When the news broke that Archie Moore’s kith and kin won the Golden Lion for Best National Participation at La Biennale di Venezia 2024, it was historic not just for Aboriginal art but for so-called Australia. This exhibition, arguably the most prestigious award in the art world, will be remembered as a turning point. Seeing the news of Archie’s win shared widely on social media by Blackfullas in the arts and beyond, was heart-warming for our communities. Reading Archie’s acceptance speech represented a moment of profound recognition. “Aboriginal kinship systems include all living things from the environment in a larger network of relatedness, the land itself can be a mentor or a parent to a child,” he says. “We are all one and share a responsibility of care to all living things now and into the future.” His words made our people feel heard.

To speak about the importance of kinship on such an international stage is monumental, especially after the pain our communities endured with the failed referendum and its aftermath. In Native Title is Not Land Rights! a 2023 book by Common Room Editions, Gumbaynggirr activist, academic and writer Professor Gary Foley, writes that, “History would be a wonderful thing, if only it were true.” His words have resonated with me. I’m struck, in particular, by the way that Archie investigates through his research how the real history of this country has been obscured, unveiling it through his practice. Professor Foley reminds me of the immense power that Aboriginal artists and activists hold, channelling truth through material and memory.

Archie’s earlier works, United Neytions (2018), permanently displayed at Sydney Airport’s International Terminal, is a pivotal example of how his practice challenges misconceptions of national identity. This series of 28 flags critiques anthropologist R.H. Mathews’ inaccurate map, which falsely suggested that there were only 28 Aboriginal nations. This work weaves a narrative that confronts the false histories written by those in power. Euahleyai/Gamillaroi legal academic, writer, filmmaker and advocate Larissa Behrendt AO states that United Neytions provokes questions about our relationships to national identity and how we represent ourselves. This relates, more specifically, to the way tourism propels this at an international level. kith and kin builds on these ideas, expanding them in scope and audience.

“The work is both deeply personal and intensely political, reminding us of the ongoing fight for justice. It sets a precedent in global art for the ways we can collectively, as a nation, move forward in truth which honours our kinship systems.”

