Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

Archie Moore’s works are true to life, and life, as we know, is like a box of chocolates. An exhibition by Moore is, in the words of Djon Mundine, “always special, and different.” You never know what you’re going to get. Yes, specific taxonomic themes run through his career—an interest in how personal memories are classified alongside more official histories of discrimination and injustice—but they are also undercut by phantasmal sensations. Like his childhood obsession with astral travelling, art might be Moore’s way of trying to get out of his body only to show us how bodily, visual and cognitive experience are so profoundly intertwined.

Even the most random selection of works from Moore’s back catalogue invoke worlds of mystery, despondency, anger and insight. Consider Black Dog, 2013, a doleful-looking taxidermised dog that has been painted with black shoe polish; Les Eaux D’Amoore, 2014, a line of perfume fragrances that have personal resonances such as clay, smoke and pencil; False Friends, 2014, a video of purposefully mistranslated foreign speech with British Carry On-style innuendo; United Neytions, 2014–17, a series of 28 carefully designed flags based, perversely, on a piecemeal anthropological mapping of traditional Aboriginal communities; and Bogeyman, 2017, a Sasquatch-sized wooden stick-figure with a stiff white sheet draped over it, like a lumbering ghost. Moore is incomparable as an artist—he’s one of Australia’s greats—but if you had to relativise him, Mike Kelley by way of Jimmie Durham wouldn’t be a bad place to start.

Currently on display at Gertrude Contemporary is what Moore refers to as his “house show.” The ambitious exhibition, Dwelling (Victorian Issue), builds upon a 2018 project at Griffith University Art Museum, Archie Moore: 1970-2018, bringing together an assemblage of ‘memory rooms’: simulated hauntological living spaces.

Like manifestations of intergenerational trauma, the materials in Moore’s exhibition—classroom desks, a vinyl couch, the smell of Dettol—communicate across seemingly vast distances, invoking uncanny Mike Nelson and Gregor Schneider vibes only with more pressing questions about race and class. Dabbling in psychogeography, the artist immerses viewers sensorially but without ever renouncing a socio-political conscience.

An idiosyncratic guiding metaphor throughout the exhibition is the camera obscura—Latin for ‘dark room’. The show is about the light we let in; the illusions and inversions linking memory to self-formation. Unlike his Millennial and Xennial contemporaries, Moore, a Gen Xer who turned 52 this year, doesn’t so much affirm an identity in his work as deal suspiciously with why it always gets in the way.

Moore loves words, and so the distinguishing connotations between ‘dwelling’, ‘room’, ‘home’, ‘hut’, and ‘house’ are motivating factors in these mise-en-scène adventures. It is certainly true of perhaps my favourite work of his, the magical-realist A Home Away From Home (Bennelong/Vera’s Hut), from 2016. This is an imagined version of Woollarawarre Bennelong’s house (originally built in 1790) that Moore temporarily erected behind the Sydney Opera House for the 20th Biennale of Sydney. The work considers the first ever residential building constructed by a white person for a black person in Australia, however, its interior emulates a childhood memory of the bleak living conditions of his (possibly) Kamilaroi grandmother, Vera. She, like many First Nations people, suffered through the country’s eradication, intimidation, dispersion and assimilation strategies.

Dwelling (Victorian Issue) is based, in part, on Moore’s experiences growing up poor in a mixed-race family in the small Queensland town of Tara, 200 kilometres west of Toowoomba. There, racial antagonisms, both inside and outside the family, instilled in him a wish to be invisible. In the early 1990s Moore left Tara for Brisbane, where he lived for almost three decades before moving recently to Lamb Island (Ngudooroo), a quiet, one-by-two-kilometre island in the Moreton Bay region of South East Queensland. “I want to do some experiments with the red earth here on the island, as a medium,” he tells me. “I’ve been collecting what I find in the backyard when I dig—artefacts from the previous owners.”

Moore’s own ancestral excavations have unlocked a lot of mixed emotions over the years: “I’ve read newspaper articles of a great-uncle being murdered by his son at a camp and most likely my grandfather was there to witness that, which might explain some of his violent behaviour,” says Moore. “All my uncles and aunties lived vast distances from their parents—very dislocated—and had trauma that was kept hidden. My (white) father also told me a story about his father beating him until he exhausted himself. When I think about where my mother and father came from, it’s no surprise they met.”

