Poetics of Relation

Tender Comrade, currently on show at Sydney’s White Rabbit Gallery, creates a new vocabulary of queer kinship by reimagining the relationship between artworks, bodies and space.

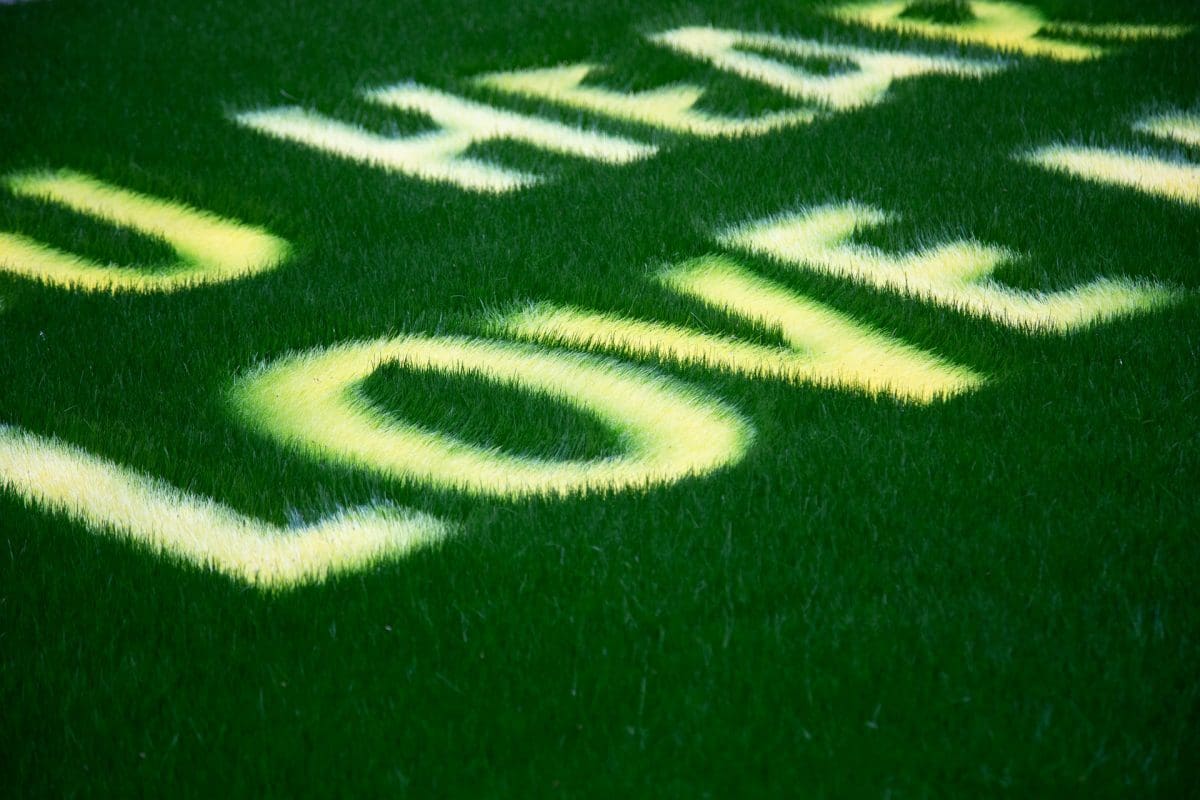

Last June, UK-based artist duo Ackroyd & Harvey launched a massive 16-metre-long slab of grass onto the River Thames. Emblazoned on the lush oblong of lawn were words written by acclaimed writer Ben Okri: “Can’t you hear the future weeping? Our love must save the world.”

Fused to a cork raft, the grass floated on the river, rising and falling with the tidal swell. Ackroyd & Harvey (Heather Ackroyd and Dan Harvey) love grass, which they have used as a primary art material for about 30 years to great acclaim. For them, it is a living substance that speaks powerfully to the ecological crisis we are living through. After all, photosynthesis is at the heart of supplying energy for life on earth, and for maintaining the oxygen content of the atmosphere. As they say, photosynthesis can be regarded as our “true economy”, the basic alchemy of all life, the “gold of the sun transmuting into the green of life”.

Grass is also central to the latest Ackroyd & Harvey project being installed in the entrance foyer of the Art Gallery of New South Wales as part of the 23rd Biennale of Sydney. The Biennale’s title rīvus—a word referring to rivers, wetlands and other salt and freshwater ecosystems—is perfect for Ackroyd & Harvey’s ecology-focused work, especially as grass is intimately connected with water.

