According to the Global Carbon Project, half of all human-caused carbon emissions have been released since 1990, collapsing geological time into mere decades. Meanwhile “First Peoples have lived in deep connection with the earth’s rhythms for over 65,000 years,” writes Dr Jessica Clark in the exhibition essay for her latest exhibition at The Substation, In the air.

The sheer scale and impact of humanity’s energy production and consumption in recent history is overwhelming to comprehend. In times increasingly defined by chronic climate anxiety, it is easy to feel trapped in a state of climate doom—feeling helpless beyond the point of action.

In the air intends to cut through this paralysing discourse. Bringing together seven First Nations and non-First Nations artists, it examines the destructive realities of industry and technology wrought on Country.

This is Clark’s seventh group exhibition, reflecting her deep commitment to an intercultural curatorial practice that fosters connections between First Nations and non-First Nations artists. “I am excited by what happens when you bring artists together and share ideas—to together weave an expansive conversation between works of art from a multiplicity of perspectives,” she says. For Clark, a proud palawa/pallawah woman, conversation is integral—both as a process and an outcome. Lutruwita/Tasmanian Indigenous artist Cassie Sullivan, who has previously worked with Clark, notes that her success is due to her process of “yarning over and over again as you’re developing the work—and then the yarn comes together.”

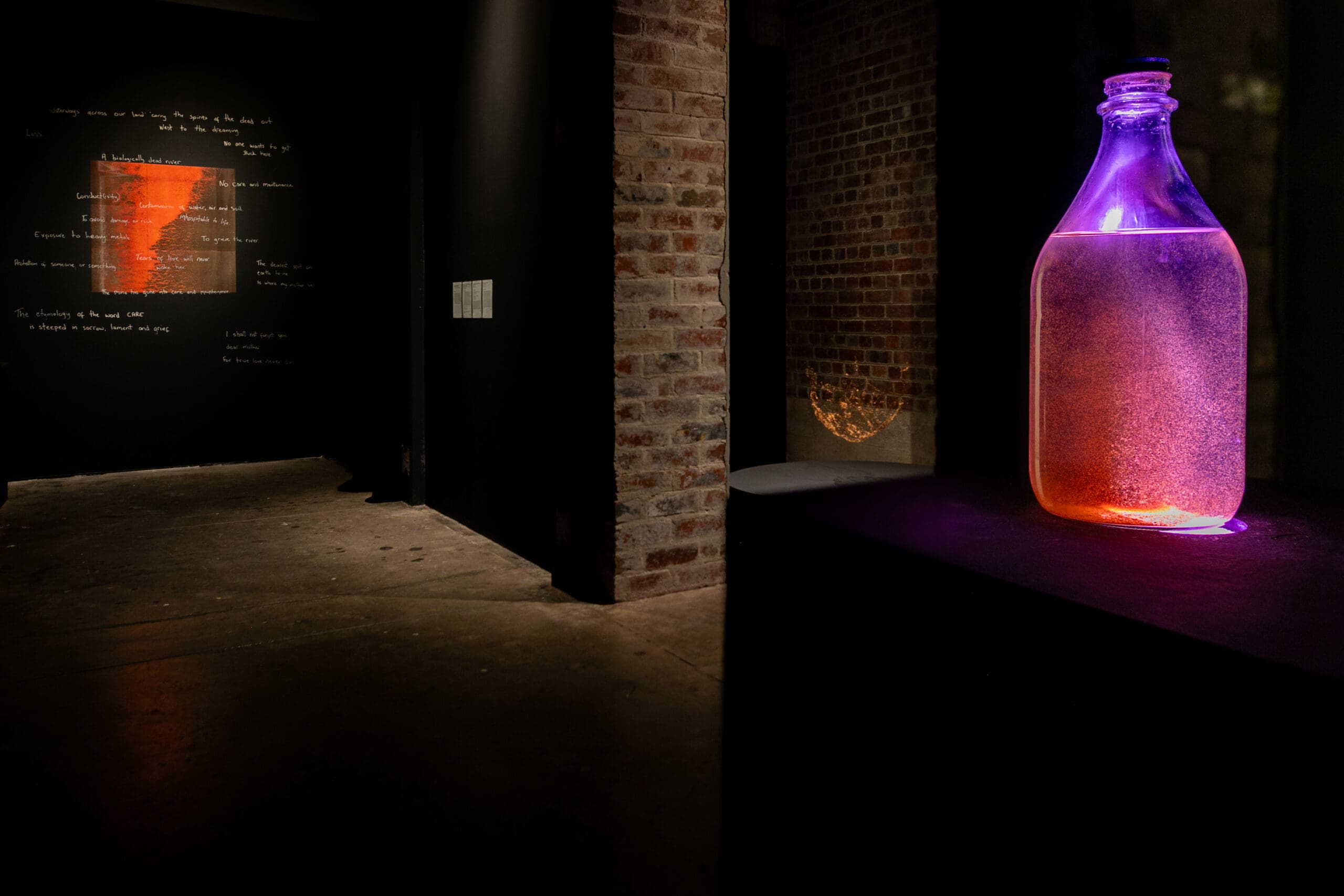

The outcome of their extended yarns is Sullivan’s sorrow for the river series which contemplates and eulogises the biologically dead Queen River in Queenstown, Tasmania. Through toxic water portraits printed on giant billboards and a jar of river water, she exposes the pollution legacy of an upstream copper mine. What took hundreds of millions of years to form was killed in 80. Sullivan critiques the casual reframing of this damage—the jar becomes a curio; the pumpkin-coloured river is now a tourist attraction.

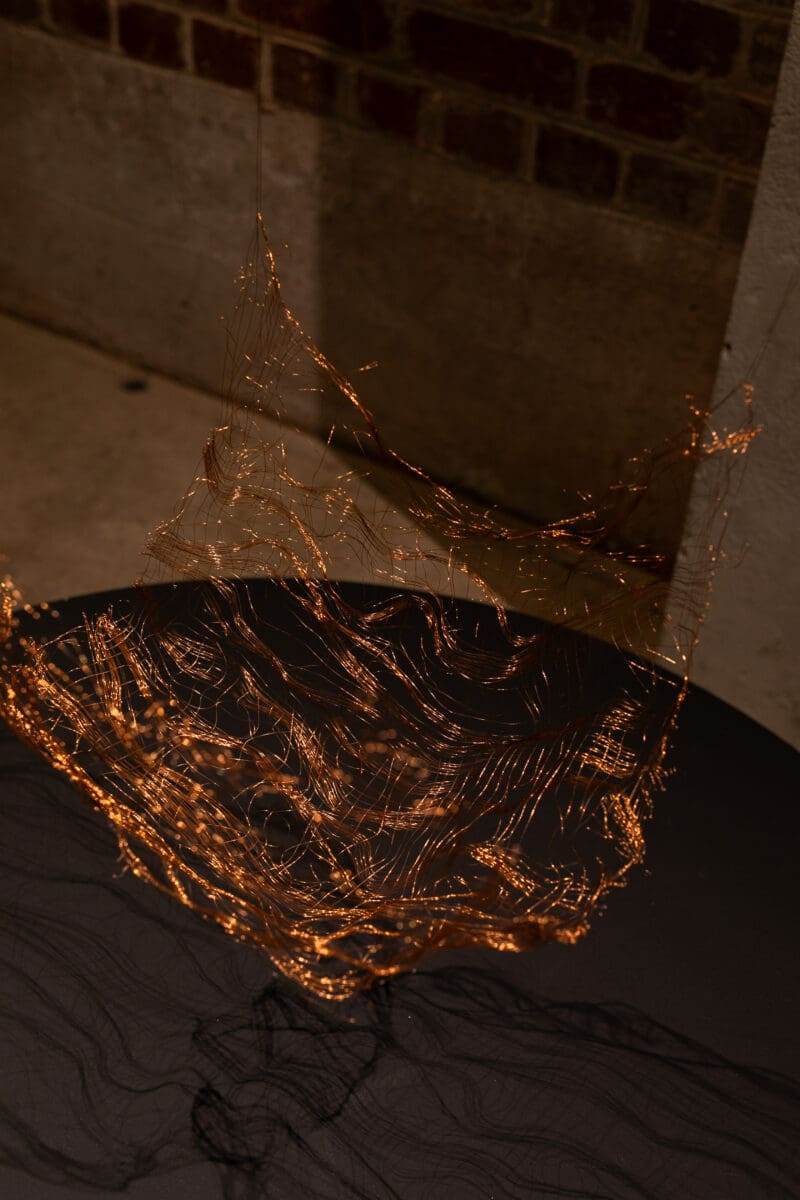

Alongside is to collect with holes in your basket i, a copper-wire vessel that engages with copper’s utility, its role in the river’s destruction, and offers a listening opportunity, having been literally passed through the waterway. Sullivan’s works prompt poignant, open-ended reflections on human activity, environmental loss, and spiritual disconnection, as she reflects: “The waterways carry our spirits when we die, straight out to the Dreaming. What happens to the spirits if the river is completely dead? They can’t move through that.”

