Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

After reading at Oxford or Cambridge, the sons of England’s 18th-century peerage had one great rite of passage ahead: the Grand Tour. In their teens and twenties, the upcoming gentry went abroad, sometimes for several years, to taste the cultural delights of Europe. In Italy, facilitated by chaperones and family money, they would cultivate good taste and worldliness by encountering the art and architecture of the Renaissance and classical antiquity. “This was literally the beginning of tourism, of travel for pleasure and edification rather than commerce, war or marriage,” explains artist Andrew Nicholls. Hyperkulturemia collects the artist’s forays into the romance and revelry of the tour.

Visiting Florence in 1817, the French writer Stendhal approached the tombs of Machiavelli, Galileo and Michelangelo in the acoustic, vaulted Basilica of Santa Croce. Moved by the significance and nearness of this monument, Stendhal experienced a kind of cultural panic attack; dizziness, weeping, intense emotion and collapse. A contagion of theatrical public swooning at famous landmarks (known as Stendhal Syndrome or hyperkulturemia) swept among the British. “It’s a wonderful idea,” says Nicholls, “that a work of art could induce this overwhelming corporeal effect.”

Though hyperkulturemia is nonsense medically, the condition became a fixture of the tour experience, helped along by other factors: “It was summer, the galleries were crowded,” explains Andrew Nicholls. “These English boys were likely hungover and of course they wanted to appear in possession of a refined sensibility.”