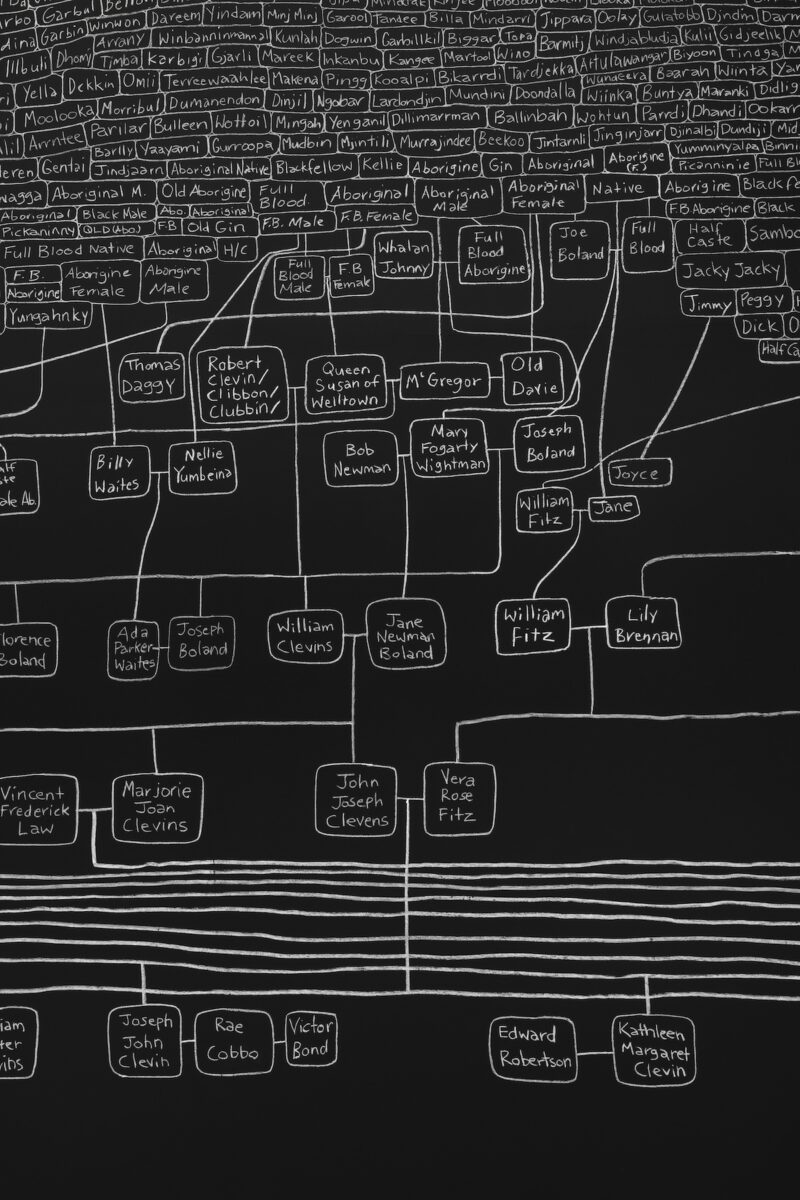

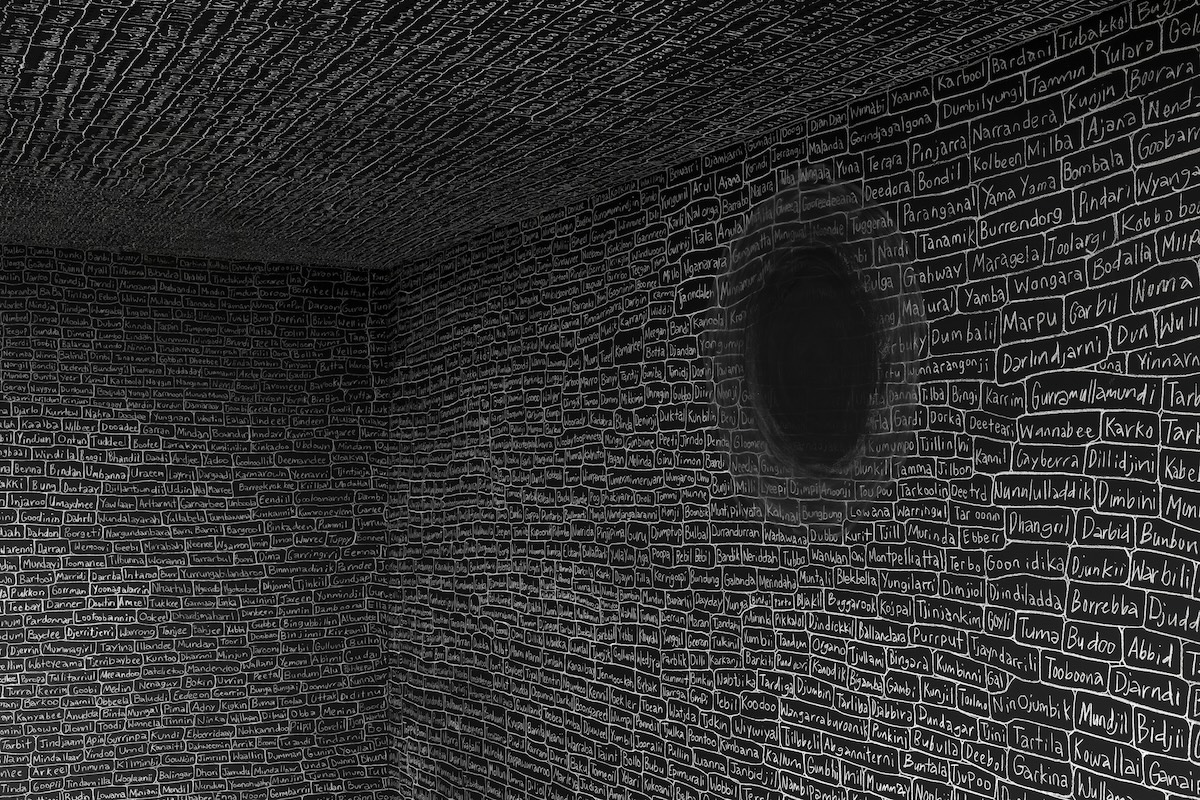

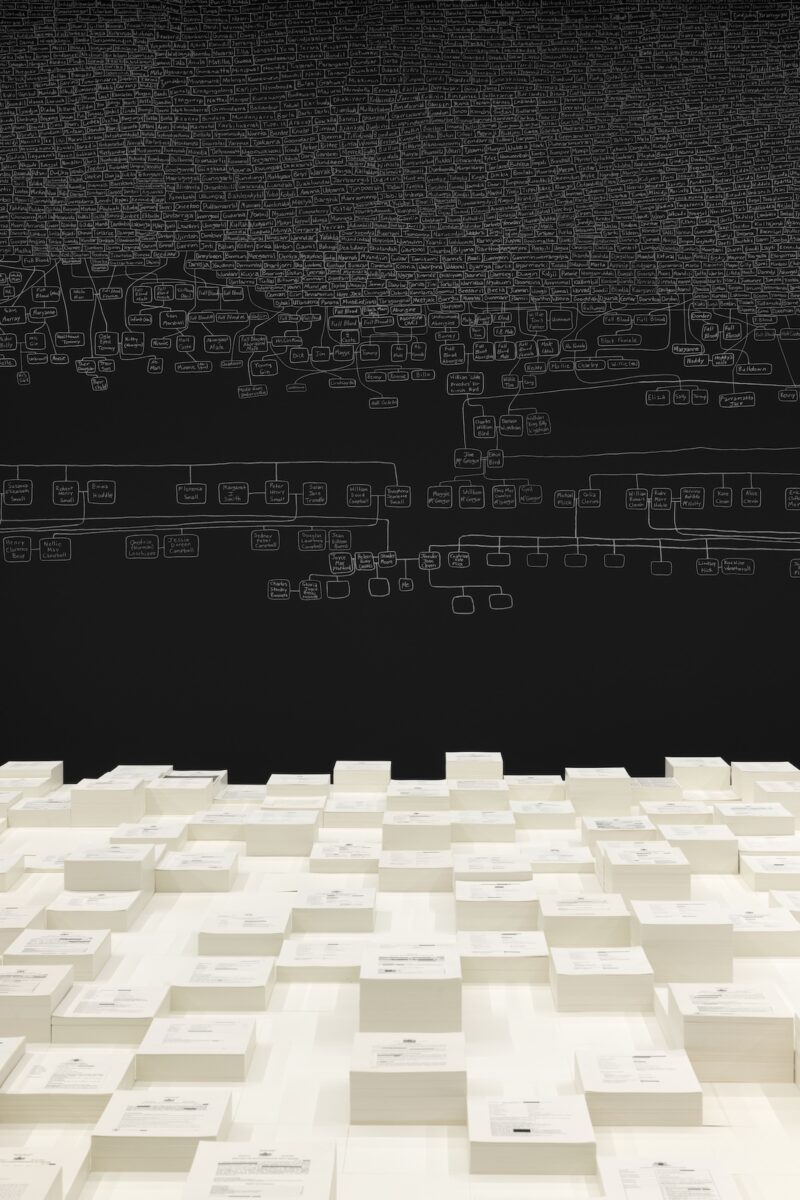

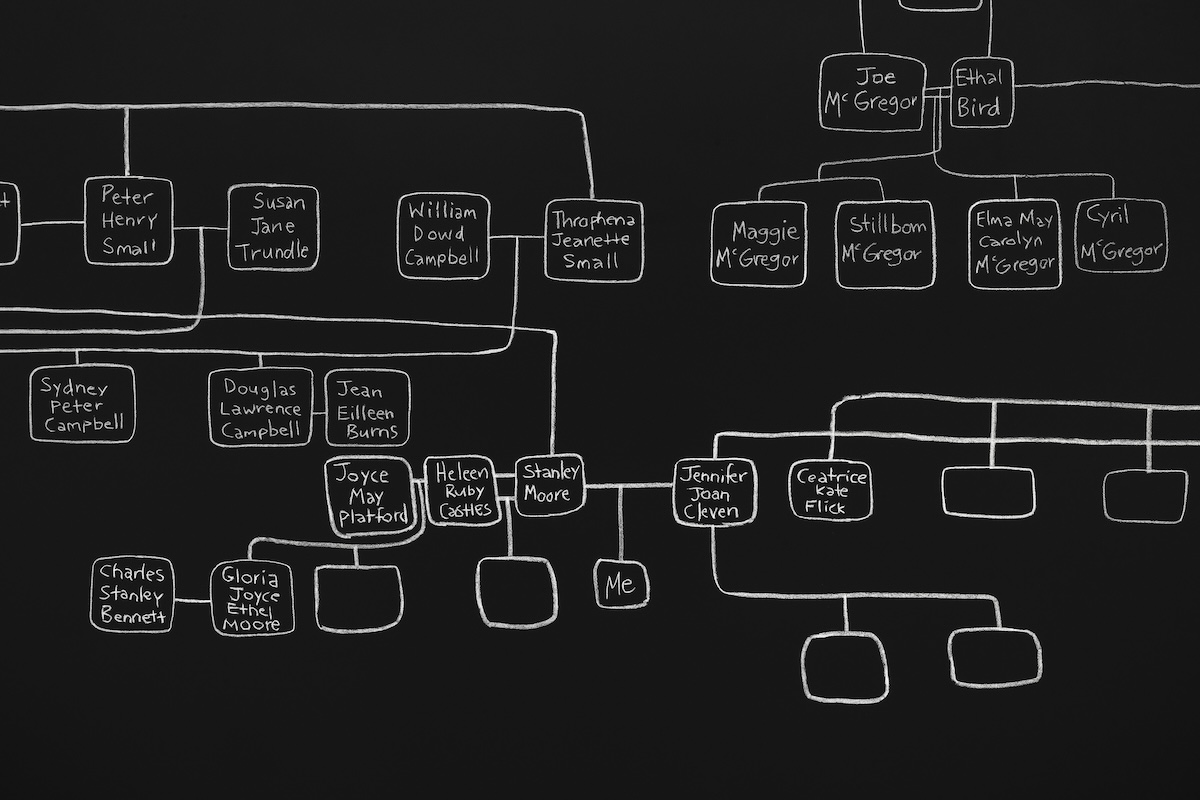

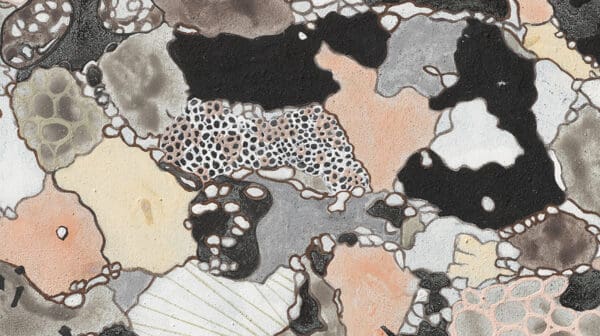

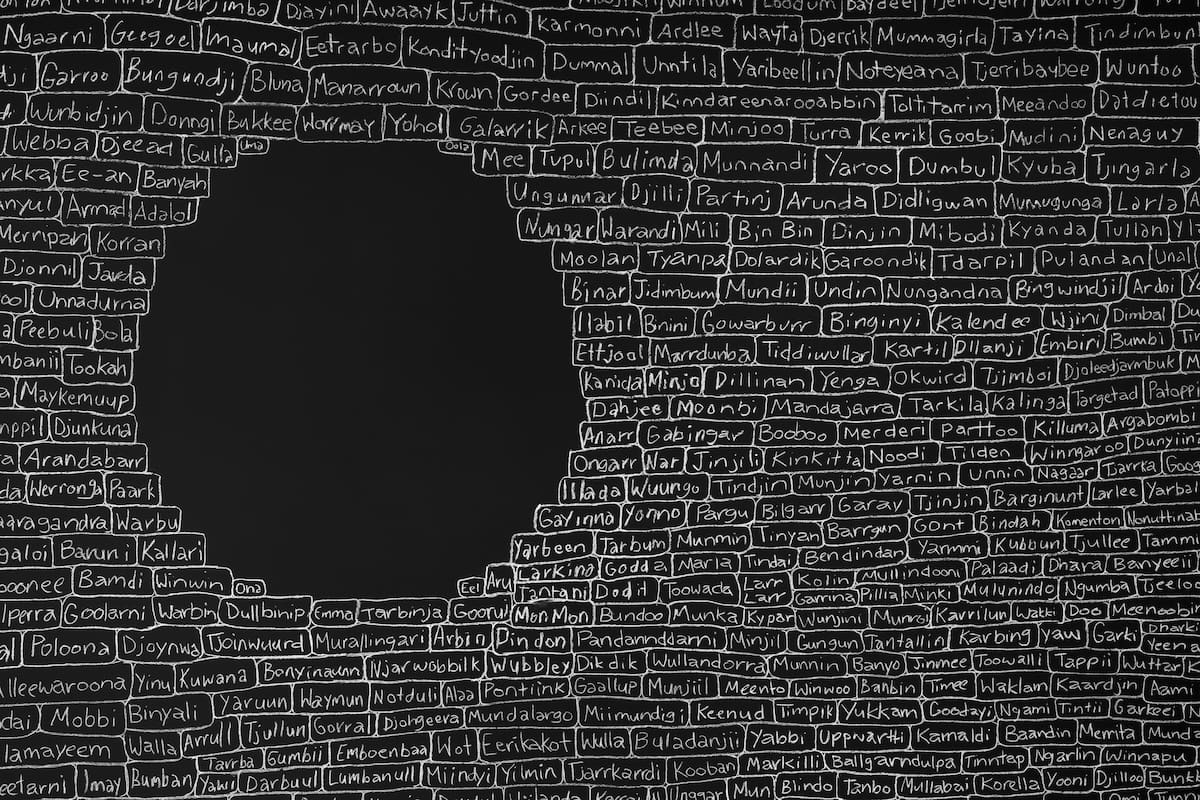

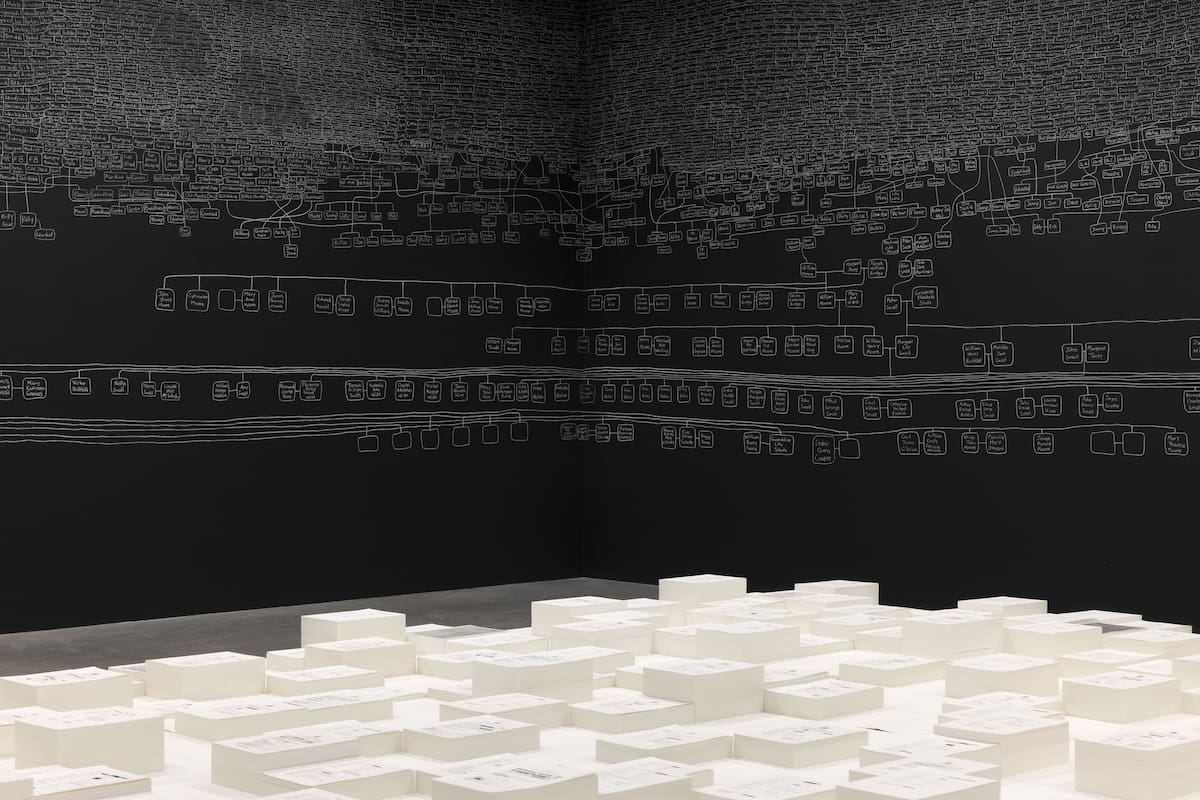

kith and kin presents a hand-drawn familial tree in white chalk across black chalkboard walls and the ceiling. At the room’s centre are rows of redacted coronial inquests detailing the deaths of 557 Aboriginal people murdered in custody since 1991, each document displayed at various heights. A shallow pool of water surrounds these papers, reflecting the kinship tree above. kith and kin is a ground-breaking and deeply-felt reflection on the racism that still occurs today. The installation encapsulates the power of art to convey stories of survival, grief, and resistance.

