Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

In late 2021 Melbourne artist Damiano Bertoli died unexpectedly. He was 52. An artist and writer who worked across drawing, theatre, video, prints, installation and sculpture, Bertoli was deeply embedded in the Melbourne arts community.

With works of great humour and intelligence, Bertoli was best known for his ongoing series Continuous Moment, which sprawled a range of mediums across multiple works, ultimately circulating on time itself. His practice gravitated toward aesthetic and cultural moments, particularly related to his birth year of 1969.

Ahead of Bertoli’s retrospective at Neon Parc, we asked those who knew the artist to each write on one of his works. Read the words of artists Darcey Bella Arnold and Yanni Florence, writer Amelia Winata, and Neon Parc director Geoff Newton.

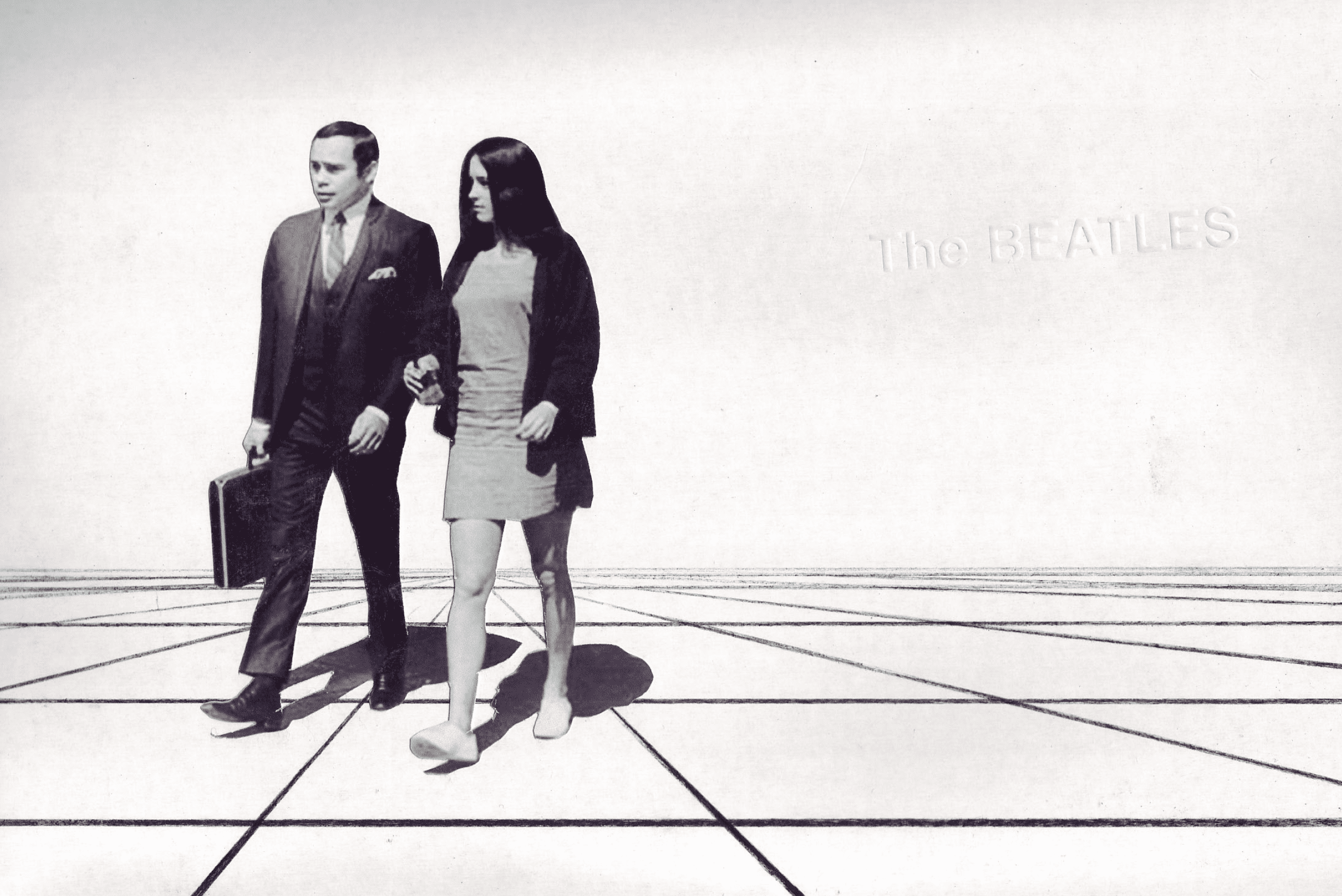

Amelia Winata: Born in 1969, Damiano used his birth year as a starting point for much of his work. The year spawned plenty of cultural touchstones, including the Tate-LaBianca murders by the Manson Family on 9 August 1969.