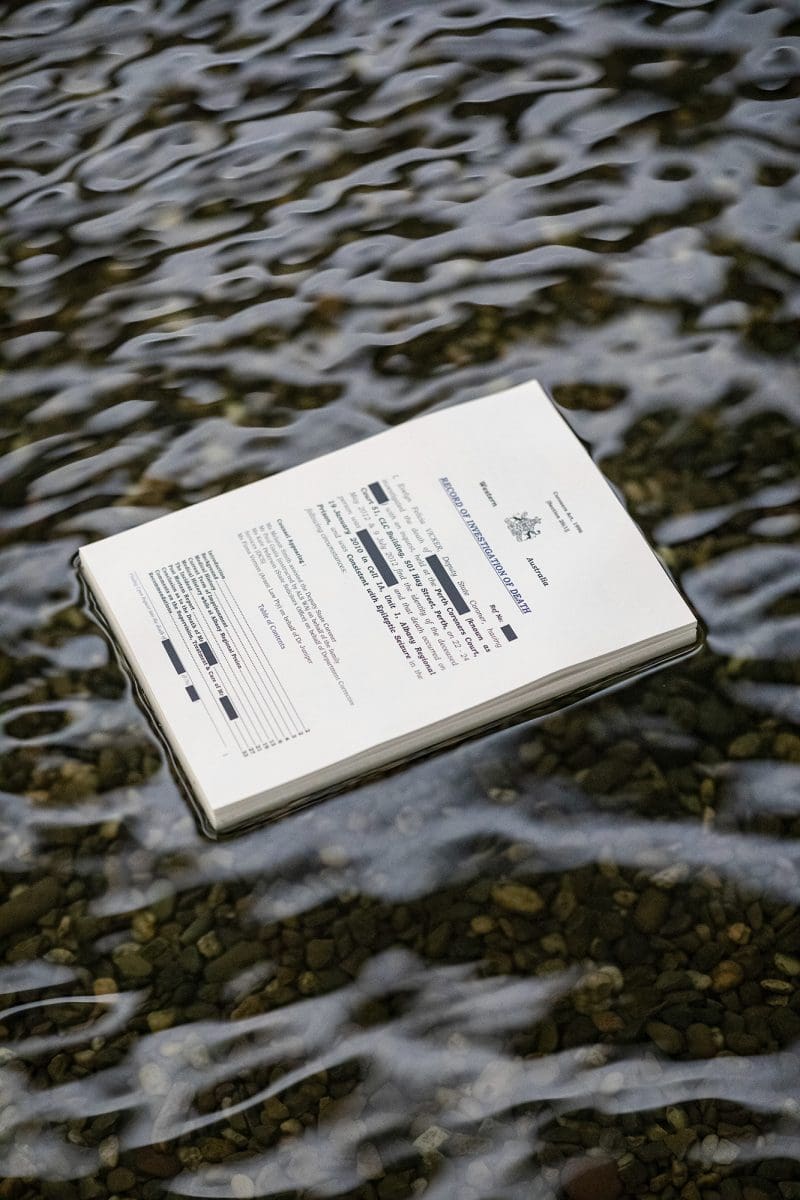

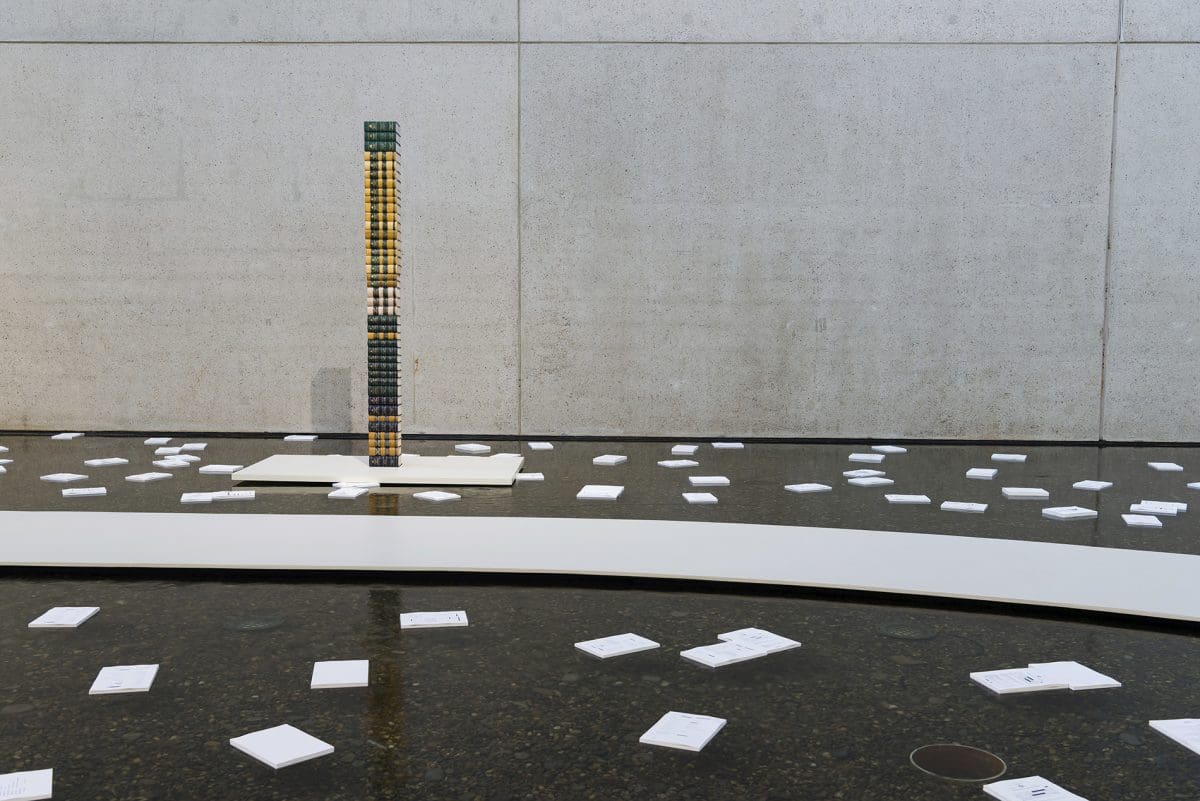

Increasingly motivated to speak back to present-day inequalities, Moore’s work,Inert State,2022, currently on display in Embodied Knowledge at the Queensland Art Gallery, addresses Aboriginal deaths in custody. It comprises numerous pages of state coroner’s reports floating in the Gallery’s interior water feature adjacent to stacks of leather-bound transcripts of parliamentary proceedings. Against the exhibition’s title, Moore’s work, here, feels curiously disembodied, as if the locus of its dismal political reality cannot possibly be represented. It’s another example of how, when it comes to issues of institutionalised injustice, Moore’s default position is to first consider the ghosts.

Dwelling (Victorian Issue)

Archie Moore

Gertrude Contemporary

27 August—23 October

Disembodied Knowledge: Queensland Contemporary Art

Queensland Art Gallery

13 August—22 January 2023