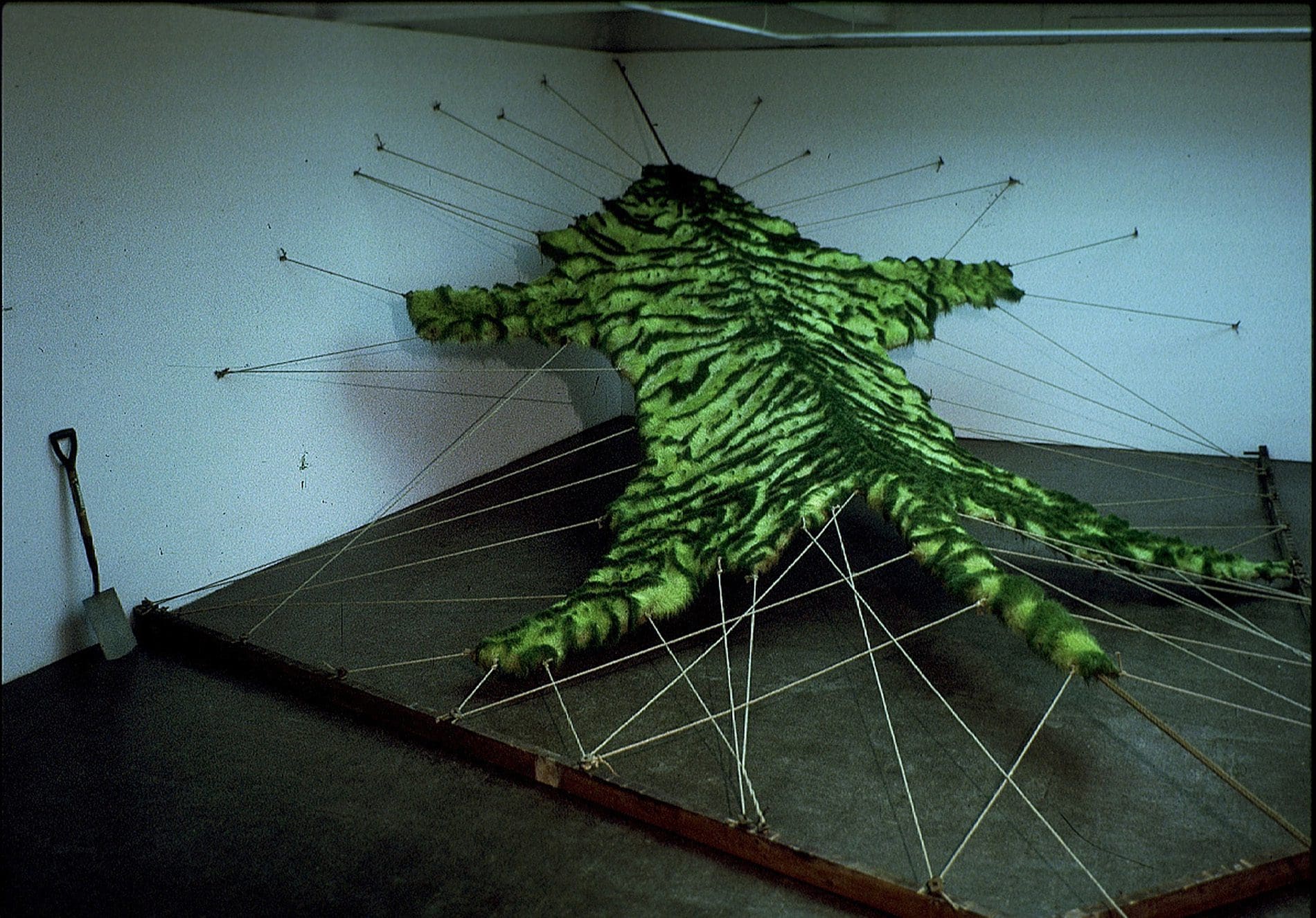

Operating beyond the usual parameters of art making, Ackroyd & Harvey entwine their practice with a spirited and vocal activism (they are also the co-founders of the group Culture Declares Emergency), and have created installations and sculptures of notoriety, recently showing at the Tate Modern. “Our work is always moving between art and activism, and more recently has focused on activism with the parlous state of multiple tipping points in terms of degradation of the environment,” Ackroyd says. “The science has been on the table since the 1800s. You can just see how it has become such a horrible political kicking ball.”

