Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

In March last year Tom Nicholson, Caroline Rothwell and Brook Andrew were taken around all the museums in Cambridge.

In centuries-old English institutions they found themselves with now-extinct Australian animal skulls and indigenous spears. There were Galapagos Islands plants collected by Charles Darwin, a New Zealand shell picked up by James Cook and the first-ever European drawing of a kangaroo.

It was a bit of a time warp. And knowing what we do about the brutality that occurred when Europeans started to make their way around the Pacific, it was also pretty confronting.

“It raised all sorts of questions about how the material was collected and what it really represents.” says Australian Print Workshop director Anne Virgo, who visited the museums too. “Nothing was necessarily as it seemed.”

Virgo is speaking at the 35-year-old print workshop about its latest foray overseas, a project that began with the research trip to Cambridge and culminates with a solo shows of prints by each artist in Melbourne in April, May and June and a group exhibition in Cambridge this European summer.

Virgo and Nicholas Thomas, the director of the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, forged the international partnership as a way of bringing Australian artists into contact with what Virgo calls the “rich trove of Australian history hidden in the MAA vaults”. Given that many of the earliest European drawings ever made in Australia were produced as prints and that there was a printing press on the First Fleet, Virgo sees a sense of synchronicity in the project.

Nicholson, Rothwell, Andrew, Virgo and APW senior printer Martin King saw many early Australian prints – depicting Indigenous people, landscapes, animals and wildflowers – in the two weeks they spent in Cambridge. At the Museum of Zoology they also saw the Galapagos Islands finches that helped Charles Darwin develop his theory of natural selection; at the Fitzwilliam Museum they found first editions of Cook’s voyage books. They looked at botanical samples at the herbarium and, in the Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology, a proclamation board once nailed to a tree in Tasmania.

“It was like a giant fishing net capturing a whole lot of stuff,” says Nicholson of the back-to-back museum visits.

“There were lots of extraordinary things: some were simply great and others began to gestate and become the starting points for thoughts or works.”

The starting-point proper for Nicholson’s April exhibition – the first of the APW solo shows – turned out not to be stored in Cambridge at all but in a naval archive 222 kilometres south, in the coastal city of Portsmouth. It was a drawing and to see it Nicholson had to pass a series of military checkpoints and then stand on a chair to view it from above.

The drawing is by John Webber, an English artist who accompanied James Cook on his third voyage around the Pacific in the 1770s, and is what Nicholson describes as the “earliest surviving, probably first European” image of contact between Europeans and Aboriginals. Too large and fragile to be displayed upright, you can only ever view it laid across a table.

Even then, it poses as many questions as it answers. Of all the drawings Webber made on that trip, it was the only one not turned into a published engraving and the only one not to end up in the British Museum. Yet, Nicholson says, Webber “invested a huge amount of time in it.”

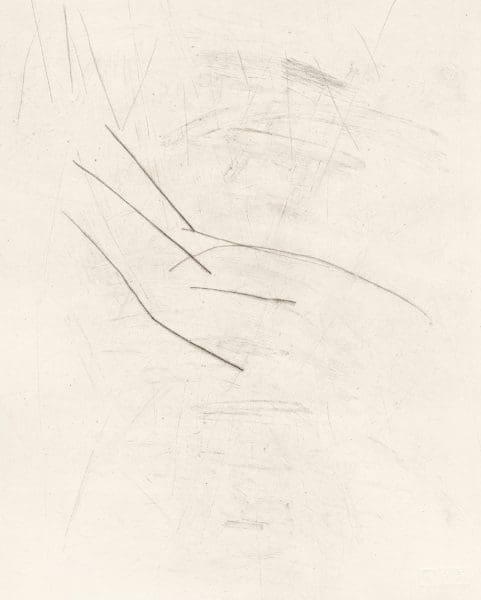

Some parts of the drawing, which is titled Captain Cook’s Interview with Natives in Adventure Bay, Van Diemen’s Land, 29 January 1777, are extremely worked up and others almost ghostly in their vagueness. Where other artists produced slightly awkward works when encountering things they had never seen before, Webber’s drawing seems more contrived and less of the moment. Several of his Indigenous figures adopt what Nicholson calls the “classical poses of art school”.

“It was too big to have been made on a beach in Australia and it feels like it was already tracking to be an historical painting that would make Webber famous in London,” Nicholson says. “The exception to that, and which my whole body of work is about, is the designation of scarification in the drawing. That was something he observed and couldn’t assimilate in what he knew of the world.”

Webber’s scarification lines are on the shoulders and torsos of some of the Indigenous men that Webber drew meeting Cook on a rugged coastline in Tasmania. While some of these lines fall into a grey zone between what might be deliberate cut marks and what might signify the human anatomy, others more clearly suggest the body modification that Nicholson had seen in other early Australian drawings.

