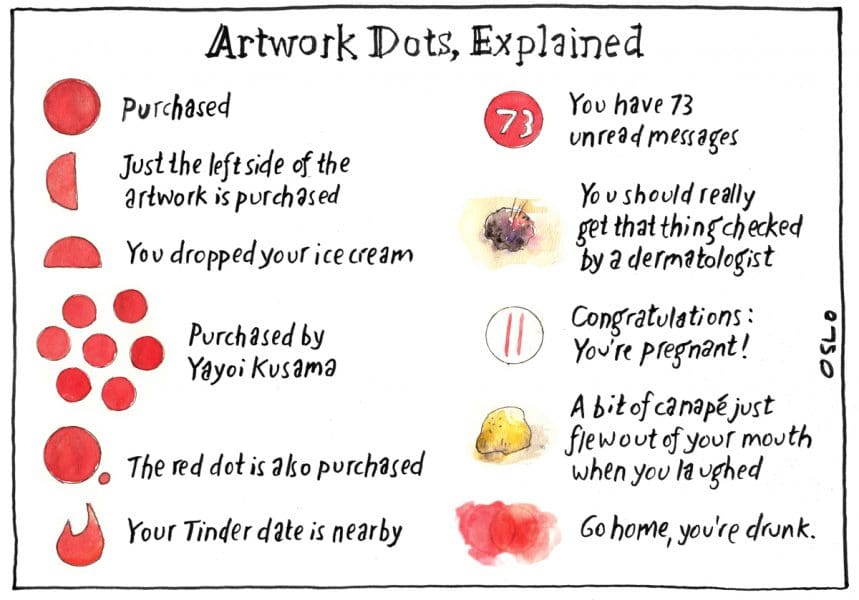

Walking around the recently held art fair, Sydney Contemporary 2017, I noticed, here and there, a sticker that’d been placed near select works: ACQUIRED BY ARTBANK – AVAILABLE FOR LEASE SOON. This was a very canny move – not only was the organisation letting you know what they’d purchased for their collection, they were telling you that, even though they’d got in first, they’d be willing to share it with you. While all the galleries at the art fair were pitching their art at prices that’d match the buying power of the market’s range of art collectors – from newbies to established collectors to patrons – Artbank was advertising what it had actually purchased. Imagine if the red dots at exhibitions and art fairs actually came with the name of the corresponding buyer – it’d change the market forever.

It’s an oft-repeated truism that the art market is the largest unregulated money market in the world.

That’s the headline stuff that people like to repeat to each other at openings and art fairs, but at ground-level, as a writer, I have yet to meet a gallerist who is completely open about their business, from artists and sales, to the market or government regulation. The combination of self-interest and enlightened PR makes even the most casual conversation an opportunity to put forth an agenda.

Admittedly, some gallerists are more forthcoming than others, but the actual mechanics of their business are always kept discreetly from view: it’s proprietary information and they’re not going to reveal anything substantial to a blabbermouth art writer. To try to take the temperature of the market, one had to rely on a huge pinch of salt, and keeping one’s eyes open.

On the basis of walking around and just looking at what was on offer, one came to the rather unsurprising conclusion that, as far as the business of buying and selling is concerned, and if this year’s Sydney Contemporary can be taken as a reliable measure, the market is in the grip of deep-freeze conservatism. There was a range of work to meet most tastes – from the value-for-money realist painters that give collectors the benefit of their prodigious craft skills, to the deliberately de-skilled faux naïve picture makers and smash-it-against the wall ceramic artists, to a few rare examples of what used to be called ‘video art’ that also act as soothing décor, to some attractive photography.

It was all there, and looking at the art fair was like flipping through the pages of a glossy catalogue.

In comparison to recent years, at both Sydney and Melbourne’s art fairs, here there were very few if any ‘show stoppers’ like those gargantuan Quiltys or multi-panel Bartons once on offer. Even the size of the art was smaller, becoming domestic-scaled, and collectable. Where international art fairs will include secondary market dealers selling old masters and modernist icons, Australia’s off market offerings were pricey, but tame.

I recall being mocked for discussing the size of art works on offer at an art fair, but size matters. Imagine if a boat show only sold tinnies: you’d wonder where all the luxury pleasure craft had gone.

The forces that shape the market produce an art object of average taste, not too adventurous, not too tame, you know, just right. While there is some variation in the offerings, these can be accounted for from the taste of collectors, from the educated, careful shopper, to the impulsive ‘I don’t care how much it costs – I like it’ crowd. If there’s a more radical art market someplace, it’s one hidden from view, and one can only imagine the kinds of work it might sell. Perhaps the rarefied upper end of the market where collectors morph into patrons who are, not just buying work, but also donating works to public galleries for the tax breaks and the kudos, or even beyond that, becoming cultural institutions that commission work and open their own museums, maybe this would be the place where the contemporary art doesn’t look like all the other contemporary art, an event horizon where it ceases to be a commodity but an idea one can commune with.

It’s probably a category error to think the art market could be any other way.

Like a giant sieve, all art moves down the art market funnel to come out the other end as saleable objects. But the hunger for something else is real. Robert Hughes once called Australia’s art collectors of the late 1960s the ‘tyre kickers’ of cultural consumption – how much mileage am I going to get for my money? We like to imagine that the art market is more enlightened now, but if the real market is anything to go by, and the wares on offer at art fairs are any indication where the market is now, we’re no longer at a car yard, it’s all starting to look a lot like IKEA.