Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

In 1930 American artist Alexander Calder visited Piet Mondrian’s Parisian studio. While Calder was already well-known in avant-garde quarters for his circus-related works, the meeting with Mondrian led to his first understanding of abstraction. Although Calder would never be a modernist or abstract artist in a typical sense, the moment had a profound influence on the creation of Calder’s most famous works: his mobile sculptures. Considered to be a defining point in Calder’s art, this is one of many innovations chronicled in Alexander Calder: Radical Inventor.

In capturing both the artist’s career and singular spirit, the show elucidates Calder’s idiosyncratic approach to creating: his playful, inventive spirit; his entwining of modernism and popular art; his penchant for spectacle; his abiding interest in toys; and, perhaps his lasting legacy, the joining of contemporary art with kinetic movement. In capturing Calder’s prolific nature — he created over 22,000 works across six decades — the exhibition spans sculpture, painting, performance documentation, jewellery and illustration.

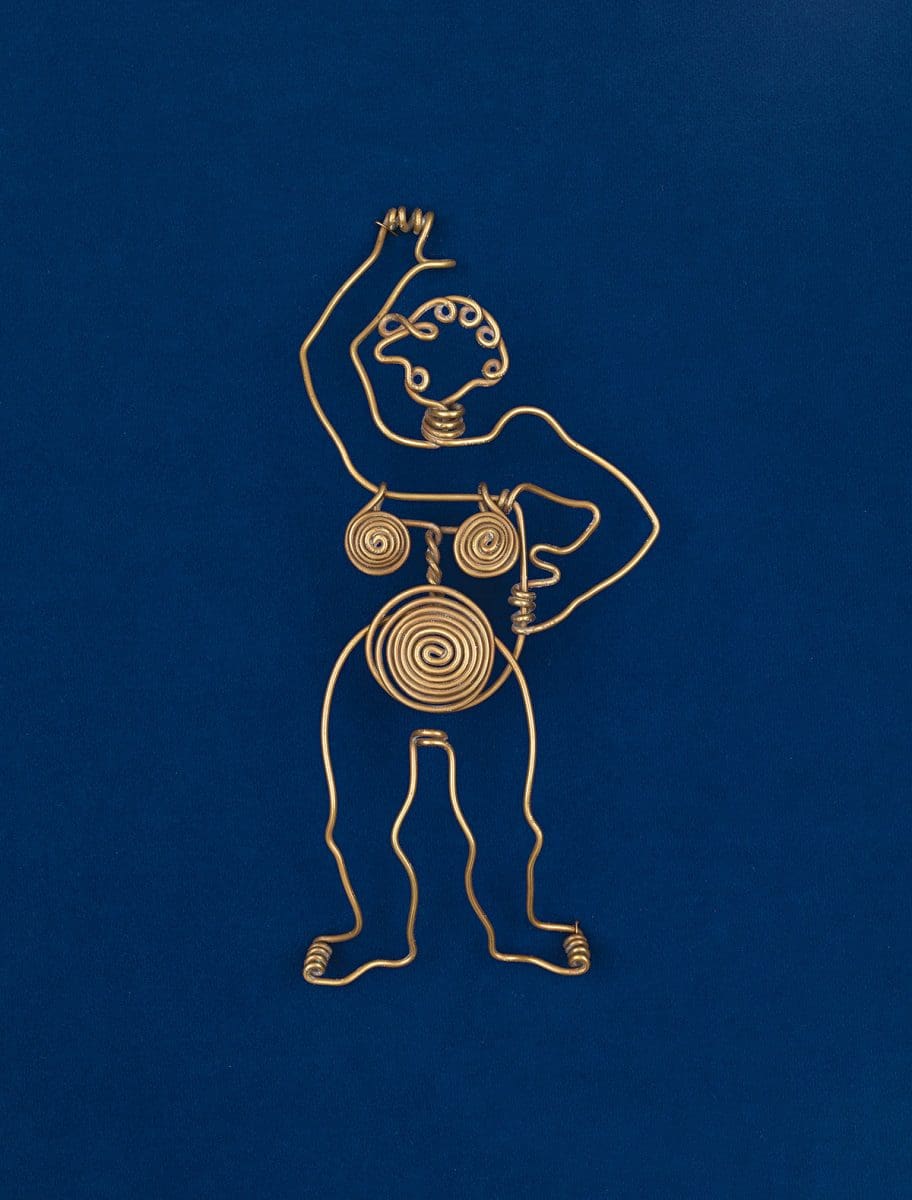

Looking back, it seems inescapable that Calder would be an artist. His parents and grandfather were respected artists, and from the age of eight Calder was already creating small animal sculptures from his own studio (pieces which are on display in the show). This early sense of play continuously resurfaces, particularly evident in his paintings and wire sculptures of circus performers, capturing twirlers and ringmasters in active yet harmonious positions.

Moving from America to Paris in 1926, Calder soon used the spectacle of the circus for his renowned Cirque Calder in which he created and performed his own miniature circus to a rapt Parisian avant-garde. Captured in the exhibition documentation, it marks the moment where viewers stopped looking at Calder’s work, and began watching: it brought movement, three-dimensionality and duration to art.