Here, Bertoli has superimposed an image of Vincent Bugliosi—the attorney responsible for the Manson Family murder convictions—next to Susan Atkins, one of the convicted murderers. The two have been collaged over a grid made famous by the Italian architecture firm Superstudio, best known for its antiarchitectural concept Continuous Monument. Damiano riffed off this title for his own career-long project, Continuous Moment. The interconnected visual language of the grid befits the past/present/future logic that underpinned Damiano’s practice. Meanwhile the Beatles ‘White Album’ cover is the work’s base, a reference to Charles Manson’s supposed belief that the song ‘Helter Skelter’—which appears on the album—contained subliminal messages said to have prompted the murders.

In 2015, Damiano exhibited a collection of his Manson Family works at TCB artist-run gallery, titled Come to Now. He painted each of the gallery’s walls in an opulent red or blue, creating cohesion throughout. It resembled a large-scale installation, epitomising Damiano’s pursuit of a complete artwork.

This was my (shockingly late) introduction to Damiano’s work and I was blown away by how perfectly executed it was. Since then, I have used Come to Now as a benchmark for what a good exhibition might look like.

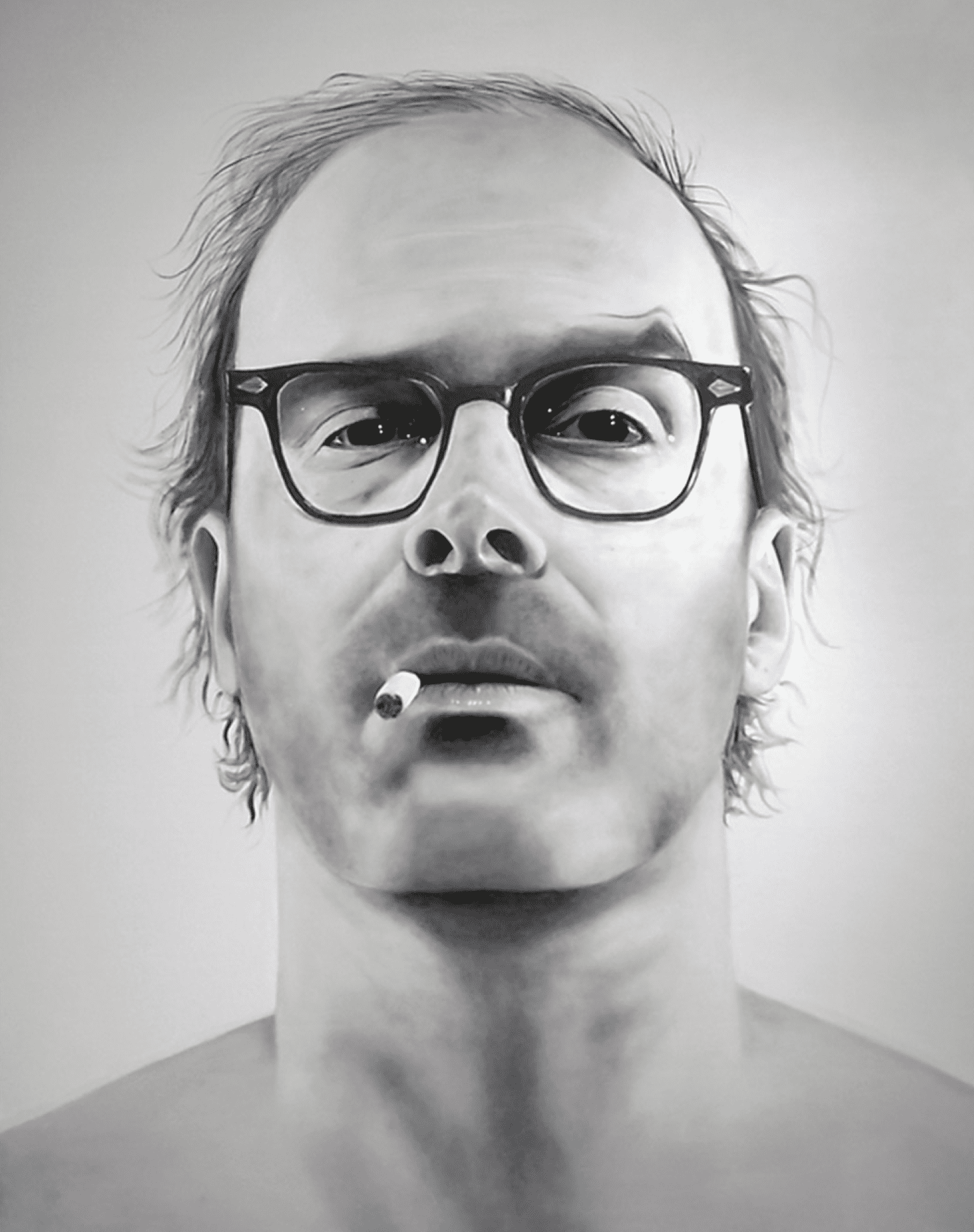

Darcey Bella Arnold: I first met Damiano around 2004 as a drawing student at the Victorian College of the Arts. Seeing his work in the group exhibition New07 at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art—a presentation of collage, sculpture and painting—had a great impact on me. Sophisticated in high and low media, humour and intensity, the installation can be summed up in Damiano’s hyperrealist self-portrait as the American artist Chuck Close, Does my brain look big in this?

The original Chuck Close portrait was presented in Damiano’s birth year of 1969. For New07 Damiano added a comic title—a layer of satire that speaks to the posturing of art. I am struck by its technical delivery, and by the subject’s intense gaze; Damiano stares down at the audience in Chuck Close glasses and a cigarette. Very cool. Very Damiano.

I see this portrait in some ways reflecting how Damiano approached teaching. He was very comfortable to talk to—not excessively academic. He would ask what parties or gigs you’d gone to, then get to questions around art making and culture, and then he would bring these conversations back to the work you were creating. Before he passed, Damiano spoke to me of how much he was enjoying teaching TAFE. He explained the students weren’t “uptight reading Derrida”— that he was enjoying their unaffected nature, unconcerned with their perceived level of knowledge.