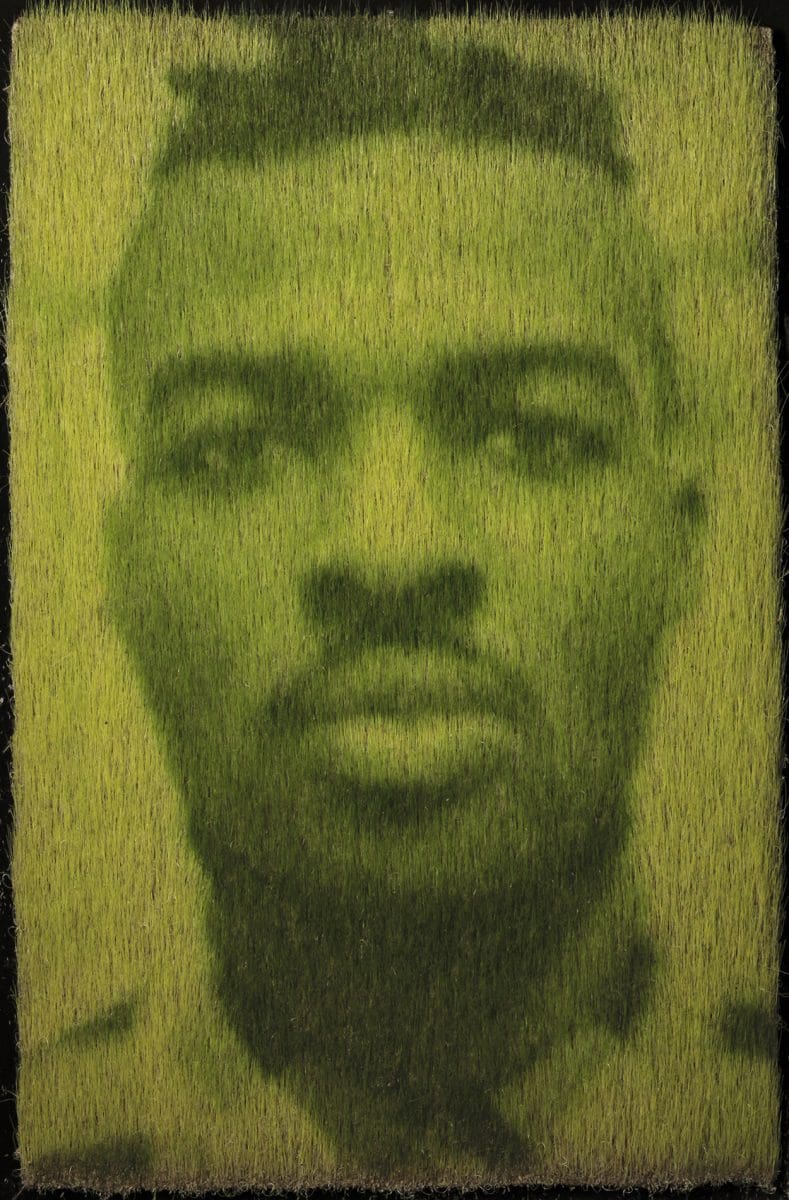

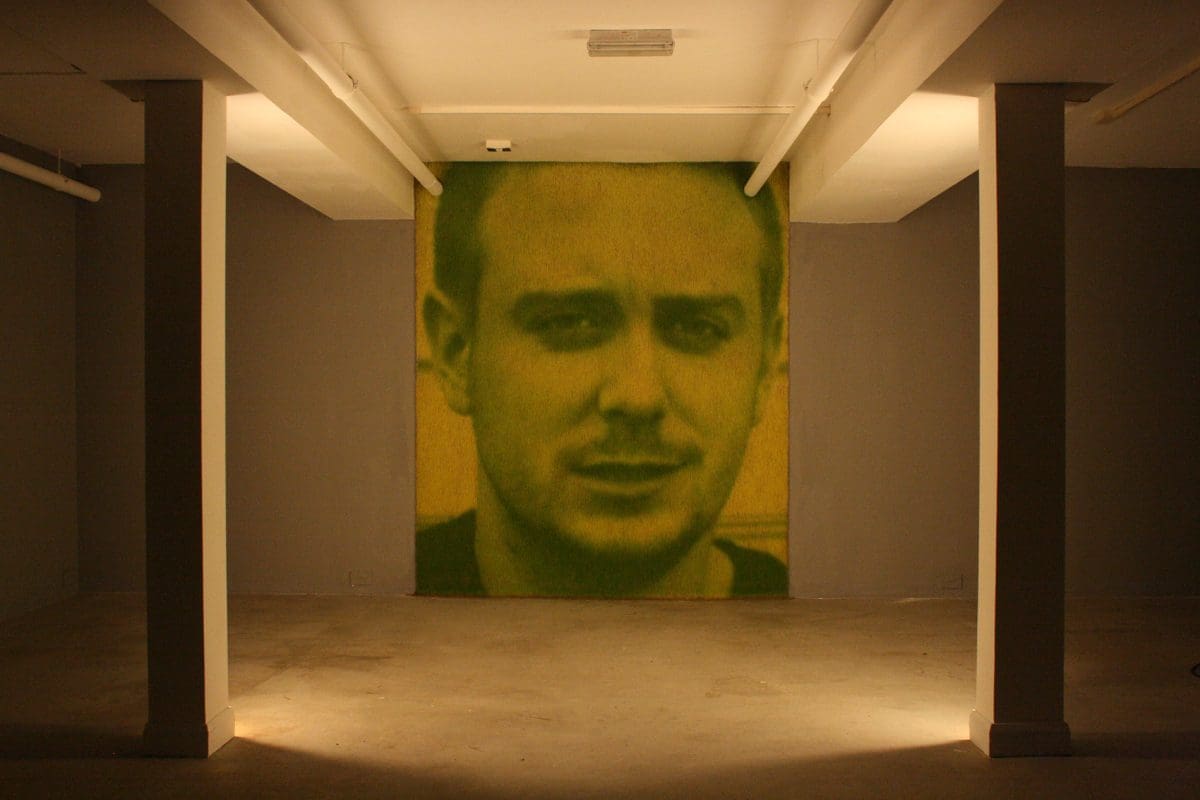

When the pair first collaborated in 1990, they each had been working independently with grass— but together they went to a new level as they started deeper scientific research and made chlorophyll “the primary medium that binds us”. They began producing extraordinary realist portraits made of grass. Using grass as a sort of photographic paper, Ackroyd & Harvey stimulate chlorophyll with different light exposures to make it more or less active, fostering a range of tones from dark green to bleached yellow. These tones form the imagery.

For their Biennale project, Ackroyd & Harvey’s large five-metre-high panels of germinated grass seeds—including Indigenous species—will manifest as full-figure portraits, with cutaways of facial close-ups. The people whose faces will feature is a careful selection process: Ackroyd & Harvey say the decision-making will be collaborative, decided when they arrive in Australia to make the portraits.

Harvey describes their grass portraits as being images produced on a molecular level, rather like pixels. “What is lovely about the chlorophyll molecule is that it is exactly the same in structure as the haem molecule in our blood,” he says. “The only difference is that in chlorophyll it has magnesium as a binder at its centre, and in our blood it has iron. Life on this planet is here because plants are able to harness energy from the sun and transform it, which gives us all the foods we have, the atmosphere we breathe. Everything is because of it.”