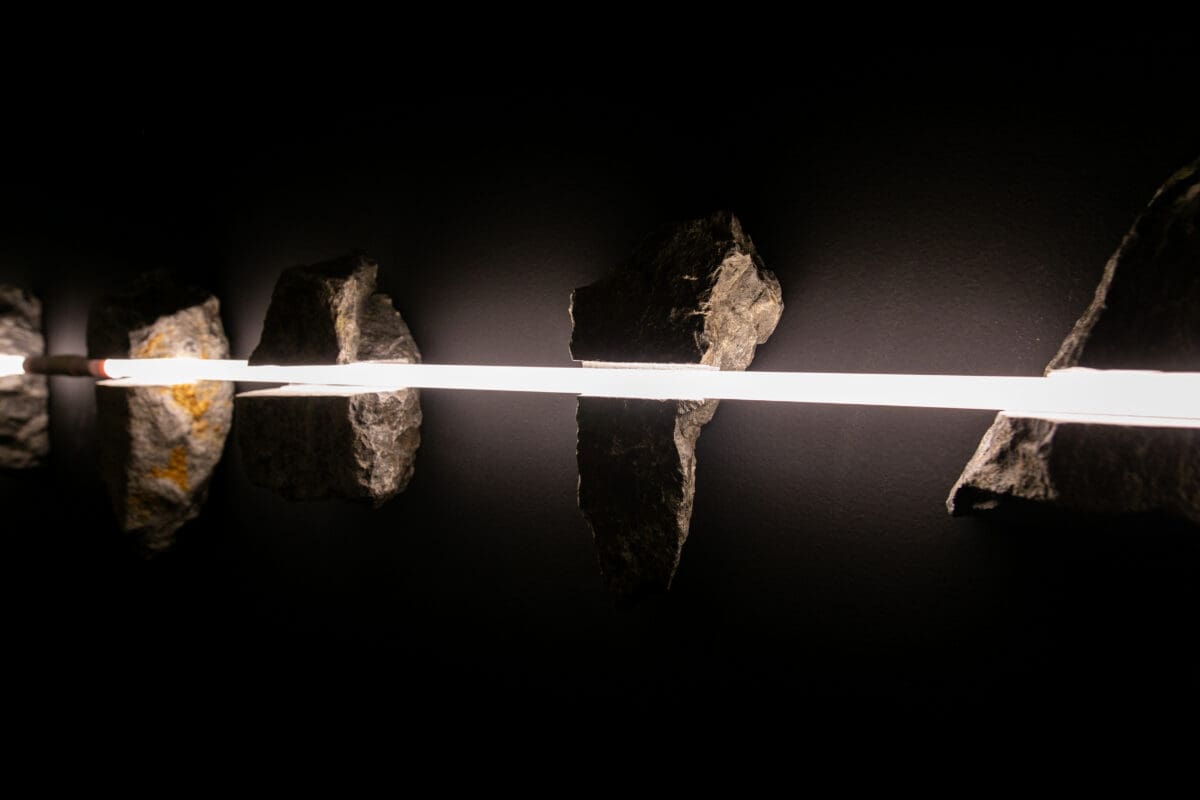

Aidan Hartshorn sculpts with the upheaval caused by hydro energy production, creating 16 Wee Jasper bluestone rocks representing the Snowy Hydro Electric Scheme dams. Once hailed as a renewable energy milestone, the project generated over 100 million tonnes of waste across Hartshorn’s ancestral Walgalu Country. His work, Bangadirra (“to cut, split, or chop”), features rocks pierced by LED light, evoking the human disruption carved into the land. Both Sullivan and Hartshorn’s works tend to the remnants of industry—acts of mourning, but also of creative defiance, as they reassert the presence of ancestral knowledge and the reflection it can offer to a wider audience.

The detritus of human activity is further explored through the lens of ecommerce in a suite of new oil paintings by Casey Jeffery. Her ability to charge two-dimensional paintings of wrapping paper with tactility and vitality is seductive, evoking the insatiable human desire for consumption. Yet this desire rests on an immense infrastructure—one that generates significant emissions through production, transportation, packaging and return shipping.

Xanthe Dobbie’s experimental desktop performance, The Long Now, exposes the egocentricity of human consumption and progress through an absurdist critique of The Clock of the Long Now—a colossal 10,000-year clock physically built inside one of Jeff Bezos’ mountains in Texas and largely funded by him. As Clark observes: “The richest 1% of the global population are responsible for more carbon emissions than the poorest 66% combined.”

