Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

The weight of every building in the colony sits heavily on the land, weighing down Country already deeply wounded by the digging of foundations, by the clearing of space, by the construction of structures.

Like many of us, Yamatji and Yued Noongar artist Amanda Bell took a long winding path before becoming an artist, living a storied life before trying to tell those stories, transitioning into an art career at an age considered too late by some. Although I would not consider her old, she says to me, when we speak over Zoom, “I’m at the start of old, that’s how I see myself at 59”. Coming to art relatively late is not common for mainstream artists but is surprisingly normal for Indigenous artists. Many of our greatest artists like Sally Gabori, Rover Thomas, Paddy Bedford and Emily Kame Kngwarreye waited until they were elders before making their first works of art; delivering in that way art containing wisdom greater than younger artists possess.

Bell worked for years as a social worker but found it too limiting, wanted to express her understandable and perfectly reasonable anger at colonisation. “I used to be a social worker and work in mental health, now I’ve come out of that there’s a freedom.” So now Bell is making art infused with the power of all the wisdom she gained from her working life. She doesn’t like making artists statements, preferring poetry, and is not the greatest fan of doing interviews. “The reason I’m a visual artist is I’ve spent many years toiling away at the public service going to meeting after fricking meeting speaking and speaking and talking and it’s very tiring, so that’s kinda why I am doing visual arts,” she tells me.

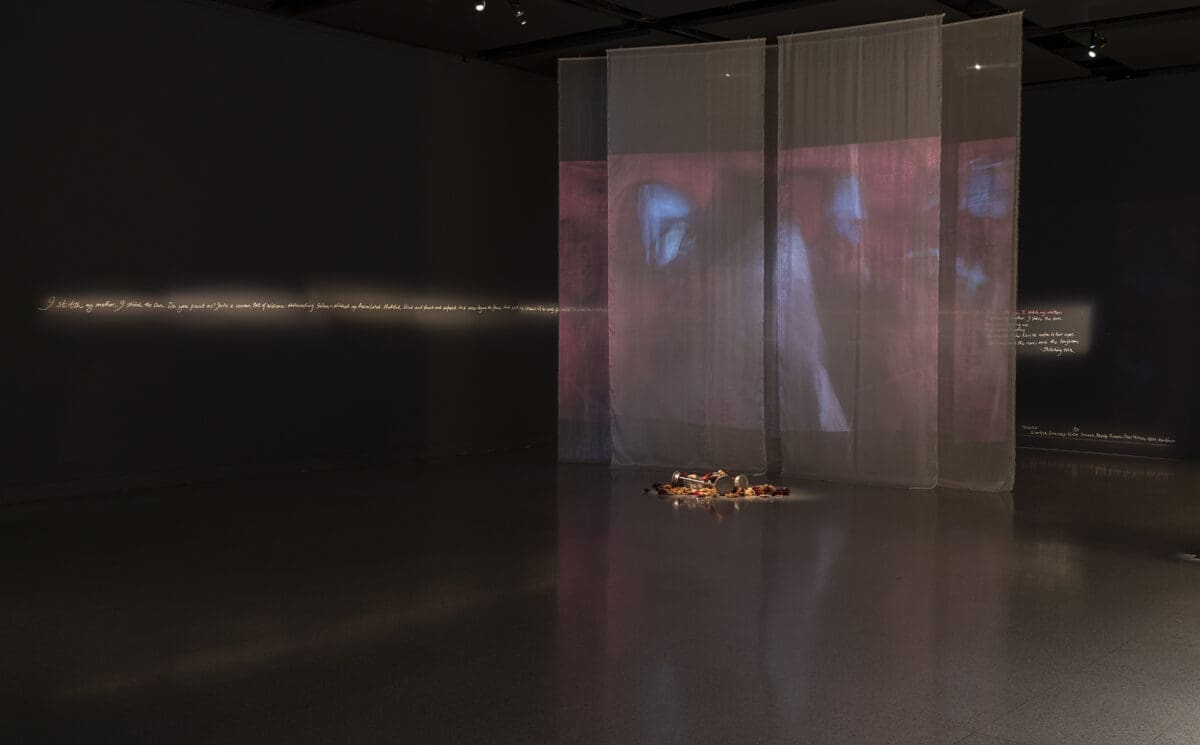

F = m * a: five ways to make a rainbow, her new installation for the Perth Institute of Contemporary Art is the third annual Judy Wheeler Commission, a series of works that respond to PICA’s history. It engages with the site as a form of loving protest, respecting the building while protesting its very existence. “I was interested in what happens when those bricks in the building collide with the Earth, collide on boodjar,” she says. Boodjar is the Noongar word for Country, and encompasses all that Country is to Noongar people, the land itself and the stories on that land. While the building is imposing and imposed upon Country, sitting upon it like a weight, crushing the land below it, Bell’s art is light. She explains, “I wanted everything to rest lightly on the building because I wanted it to be the antithesis of force”, both figuratively and literally, making no, or minimal and reversible, changes to the building. This is in stark contrast to the complete destruction of the sacred land on which it was built.

So, “the idea was to make rainbows in the building,” she says. Rainbows are structures made of light itself, paintings crafted by sunlight, by physics, by photons, beautiful but insubstantial. Made of light they sit lightly, having a powerful presence despite their in substantiality.

Working with the entire building gives the artist scope for a larger intervention. “There’s an audio component as you ascend the stairs that will come up from the floorboards that I’m hoping is just uncomfortable,” she says. The sound is to articulate, in some sense, the pain and fracturing of boodjar suffering under the weight of the building and the “building and all it represents meeting boodjar”.

The work is both site-specific and, in a way, durational, existing in and engaging with the site for an entire year. “I have a whole year to add to it, as the seasons and the sun changes what might not work well in summer; when you get more sun through that building, because of where it’s placed, it might work in winter,” she says. “There’s always hope that it can be added to or changed in some way through the seasons.”

It’s important to engage with institutions at the very level of buildings themselves, to remember that historic buildings were built on this continent without the approval of the real owners of the land. Now they are respected more than ancient sacred sites. There’s an uproar when heritage buildings are destroyed or modified, not when a sacred site is completely obliterated by mining. There are laws protecting old buildings while the world’s oldest art, at Burrup Peninsula in the Pilbara, is at risk. As Bell says, “I haven’t been doing this stuff that long, but I have always wanted to speak about these things, and I’ve never just been able to find a way.”

That is part of the power of art, to speak loudly when nobody wants to listen; to tell the unpalatable stories in powerful and beautiful ways.

In the end there is one important thing that Amanda Bell and I have in common; something she says to me, something I understand right into my bones, “I’m only in the arts, fundamentally, to be part of change.” That is why I personally became a writer and artist, to be part of changing culture for the better. Being able to do that is a part of art to the bones.

F = m * a: five ways to make a rainbow

Amanda Bell

Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (Perth/Boorloo)

On now—21 December

This article was originally published in the March/April 2025 print edition of Art Guide Australia.