This powerful and heart-wrenching image connects Archie’s ancestors, family, and kin who have perished at the hands of colonial violence. The work is both deeply personal and intensely political, reminding us of the ongoing fight for justice. It sets a precedent in global art for the ways we can collectively, as a nation, move forward in truth which honours our kinship systems.

This is also the first time an Aboriginal artist—or any Australian—has won this accolade. Archie’s long-spanning career has been defined by research-based representations of personal identity, national histories and the structures of racism. He addresses these complex concepts by recreating his childhood memories, creating rooms of the significant moments in his young life. Archie’s practice sparks a conversation between archival and family research in speaking to policies and injustices.

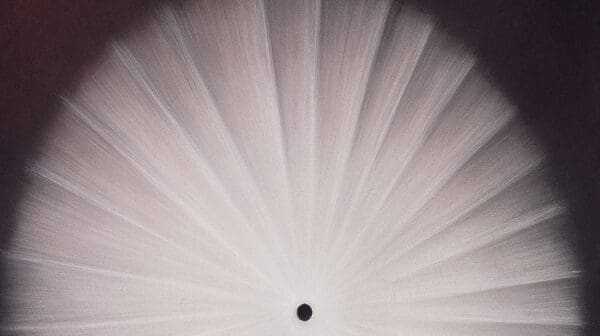

Dwelling (Victorian Issue), which was shown at Gertrude Contemporary in 2022, explores these ideas through an immersive installation. In a 2022 conversation with Paris Lettau, Moore describes the work as “a kind of metaphor for the failure of reconciliation…and more so personally, the failure of others to understand me.” This series will expand, in its seventh iteration, into a new moving image work presented at the Samstag Museum of Art as part of this year’s Adelaide Film Festival. This version of Dwelling, like kith and kin, will speak to memory and the ongoing effects of colonisation, as a vessel of truth-telling, family stories and healing.

