Material curiosities: Primavera 2025

In its 34th year, Primavera—the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s annual survey of Australian artists 35 and under—might be about to age out of itself, but with age it seems, comes wisdom and perspective.

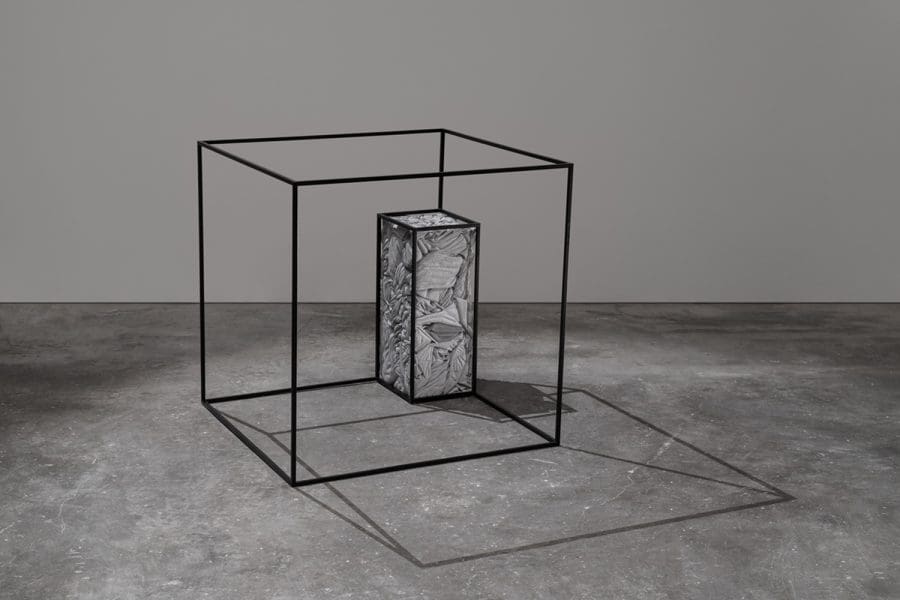

What does your life weigh? This is the unspoken question that resides at the heart of Alex Seton’s exhibition Cargo at Sullivan + Strumpf, Sydney. By way of answer the artist offers up seven marble sculptures that depict seven years of his old clothing. In the exhibition these trappings of the everyday are afforded a sculptural significance; they come to more closely resemble a Bernini bust than a pile of dirty laundry. But while Seton’s new works adopt a classical artistic vocabulary, they nonetheless retain a deeply personal resonance.

“The works are totems to the former self, to former lives and to former roles I’ve played.” In this sense, every curve and contour in each sculpture represents a corresponding change in the life of the artist. Ironically, the clothing exposes Seton’s own history, leaving him naked before the gallery-goer.

But Seton’s works transcend the personal and grapple with some of humanity’s most essential questions. “To carve your old clothing, which you would normally throw out in this day and age, has a political consequence,” he says. “So much fast fashion happens now, so much of how we treat materials now is as disposable.” Indeed, inscribed indelibly into the rock is the transience of our consumption. “It’s about slowing it down and making totems out of fabrics that are normally thrown out,” Seton explains. “The condensed clothing bales are like little crushed bricks of humanity.” Seton’s works take the most innocuous aspects of our quotidian existence and transform them into incisive rebukes of our most common and thoughtless practices. “This work really steps into the poetics of what bonds us, it talks about what we leave behind, about what is our legacy,” he adds.

However, the present concerns Seton as much as the future. His multivalent works deal directly with the artist’s ongoing preoccupation with Australia’s treatment of refugees – which again is a personal matter. “Australia’s refugee and asylum seeker policy no longer extends the good faith that, say, my mother’s family enjoyed when coming from Egypt in the 1960s,” Seton explains. “What is it to be a refugee but a person seeking a better life? And that is common to us all; it’s a deeply human trait that is written into the stories we tell each other.”

Yet Seton also surrenders to the reality that these concerns may not be readily apparent at first glance. “Whether you feel that when you stand in front of the work is a different thing,” he says. “I would never dare to tell people what to think.”

Cargo

Alex Seton

Sullivan + Strumpf Sydney

28 September – 20 October