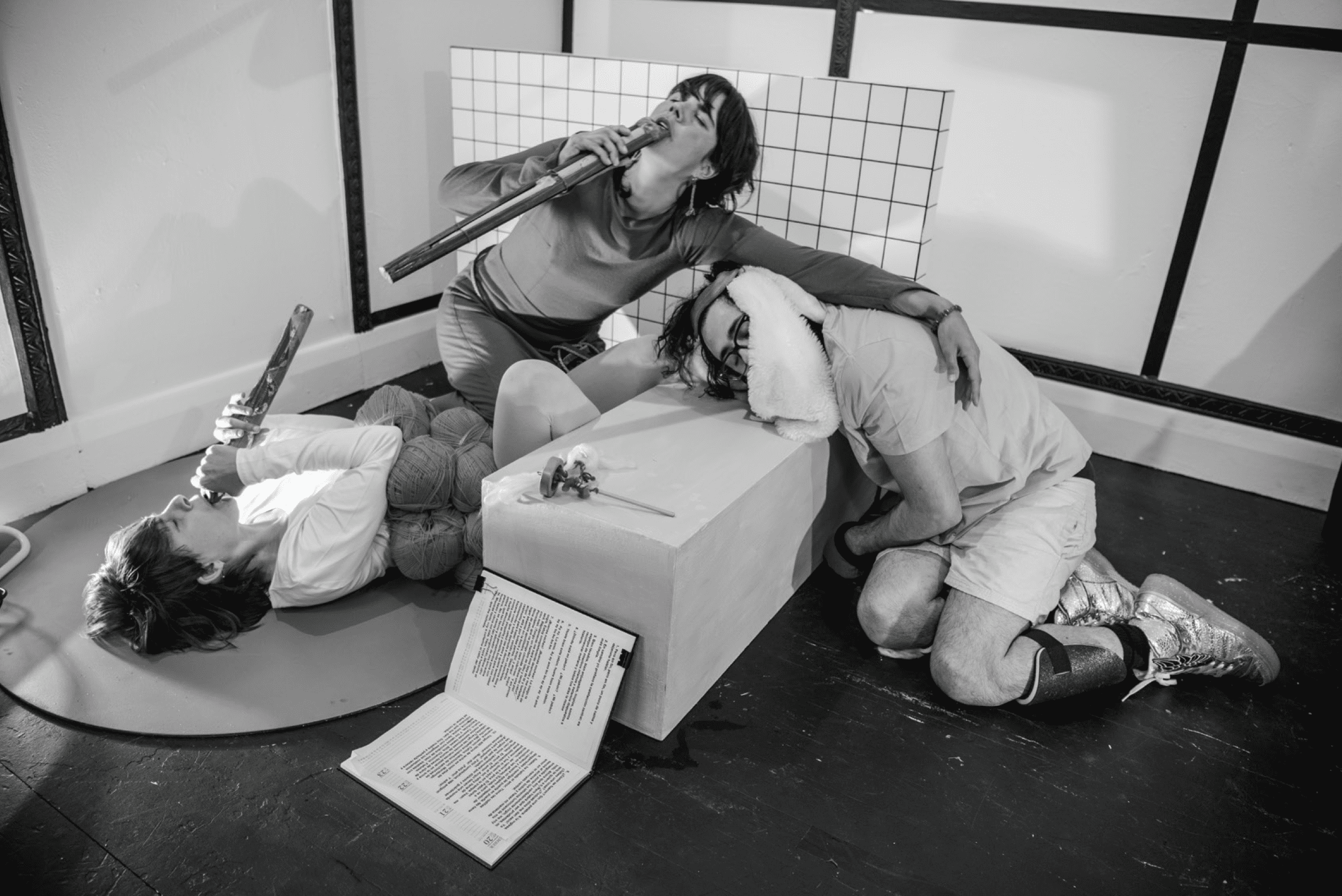

Yanni Florence: On Sunday 24 June 2018, Damiano rehearsed Le Désir / Dejeuner—his version of Pablo Picasso’s 1941 play Le Désir attrapé par la queue. It was for a performance on the next night for the Melbourne Art Theatre curated by John Nixon. Damiano had staged the play once before, planning for three times in total. He emphasised the ‘three only’ performances.

The rehearsals and performances had the romance of theatre that you hope for. Damiano and John sitting on stage quietly talking. The performers made up of Damiano’s students and artist friends, all chatting and joking in the eclectic costumes Damiano designed. The roles, costumes and set design were full of the art history references that permeated his work. Damiano was himself in a wig, looking like David Hockney, and a necklace of round balls—a ridiculously large caricature of one worn by Simone de Beauvoir. You could decipher some references—and what you couldn’t was amusing or unsettlingly absurd.

It was a full house, set in an old theatrette in Melbourne that’s original purpose was for models to parade lingerie to department store buyers. At the end, Damiano and his performers stood at the edge of the stage and bowed. The audience clapped, having been transported to the halcyon days of avant-garde theatre. We became part of Damiano’s ongoing artwork series, Continuous Moment.