As a young Aboriginal woman emerging in my own practice, writing this reflection feels daunting as I’ve admired Archie since art school. However, there’s a common thread between myself, Archie and every single Blackfulla. As Kombumerri and Wakka Wakka academic and author Dr Mary Graham writes in a 2008 article in the Australian Humanities Review: “The two most important kinds of relationship in life are, firstly, those between land and people and, secondly, those amongst people themselves, the second being always contingent upon the first. The land, and how we treat it, is what determines our human-ness.” Meaning the common thread between Aboriginal people is our relationship with the land, and therefore, with one another. This connects to the everyday resistance that we all experience. kith and kin offers a raw insight into identity, truth, and the legacies of colonial violence. The time Archie spent drawing this kinship tree and stacking the 557 piles of inquests, is testament to the way that he has carved out space to speak to injustice and the way our people persevere in shifting narratives.

His practice, creativity and vision allow us to glimpse the horizon of common ground. kith and kin creates dialogue and space that enables our communities to envision a world where our existence is acknowledged. He asks us all to confront the past and the present in the hope of forging a pathway where our storytelling isn’t written on the wall but upheld with care and respect for future generations.

kith and kin

Archie Moore

QAGOMA

27 Sep 2025 – 18 Oct 2026

This article was originally published in the November/December 2024 print issue of Art Guide Australia.