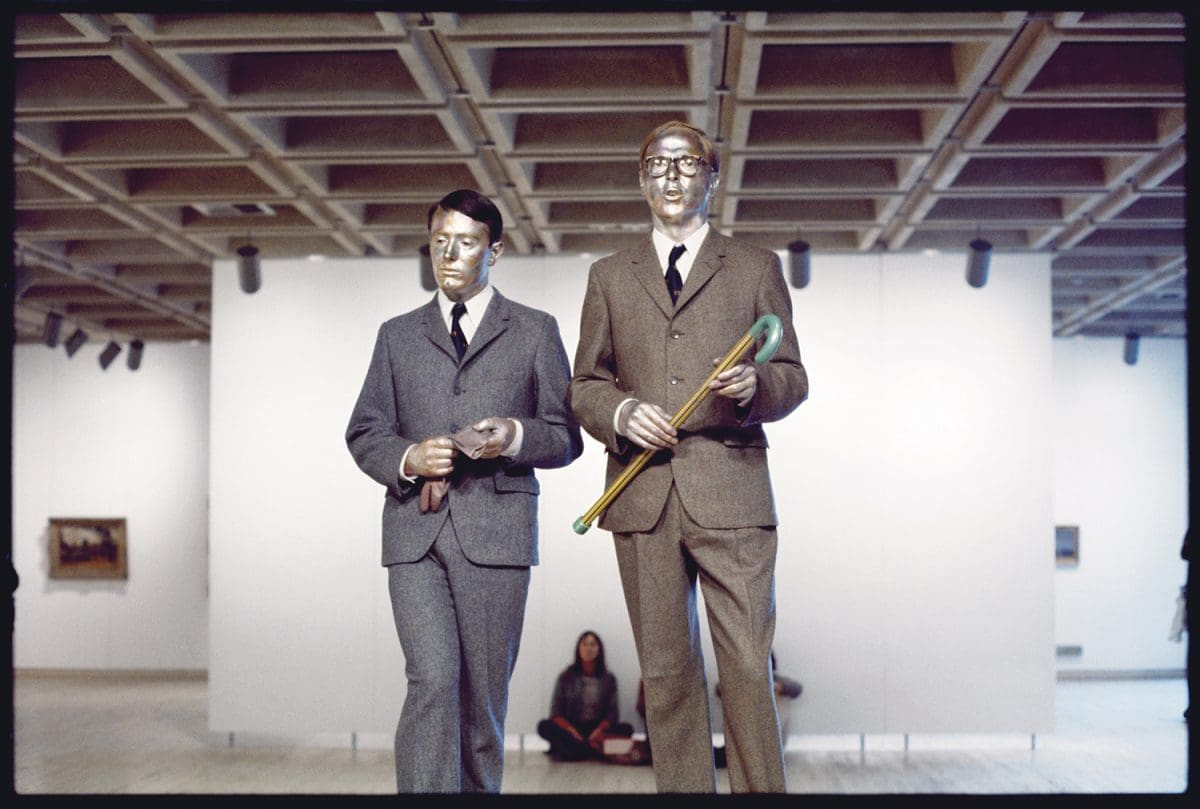

This civic-minded spirit of interaction and inclusivity defines the new Art Gallery of New South Wales exhibition Making Art Public: 50 Years of Kaldor Public Art Projects, created by renowned British artist Michael Landy. His idea was to use ‘remnants’ from half a century of artworks – the physical materials left behind, bits and pieces stored and archived – to create new works that will, according to Nicholas Chambers, coordinating curator for Making Art Public, “transform AGNSW’s Modern and Contemporary Galleries.”

“Despite the disparate locations and scales of the Kaldor projects, Landy has reincarnated each within standard 4 x 4 x 3 metre cubes,” says Chambers. “They resemble oversized archive boxes, but that’s where the uniformity ends. Each box reveals a different way of thinking about the original projects, and about what remains after they were dismantled.”

The remnants that Landy has appropriated fall into two categories: items relating to a project’s gestation, or backstory, and items that emerged from the effects of the project’s realisation. Landy’s materials include postcards, artwork instructions, drawings, photographs, video and much more. And many of these artefacts illustrate Kaldor Public Arts Projects’ dedication to accessibility and openness.

“When looking through the documentation of early projects during the 1960s and 70s,” says Chambers, “Landy commented on the diversity of the audiences visible in the footage. These were projects by young, experimental artists completely unknown in Australia at the time, yet their work was seen by not only ‘in the know’ members of the art world but also by broad audiences including families and schoolchildren.”

As well as the exhibition, Kaldor Public Art Projects is also celebrating 50 years with its Living Archives initiative, which invites members of the public to share their memories of artworks from over the decades. Living Archives grew out of an event held in 2018 for those who had visited Wrapped Coast in 1969, when Christo and Jeanne-Claude wrapped 2.5 kilometres of coastline and cliffs at Little Bay, Sydney using fabric and rope.

Today, it’s clear that Wrapped Coast embodied many of the key values that have defined the organisation since – particularly public engagement. Rebecca Coates, curator, writer and director of Shepparton Art Museum, wrote her PhD thesis on Kaldor Public Art Projects, and believes Wrapped Coast decisively set the tone for things to come.

“We have testaments from artists, for whom the experience changed the course of their professional lives; public figures who railed against the initiative; and, 50 years later, from members of the public who remember the experience and what it meant to see their own country through very different eyes.”

Coates also suggests that the projects initiating the most meaningful rapport with the public need not be those that make a point of intentional interaction, such as those by Raza or Baldessari. The mere fact of bringing ambitious works of art to nontraditional settings is a conversation starter in itself – and perhaps herein lies the essence of this ever-evolving institution.

“When we present art in public places, there are many publics,” says Coates. “There are those within the art community who engage with the work within an art world context. Then there are the local audiences who live and work nearby, who engage with the work because of their connection to that place.

“Then there are those ‘publics’ who may have no interest in art, who stumble across the work or possibly aren’t even aware it is art. Because the projects are injected into public spaces they are inherently more likely than a gallery to engage a public that is not particularly looking for art.

“This can be exciting as a curator or artist, as there is the greatest risk and opportunity to change perceptions… and the place of arts and culture in our everyday lives.”

Making Art Public: 50 years of Kaldor Public Art Projects

Art Gallery of New South Wales

7 September 2019—16 February 2020

This article was originally published in the September/October 2019 print edition of Art Guide Australia.