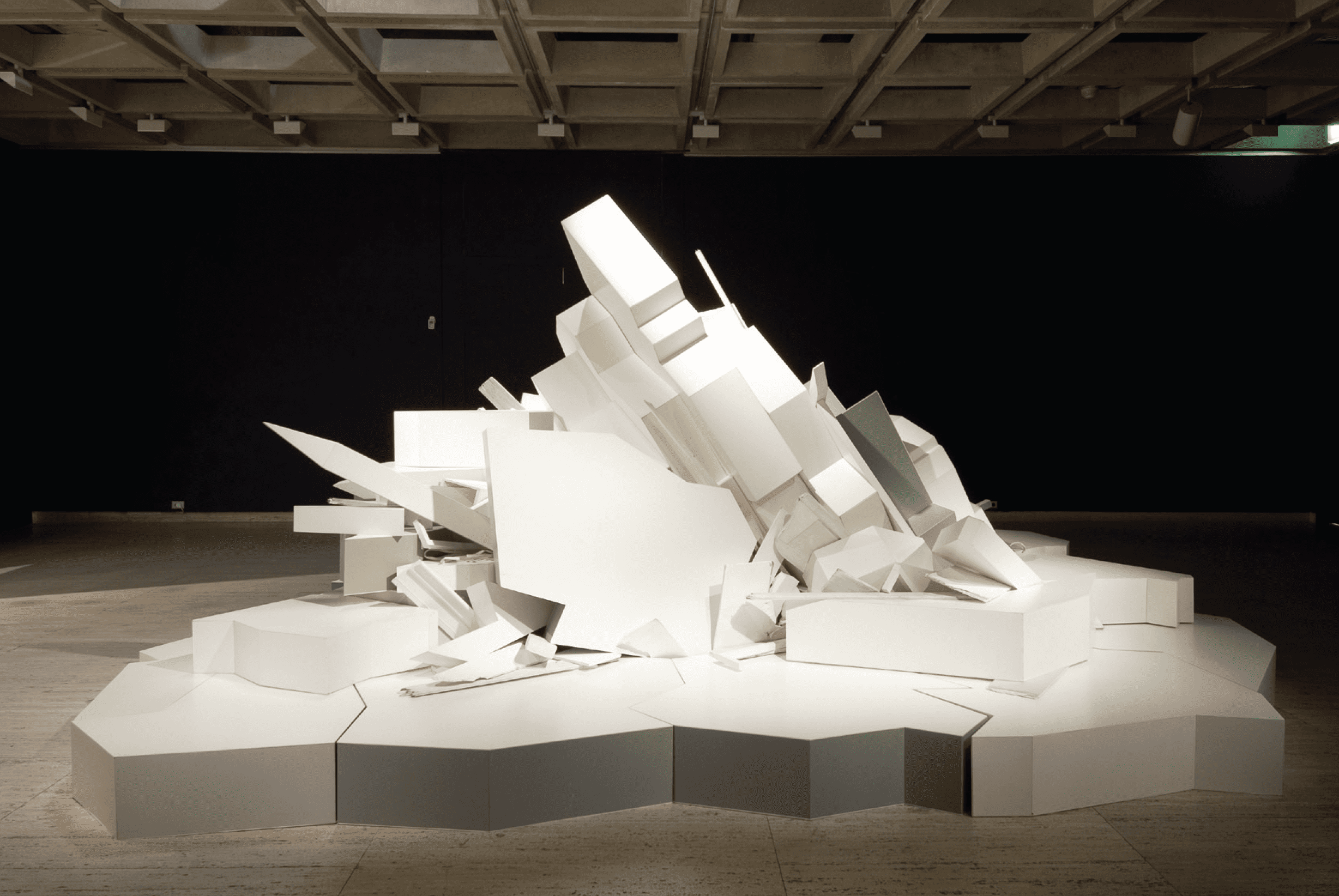

Geoff Newton: Continuous Moment, the title of the above work and Damiano’s series, is at once clever, arresting and monumental. For me, this artwork is when Damiano becomes Damiano. With an ambitious scale, it’s made of jagged, white, plastic edges and protruding fluorescent tubes, which are piled on top of a sprawling, knee-deep jigsaw of white-grey icebergs. It was something to behold: a giant, stoic, cool island. Frozen, and great from every angle. Like a lot of good work, it didn’t need any explanation. You felt it came into existence and just had to be there. The perfect monument.

In the painting that Continuous Moment references—Das Eismeer (The Sea of Ice), 1823-4, by German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich— the artist imagines what an iceberg looks like, capturing a colossal shipwreck in the Arctic, a place he’d never seen in person. The work was unsold when Friedrich died in 1840, yet is considered one of his masterpieces. Following the exhibition of Continuous Moment at Gertrude Contemporary, then at National Gallery of Victoria, National Gallery of Australia and Art Gallery of New South Wales, Damiano used the same title to reference his concept of the artists’ studio as a place where multiple histories could exist at once— or come together in the act of creation. Time travel, via the hand of the artist.

Damiano Bertoli

Neon Parc (Melbourne VIC)

14 September—1 October

This article was originally published in the September/October 2022 print edition of Art Guide Australia.