Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

In An unorthodox flow of images at the Centre for Contemporary Photography, the arrangement of the exhibition mirrored the title. Starting on the right side of the wall a salon hang of 150 photographs, images and videos snaked around the gallery across all four spaces. Yet this straightforward introduction belied an exhibition that was as sophisticated as it was accessible. Curated by Pippa Milne and Naomi Cass, their methodology melded taxonomy – the grouping together of like things (and the hallmark of curating) – with a looseness of selection that resembled the cascade of images found on Tumblr, Facebook and Instagram.

At times these pairings were overt while others were charged with ellipses. A photographed marble sculpture head by Andrew Hazewinkel was paired with a smaller photograph by Ian Dodd showing the same view of a woman, her stray wet hairs clinging to her neck, their likeness deepened by the black and white tone of both works. There were no wall labels to identify these pieces, rather, a catalogue described as a ‘field guide’ was provided. This method encouraged the viewer to focus on associations between each work, perhaps picking up on links intended by the curators, or filling the gaps with their own thoughts and narratives. It also created an egalitarian plane as journalistic snapshots were paired with photos firmly classified as ‘contemporary art’, and a somewhat flattening of time as historical work accompanied images from the present.

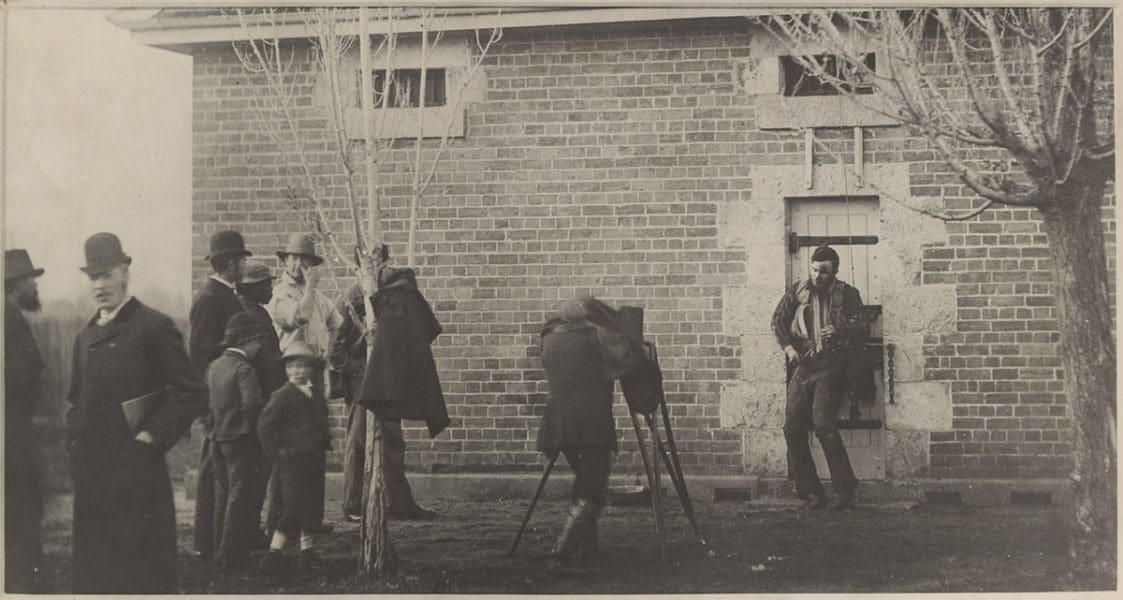

The exhibition began with what is thought to be the first press photograph in Australia: Body of Joe Byrne, member of the Kelly Gang, hung up for photography, by Benalla by J.W. Lindt (1880). This was a public spectacle of death, a theme and concern that has pervaded photojournalism. Beside this work hung two smaller images from different time periods: a digital print of Piero della Francesca’s Flagellation of Christ (1455-1460) and a shot by photojournalist Joosep Martinson Police Hostage Situation Developing at the Lindt Café in Sydney (2014). As well as their violent subjects, these works were connected by their compositions, suggesting how the arrangements of line and form within images can sit in the subconscious and influence how artists (and non-artists) view the world.

Works by Indigenous artists were placed throughout the exhibition as opposed to the problematic tendency to separate them from ‘the rest’. Leah King-Smith’s c-type print Untitled #3 (1991) from the series Patterns of Connection embodies the conflicted feelings that Indigenous people often have toward photography. On one hand photography was used as an instrument of colonisers as they ‘documented a dying race’, while on the other, these works provide a record of and connection to history. King-Smith reflects this ambivalence by overlaying colonial portraits of Indigenous people with her own photographs of the landscape, suggesting both a haunting and a returning of land to those dispossessed.

Certain works in the exhibition embody this explicitly, such as a photograph of Anne Frank’s bedroom wall documenting her movie star poster and postcard collection. A subtler work, and one that required contextual knowledge to fully appreciate it was Olive Cotton’s Moths On the Windowpane (1995). This black and white silver gelatin print, an abstract rendition of what the title suggests, was shot at the end of her life, while Cotton was infirm and domestically confined.

With this in mind, the work’s meditative nature suggests that the camera used by the artist is a tool for making sense of the world, a drive that shaped the medium’s history.

If we view the Internet in a positive light, it could be described as a rhizome through which we take a meandering path as we navigate from site to site. At times we stumble on something new – words, an image, an idea. This exhibition created a comparable experience in the physical world. The final video work in the exhibition is Francis Alÿs’ Fitzroy Square (2004), which was designated its own room. This video reflected this oscillation between engagement and the never-ending stream of images encountered in the outside world.

A man walks beside a fence running a wooden baton along it, creating a repetitive motion – this mirrored the process of viewing the exhibition and the endless ow of images that we encounter in every day life.

An unorthodox flow of images was held at the Centre of Contemporary Photography in Melbourne, from 30 September to 12 November 2017.