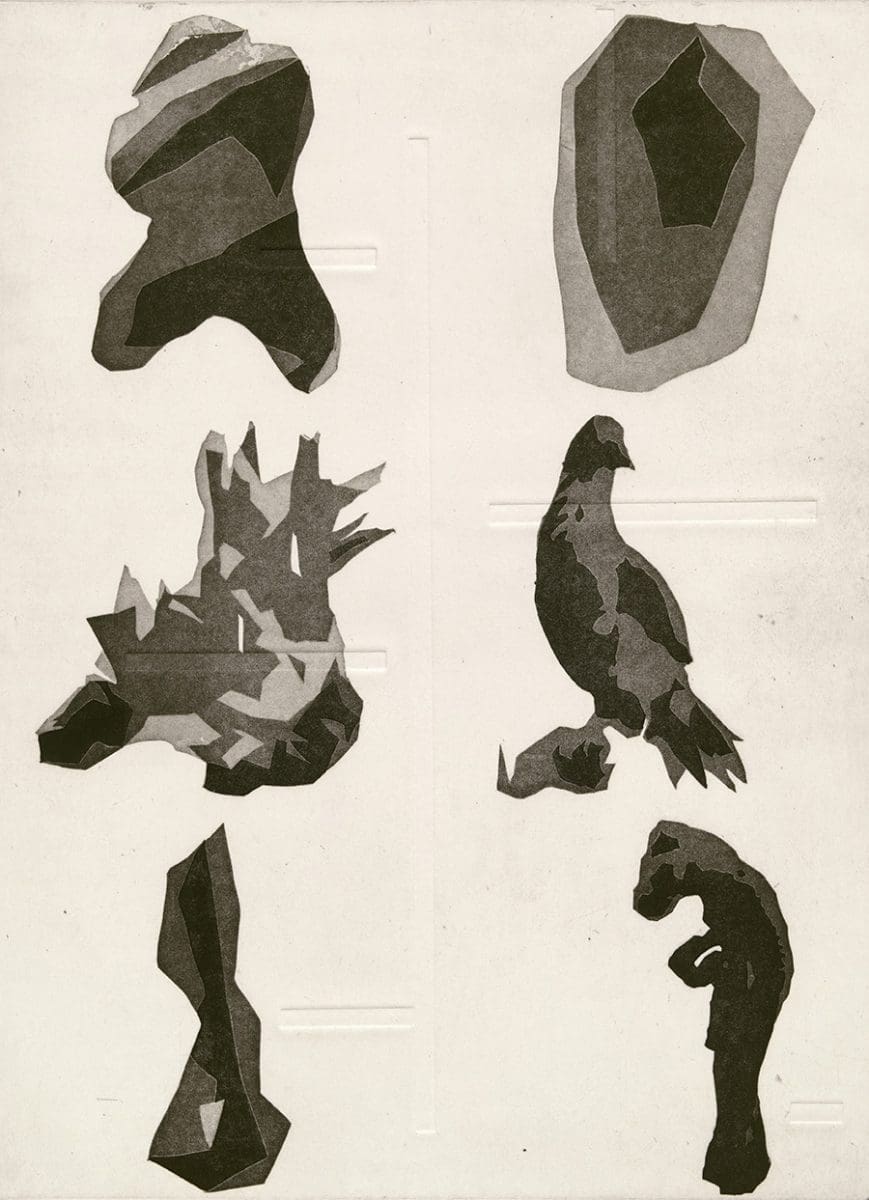

Taking no more than 10 of Webber’s lines as his starting point, Nicholson has made 24 (the number of Indigenous Webber depicted) supremely reduced dry point etchings. Each print evokes “the lines that could be scars” on Webber’s drawing. On the one hand these are minimalist graphic abstractions but on the other they are strongly suggestive of human flesh being cut with a sharp object. There are subtle burrs along the edges of some marks that evoke the texture of scar tissue.

“It’s a visual idea that partly began from the Aboriginal spears in Cambridge and what it was to imagine them as the point of contact and also from the proclamation board that was made with a perforated drawing and was very marked from its life,” he says.

It has continued with Nicholson making two trips to the Bruny Island beach where Webber set his drawing and where Nicholson says he was shocked to find many of the landscape elements just as Webber depicted them. Nicholson has also started discussing the work with historian Greg Lehman, one of the few other Australians to have seen it in Portsmouth. The content of some of their conversations is to be transcribed for the exhibition.

But even after this show Nicholson suspects he might continue with Webber and co. Just as Virgo describes the UK research trip as “a trigger”, Nicholson says, “It feels like this exhibition isn’t the end of it.”

Tom Nicholson

Australian Print Workshop

2 April—30 April

Caroline Rothwell

Australian Print Workshop

7 May – 4 June

Brook Andrew

Australian Print Workshop

11 June – 9 July