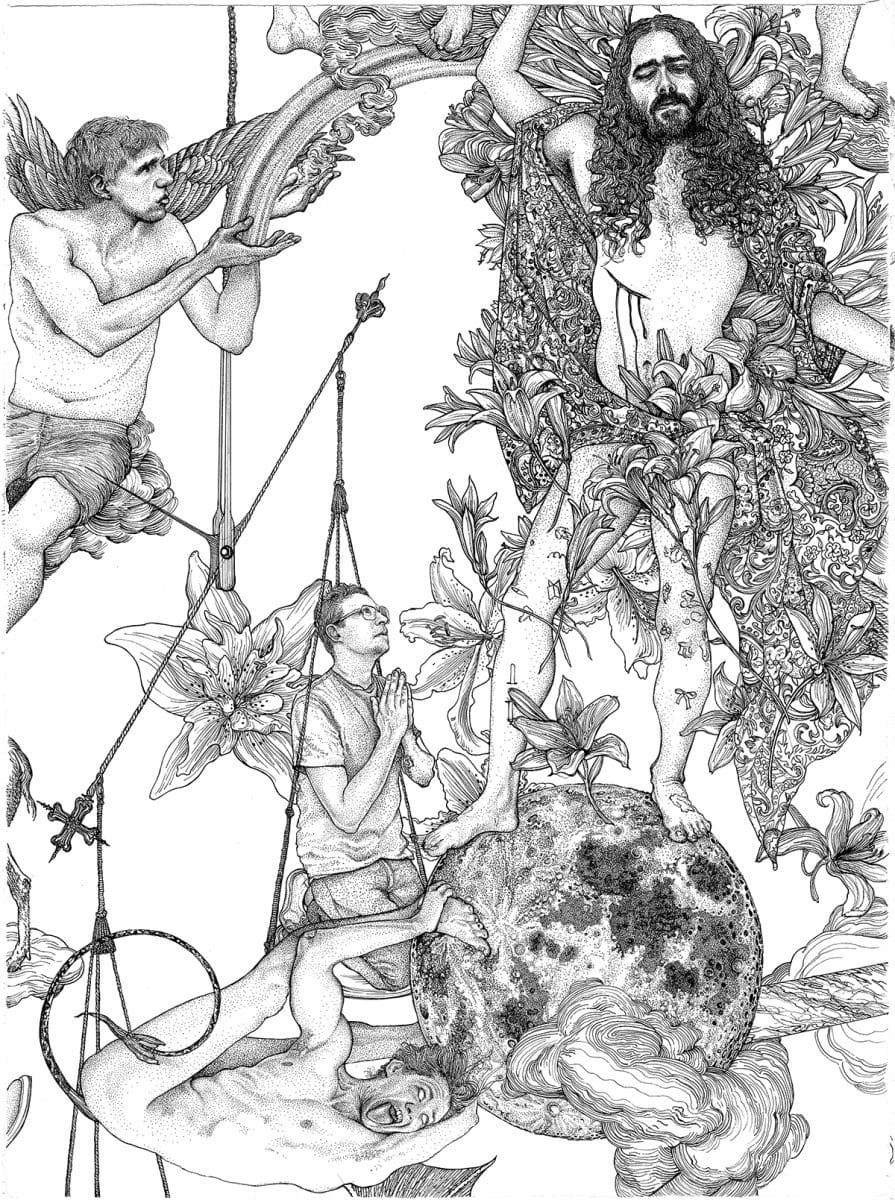

Has Nicholls ever experienced hyperkulturemia? “On my last day in Florence I was exhausted − galleried out − but I took myself to the Bargello. I saw some Michelangelos and a fantastic Adonis. Then I went upstairs. Donatello’s David was across the room.” Reproductions had turned Nicholls off the bronze: “its androgyny, the fruitiness, the weird hat; ordinarily I’d be all for it, but it made me uncomfortable. Yet, the second I set eyes on David, it transfixed me. I spent two hours just circling it.” In Stendhal Syndrome #1, 2015–17, Nicholls is photographed mid-faint, walloped by the sheer immediacy of the effete, contrapposto David.

Itineraries listed in 19th-century diaries and letters helped Nicholls to plot a series of residencies across The Boot. These memoirs described the English ambivalence for Italian food and people, and their indulgence in parties and prostitutes.

The lasciviousness of the continent was not lost on their parents. “There was a culture of panic around the returning sons: bewigged bi-cultural creatures, called Macaronis, dropping Italian and demanding pasta. Many had contracted syphilis or gotten someone pregnant.”

Hyperkulturemia had a long germination which began, curiously, with a Spode meat platter: “I remember obsessively staring at it as a child, in the family dining room.” This early experience of being starstruck by an art object was brought on by an English-designed Arcadian landscape, printed in cobalt on white porcelain. “An artist composited it from bits of Italy on their Grand Tour. Those imperial complexities are really important for the show.”

Supported by a local government travel fellowship, Nicholls set off with a rota of young male models, artists and companions. He walked the ruins of Hadrian’s Villa, partied in Venice, wore britches and white makeup in the piazze and hiked up aching-to-erupt volcanoes.

“On my 40th birthday I climbed Campi Flegrei,” he recounts. “There was steam rising and yellow sulphuric rock in the crater. Boiling mud flew onto my arm, which felt like a blessing from Vulcan; and very much in the spirit of the tour.”