Both artists have been excited at the prospect of using Indigenous Australian grass seeds in their AGNSW work, with collaborators in New South Wales exploring varieties, germination times, and responses to different light levels. Interactions with the Indigenous-based youth climate network Seed Mob has also informed them of First Nations understandings of environmental issues.

“Grasses are the most successful plant on the surface of the planet,” Ackroyd says. “Rice, corn, barley, wheat . . . and some people would say that humanity is in service to the grasses. Sea grasses and tropical forests have an extraordinary level of carbon dioxide absorption. So, if we put photosynthesis and ecology at the centre of our economy, then we really are shifting the way we perceive our place in the world. It comes down to our relationship with nature: we are part of nature; we are in the web of it. But our systems of economy tend to be around consumption and high levels of industrialised production. All these things need to shift. Chlorophyll is completely life-enhancing.”

When they hear the oft-levelled criticism that art is rarely politically effective, Ackroyd & Harvey aren’t rattled: they point to artist Joseph Beuys, who helped found the German green party Die Grünen, and also created the 7000 Oaks land artwork, in which 7000 oaks were planted in and around Kassel, Germany. One of Ackroyd & Harvey’s ongoing projects is Beuys’ Acorns, in which more than 100 acorns were collected from the Beuys Kassel trees, and then germinated. They are now periodically displayed as a living installation.

“Beuys was putting ecology, education and collectives at the heart of things,” Ackroyd says. “That was a catalyst for us to go and get the acorns.”

Ackroyd & Harvey

Art Gallery of New South Wales

12 March—13 June

This article was originally published in the March/April 2022 print edition of Art Guide Australia.