Making Space at the Table

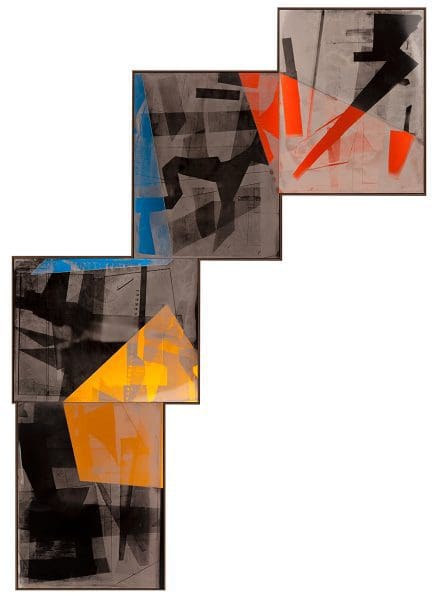

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

Cameraless photography has garnered an unusual amount of public attention in the past year. In July, Sydney artist Justine Varga won the Olive Cotton Award for photographic portraiture with her work Maternal Line (2017): a piece of film was marked by the artist’s grandmother with spit and scribbles, then developed and printed by Varga in the darkroom. It’s a beautiful, subtle image, with glowing lines on a field of deep green and purple.

The decision to award Varga the $20,000 prize was met with what judge Shaune Lakin described as “a disproportionate level of criticism” – reported widely in the mainstream press, as well as attracting vigorous social media commentary. Photographers, artists and members of the public questioned whether Maternal Line ‘counted’ as a true portrait – or even a true photograph, since it didn’t use a camera.

“To argue that photography requires a camera,” wrote Lakin in response to this debate, “is to assert a very partial or selective view of the medium’s history and its contemporary iterations – one that favours the idea of photography as technological observation rather than an embodied process.”

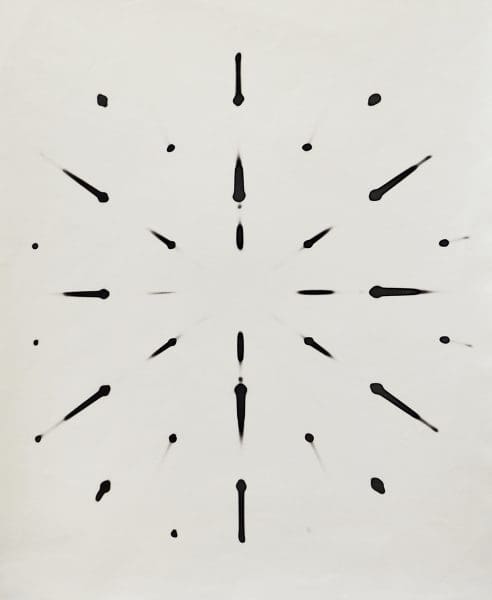

Featuring over 30 artists, works range from the 1930s to recent months, and span processes ranging from early chemical- based techniques to images produced with photocopiers and scanners. There isn’t a camera to be seen. “The interesting thing about cameraless photography for me is that it does really pare back the medium,” says Monash Gallery of Art curator Stella Loftus-Hills. “You’re really going to the essentials of what photography is. Cameraless photographs are often about light and time – and often really self-reflexive in the sense that a lot of them are essentially about photography.”

Photography has a rich history outside of the camera. The earliest processes involved simple plates or paper coated with chemicals, exposed to light. And even with the invention of the camera, photographers continued to experiment with cyanotypes, tintypes, lumen prints, photograms – all produced without a lens, and often with many hours of darkroom experimentation that can be all too easily discounted from the photographic process.