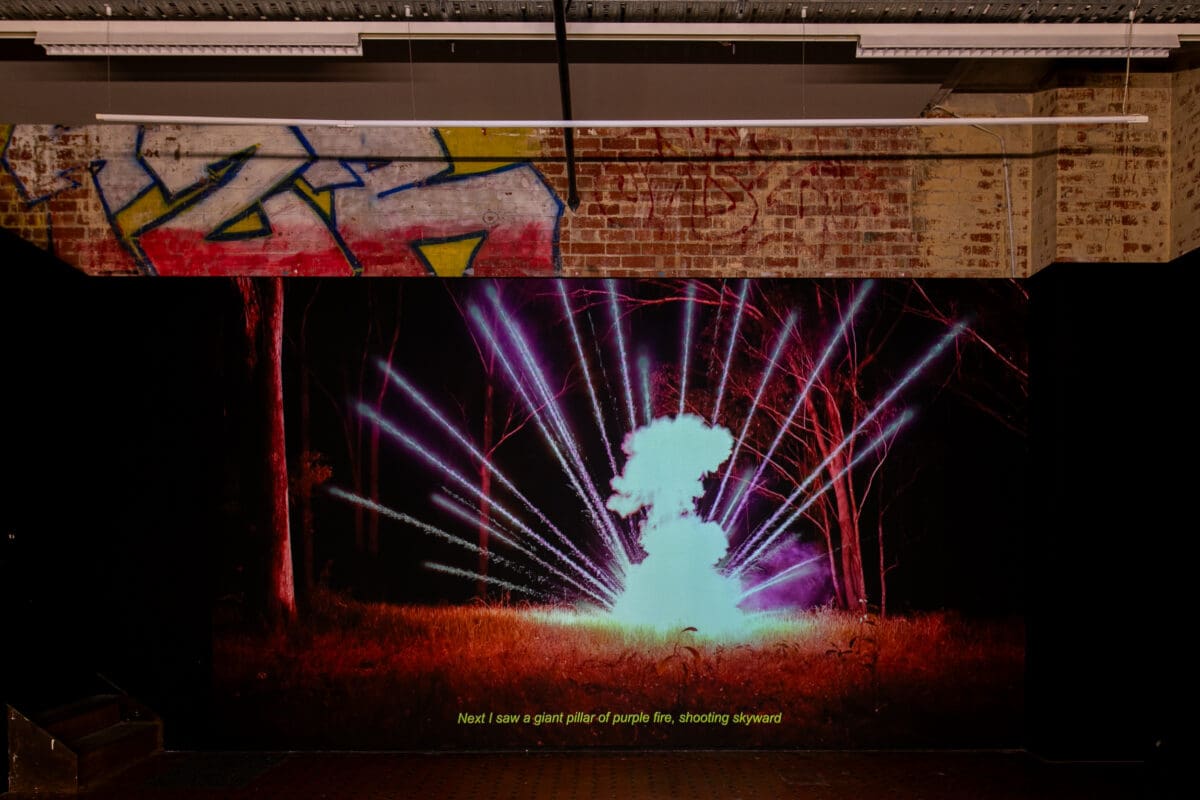

Power is a double-edged prompt throughout—the destructive power of human activity and the deep healing power of ancestral knowledge. Walpiri artist Sabrina Nungarrayi Gibson’s vibrant paintings of Kiwirrkurra’s lightning dreaming story, position First Nations wisdom at the heart of the exhibition and remind us that humans cannot be separated from Country. Emily Parsons-Lord’s mesmerising video of filmed explosions extends this tension, treating combustion as metaphor—for creation, celebration and destruction. Originating as a natural phenomenon, firepower has a strange and tortured beauty, amplified beyond necessity by humans. “Tragic poetry” is how Parsons-Lord describes the lingering fragments of light, heat, and air—an apt metaphor for the exhibition’s salvaging of human wreckage.

In The Substation—a repurposed power station, the creative act of reclamation takes on deeper resonance. Francis Carmody’s Continuous Cities I – Ferro 2024 maps a future sprouting from today’s wreckage through geological projection modelling. “The act of making is an optimistic one,” Carmody offers—a counter to helplessness and devastation.

Art offers a rare space where contradictions coexist, and where reflection can seed transformation. With In the air, Clark positions creativity not just as witness to destruction, but as a vital force for “reflection and redirection”—a collective call to imagine otherwise.

In the air

The Substation

On now—16 August