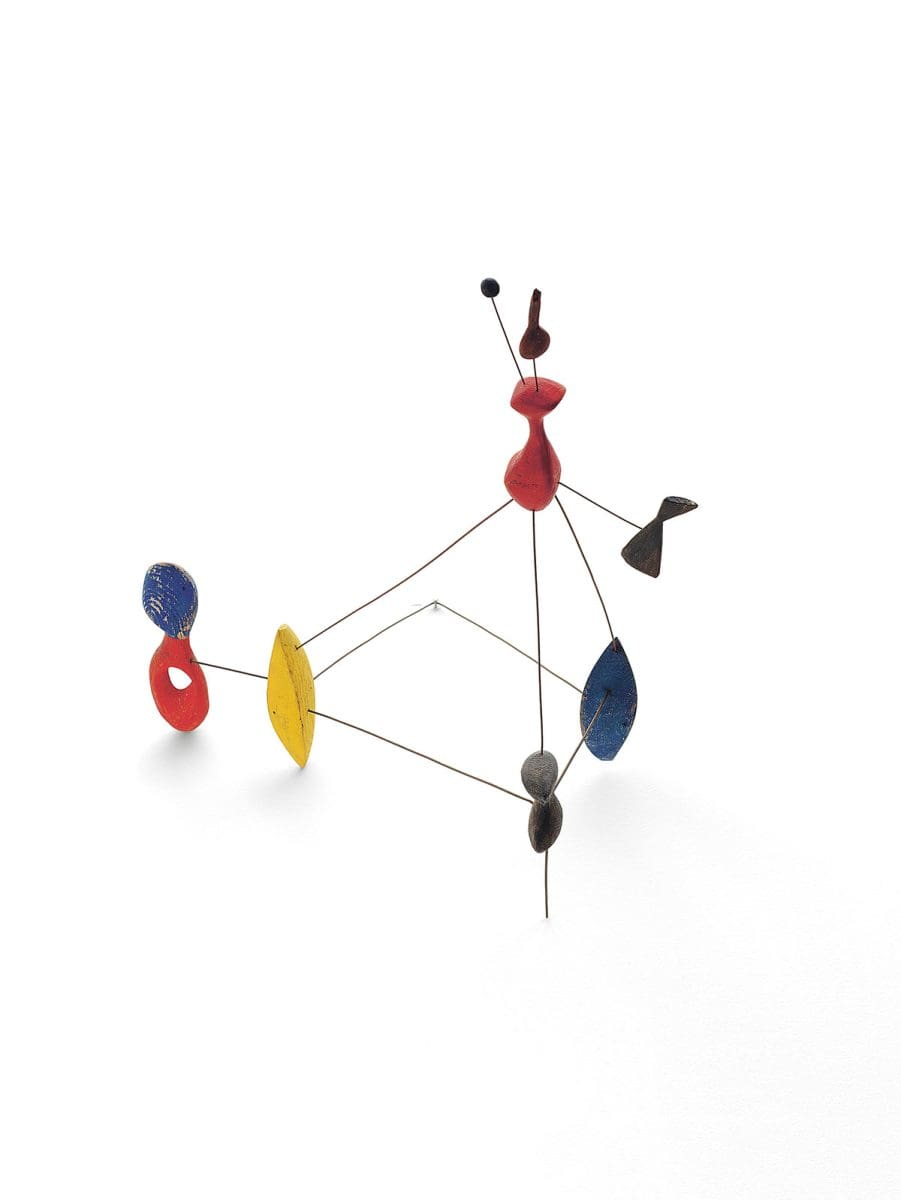

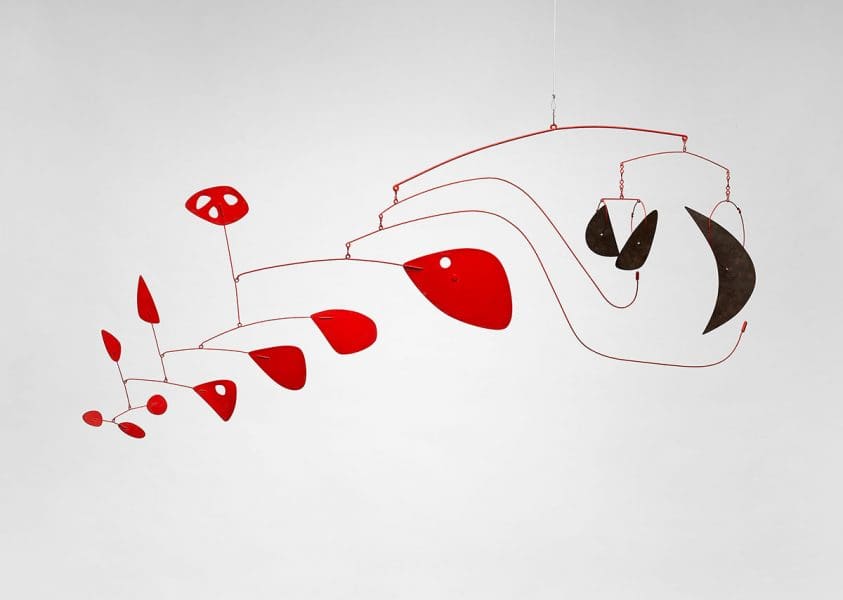

From here the exhibition chronicles Calder’s blending of playfulness, kinetic movement, abstraction and sculpture, culminating in the famous mobiles: large, hanging structures crafted from wire and sheet metal, moving in slow harmony. Duchamp would coin the term “mobile” to describe these pieces, and when Calder later created non-moving sculptures, Jean Arp dubbed these as “stabiles”. While Calder may not necessarily have worn the label of inventor over artist, Wallace explains that “it’s interesting to understand how creating a new artistic form, as Calder did, can be an invention.”

By the end of his life Calder stopped giving interviews as he felt people didn’t understand the complexity of his work. “He could be reduced to this humorous American and was never taken quite as seriously as his European counter-parts,” adds Wallace.

While Calder doesn’t fit neatly into the dominant narratives of either modernism or postmodernism (perhaps not abstract enough for the former, not politically engaged enough for the later), there is also the question of whether his playful persona failed to translate to early audiences. As Wallace explains, “The problem in interpreting Calder is that there is an element of play, and play has not been understood well until our contemporary period.”

Although we need not feel too worried for Calder (he did spend the last decades of his life engaged in numerous high profile public commissions), Wallace does point out that untangling his legacy has required distance. “It has taken time to understand him as this incredibly relevant and interesting artist who was making work that feels very contemporary,” she says. “And it feels contemporary because it is very participatory, very playful, and very much about the experience.”

Alexander Calder: Radical Inventor

National Gallery of Victoria – NGV International

5 April – 4 August