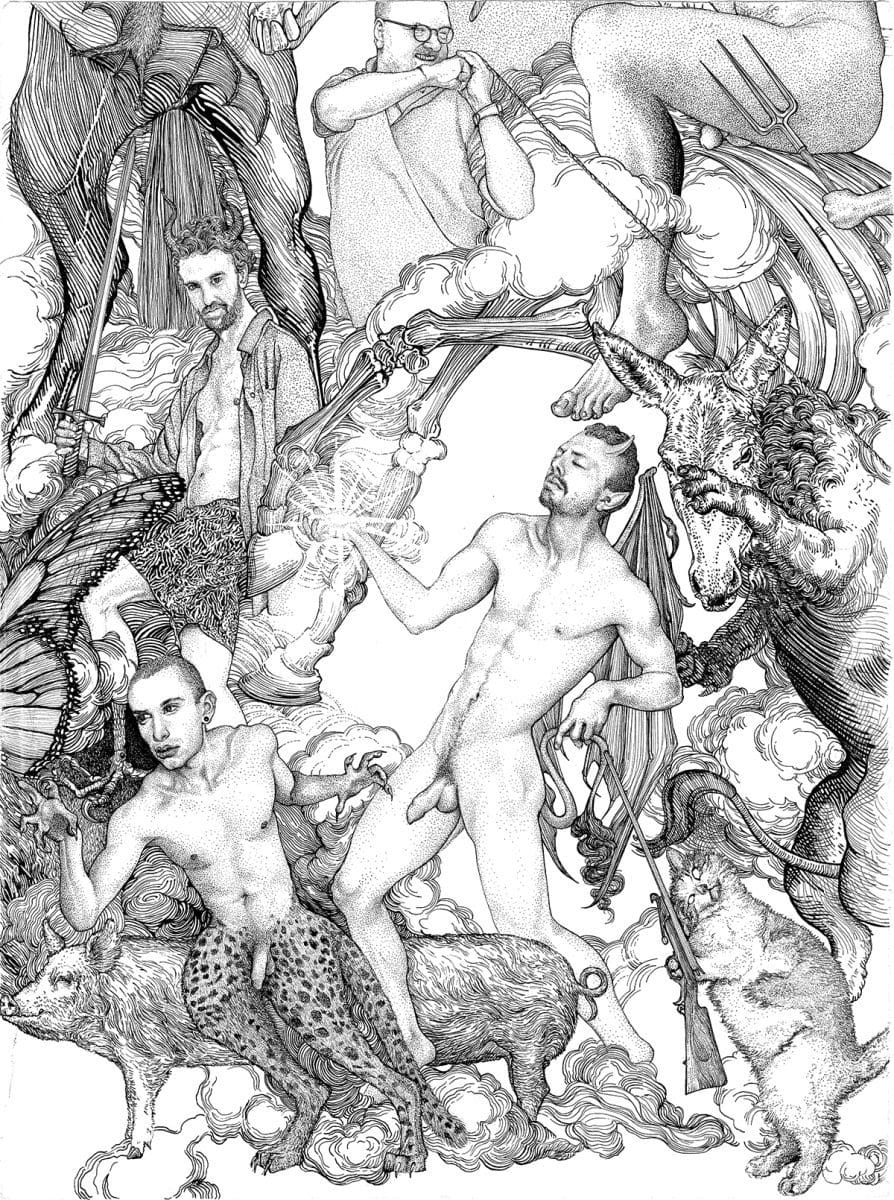

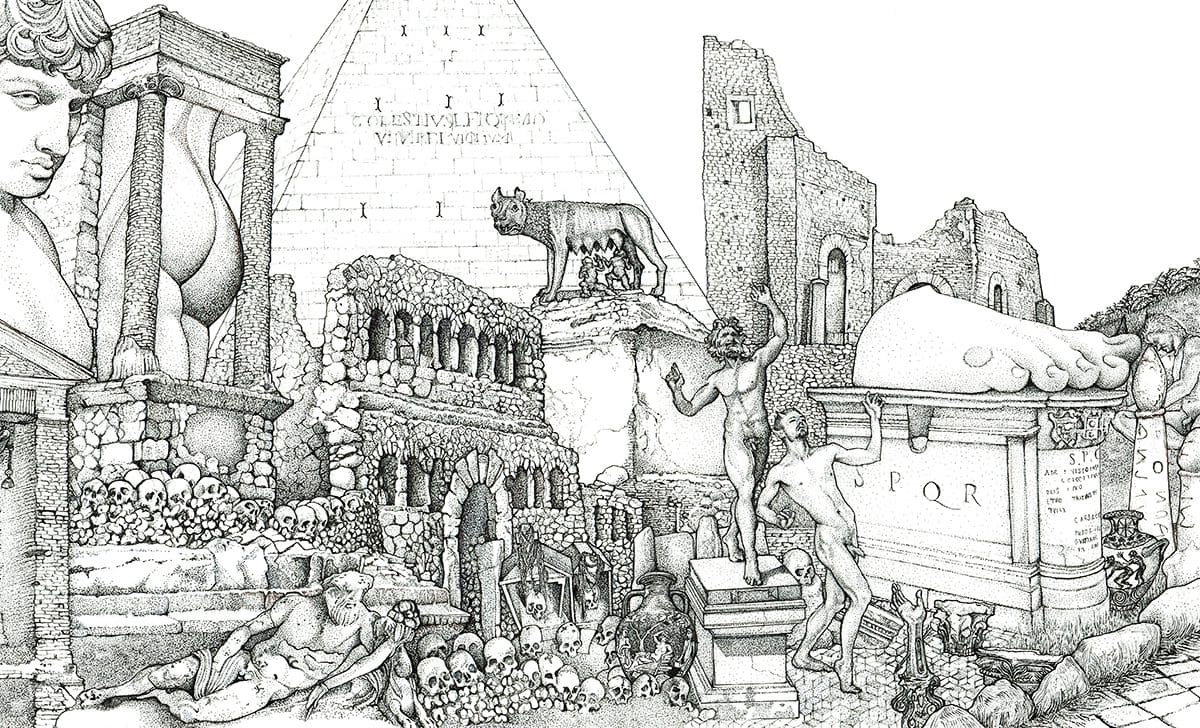

Nicholls carted a long scroll of paper onto which he made a slowly unfolding tour memoir: marble gods, cracked Corinthian columns, cobbled roads and his models, finely drawn in pen. Like the tourists, the completed frieze, Via Appia Antica (After Piranesi), 2016–18, imbibes the beauty and wisdom of the ancient world through its surviving monuments.

Festoons of cast porcelain bones hang throughout Hyperkulturemia; skulls and femurs ornamented with flowers in mimicry of Spode and Wedgwood. Made in Jingdezhen, China, the bones riff on the chinoiserie of the Nicholls family china, and Nicholls’ visits to Catholic ossuaries and reliquaries where rib shards and splinters of saintly scapula are enshrined in hammered gold.

In The Attitudes, 2015–18, Nicholls’ model, David Charles Collins, poses nude and splendid amid ruined aqueducts and stands of cypress. “With David’s physicality I could play with the symbolism of Italy as this place of transgressive sexuality and freedom,” says Nicholls. “He could pass as English aristocracy, yet he’s also somewhat godlike.”

