Brisbane-based Indigenous artist Archie Moore, who will represent Australia at the Venice Biennale in 2024, will call on family history—“something I avoided and was wary of going there”—as “one component” of the project.

Toowoomba-born, Moore is known for installations that play with his memories of interior spaces, from his childhood home to school to church to his grandmother’s hut. He also recreated the home of Woollarawarre Bennelong, the “first public housing for an Aboriginal person”, made in 1790 and which had a dirt floor.

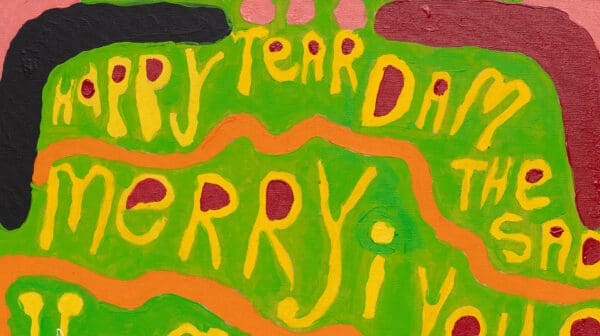

His art delves into, as he says, “false memories, things that have been told to me”. Moore’s previous work has included the 2017 series United Neytions, creating “false flags” from the 28 Aboriginal nations that white, amateur anthropologist R. H. Mathews named in 1900. And in 2015 he presented Blood Fraction, which consisted of 100 self-portraits ranging from “full blood” to “hectoroon”, with finely graded skin colour and facial features.

Moore previously told this journalist for an exhibition catalogue in 2018: “Non-Indigenous people will identify Aboriginal people by skin colour but Aboriginal people do so by relationships. …I’m too pale to be Aboriginal for some non-Indigenous people and also not black enough for some Aboriginal people. I don’t know where I sit…”

In the past, an Auntie has disputed Moore’s designation of Kamilaroi as his clan, and others say the family’s language is from a neighbouring nation. In Sydney this week, when the Australia Council for the Arts announced Moore’s commission for the Venice Biennale, Moore said he had spent three years delving into family history.

The research confirmed Moore is from the Bigambul people, from the Western Downs and Goondiwindi areas of Queensland: “I’ve been putting that research into artworks, into a visual form. I did a large family tree—the idea was to take it back 60,000 years. Lots of little branches and people coming off it.”

In his research, Moore uncovered documents showing his forebears were forced to flee and forbidden from exercising their own free will. “My grandparents were pursued by police across borders, back and forth and from town to town. They weren’t allowed to associate with other Aboriginal people, and they had to seek permission from the Protector of Aborigines to marry.”

Moore’s research goes back to “my great-great grandparents on my Aboriginal side”. He found his maternal great-great grandmother was presented with a breast plate that named her as “Queen Susan of Welltown”, the name of a sheep-shearing property, by a white pastoralist in Bungunya in Goondiwindi, Queensland.

“There’s royalty in my family,” he says. “I think it was sarcastic. It’s not so common with Aboriginal women, but Aboriginal men [were given breast plates with] the title of ‘king’, the chief of the clan or whatever.”

Moore grew up in the tiny town of Tara, 171 kilometres northwest of Toowoomba, and spent a lot of time at home, reading books and drawing. His work Dwelling, 2010, was a recreation of his childhood home, where an audience could walk through the domestic spaces, view the popular shows of that era on the TV, and sift through Moore’s collection of old drawings, cartoons, magazines, and books.

This and other works were “about the impossibility of having a shared experience with another—the idea that two people or two groups can never fully understand one another… But there’s a kind of paradox, too: I can never be certain that others haven’t had the exact same thoughts and feelings as me.”

The exact details of Moore’s Venice Biennale project remain under wraps until early 2024, but his commissioning is significant in terms of representation, as only the second solo First Nations artist commissioned by Australia for the Venice Biennale (the first was Tracey Moffatt in 2017).

The curator of Australia’s participation at the Venice Biennale, Ellie Buttrose, said there had previously also been “important group shows” of Indigenous artists at Venice.

As the curator of contemporary Australian art at the Queensland Art Gallery / Gallery of Modern Art [QAGOMA], Buttrose has worked with Moore before, describing his approach as “generous” in shining a light on his personal histories as well as the impact of colonisation.

Meanwhile, in June this year, Moore will have an exhibition at the Cairns Art Gallery, using the architecture of the old courthouse and four interior doric columns to question for whom the four pillars of democracy are intended.

In this installation, Moore will employ the corrugated iron Aboriginal people have used to make homes. He will also include photographs of police engaged to protect so-called democratic pillars. For example, when the National Guard was deployed in a “big show of force” outside the Lincoln Memorial during the Black Lives Matters protests, or police protecting a Captain James Cook statue in Sydney.

When asked at the Australia Council launch about his thoughts on the pending Voice to Parliament referendum, Moore said: “We’re just going to talk about my art practice; we’ll leave that one alone if we can.” Yet sovereignty will run through his work at Venice, he agreed.

The Venice Biennale will run between 20 April and 24 November 2024.