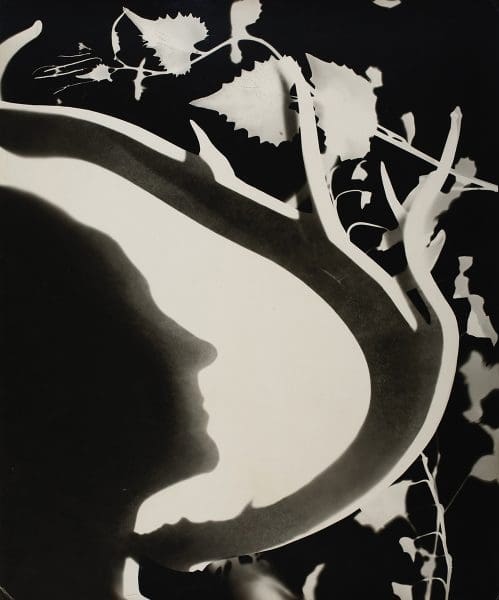

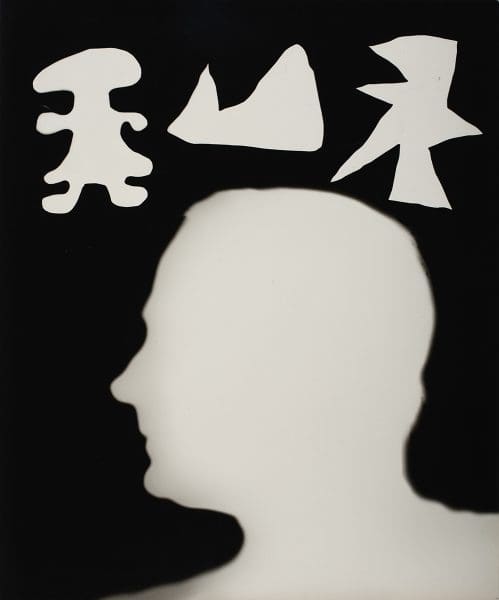

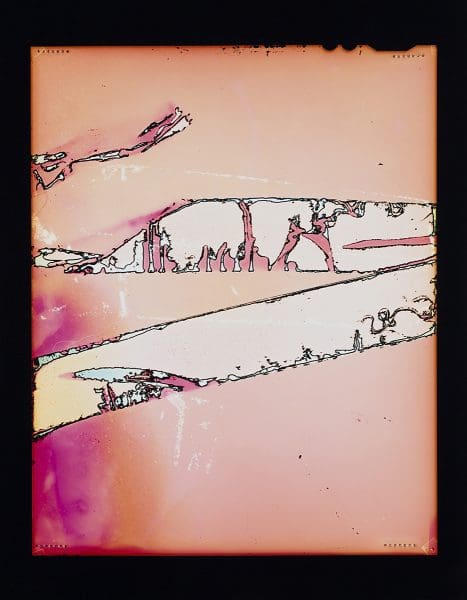

Key works in Antipodean Emanations include a 1947 series of photogram portraits by New Zealand artist Len Lye, whose subjects included Georgia O’Keeffe and Joan Miró. Using the photogram process developed by Man Ray, Lye asked his subjects to lay their head on a piece of photographic paper in a dark room; the light was switched on and off, producing a silhouette once the paper was developed. Like many of the exhibition’s works, these are unique objects rather than easily-reproducible prints we associate with the medium.In Justine Varga’s Memoire series (2016), the film itself is the subject: exposed to the elements, scratched and marked. Similarly, Robert Owens’ 2009 series Endings is produced from the discarded ends of old film rolls; developed and printed, they transform into luminous colour-fields.

“He was making a comment about the end of film, I suppose,” says Loftus-Hills. “In the digital era, film is on its way out. But a lot of artists are going back to the origins of photography and analogue processes, challenging the digital age in that sense.”

In other works, the analogue and digital merge – such as in a 2007 series by Chantal Faust, Milk, in which the artist placed a cut-glass bowl of milk on a scanner bed. Loftus-Hills describes these as “digital photograms.”

Even in the recent days of film, processing was generally outsourced: negatives handed over to be processed by a professional, returning magically as printed images. Loftus-Hills hopes that, as well as showcasing a number of important works, Antipodean Emanations will shed light – so to speak – on the photographic process and its experimental possibilities.

“It really takes you back to the basics of photography,” she says of the exhibition, “and I think that’s important for anybody’s understanding of the medium and what the medium is about. Our expectations of a photograph are normally that they’re a window onto reality, but these works remind us in practical terms of what the photograph is.”

What it is: light, time, chemicals. In fact, it’s arguable that, far from being crucial to the process, the camera is in fact merely a convenience – a labour- saving box that contains and streamlines these elements, eliminating chance and the hand of the artist. In the digital age, artists working with cameraless photography continue to push the boundaries of experimentation, producing technically and conceptually challenging images of real beauty.