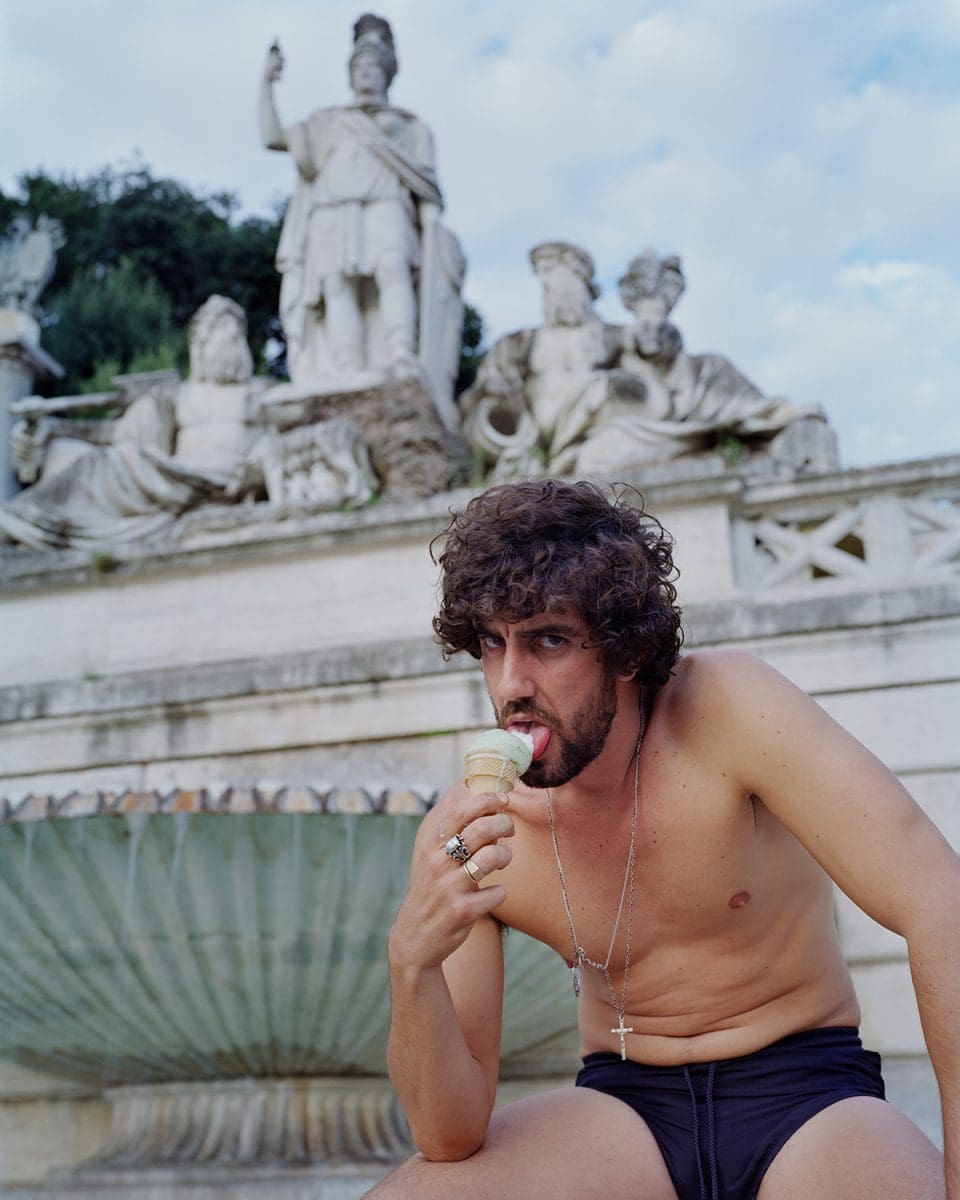

Sensual liberties of the past, like the after-dinner entertainments of the British Ambassador’s wife in Naples or the buttocks of the Venus de Medici, polished to a gloss by centuries of appreciative patting, reverberate through Nicholls’ photographs: the beau in Mangia Gelato, 2015-18, slowly licks fior di latte gelato, his gaze smouldering beneath curls.

With his English-Catholic heritage and besottedness with the promise of Italy, it’s tempting to see Nicholls as a Sebastian Flyte figure (of Brideshead Revisited). Yet despite his lyricism, the artist handles history deftly and persuasively. His work reminds us of the causal and familial relationships between antiquity and our lived, contemporary culture. Secreted in the ink drawing Via Appia Antica are some trees drawn directly from his Spode platter. Italy, empire, antiquity and Nicholls’ travels coalesce in this unassuming detail. “I’m using the platter for a celebratory dinner tonight,” he says, on the last day of 2018. “I’m making a beef wellington.”

WA Focus: Hyperkulturemia

Andrew Nicholls

Art Gallery of Western Australia (Perth Cultural Centre, Perth, WA)

15 December 2018—15 April 2019

This article was originally published in the March/April 2019 print edition of Art Guide Australia.