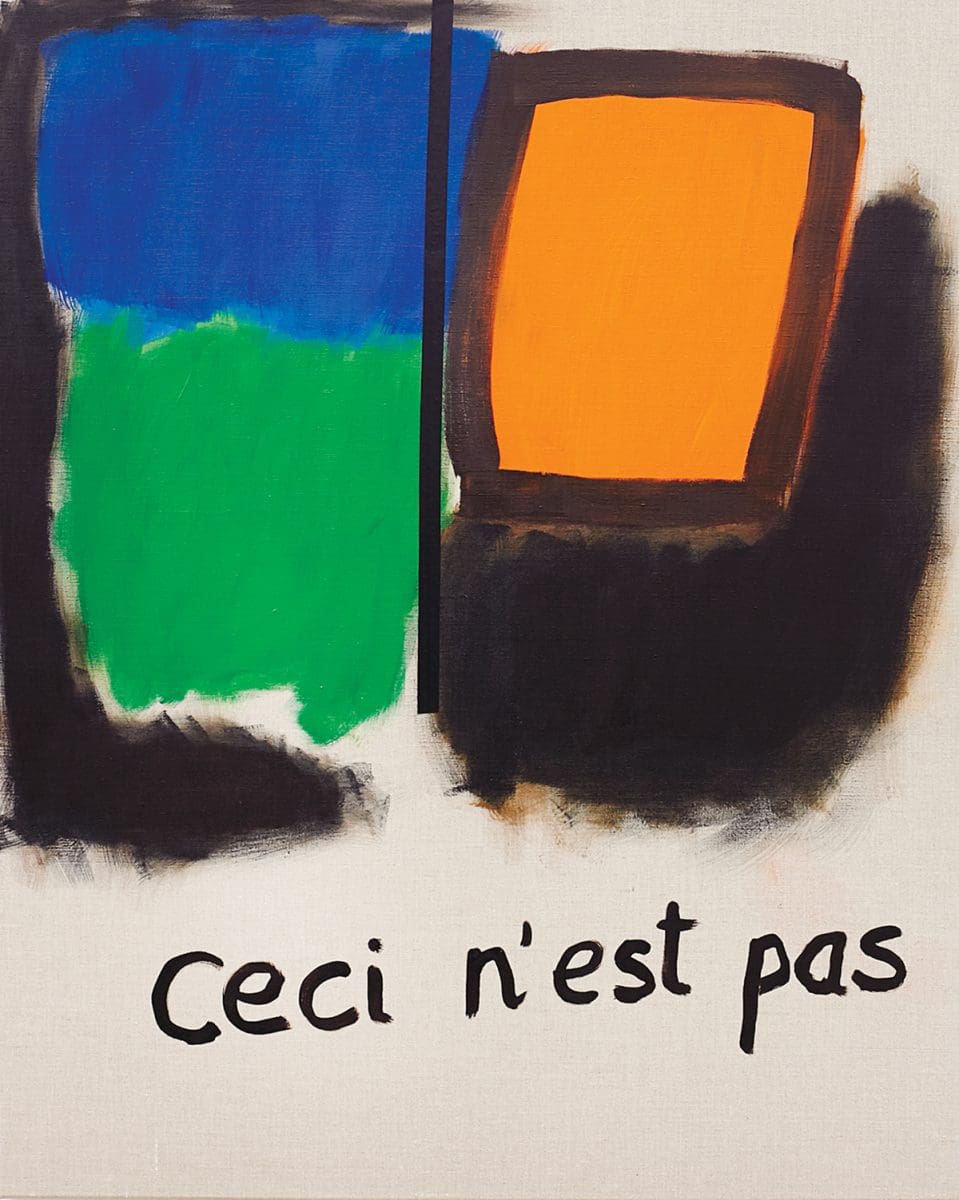

“I like to end a bit before the end,” Newman says. “I like to leave things a bit undone. There’s a question hanging there. In a way, the question is, is this a painting? How much do you need for it to be a painting? Is one stroke enough? A blob?”

This is no neutral act. In these uncertain times, art has tended to respond with certainty. We live in an age of statements, positions, artists tied to the masts of ideas. Where Newman offers questions, many fall back on answers.

If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. And if it is broke, at least acknowledge it. In these broken times, Newman says, “what I’m putting out there is also broken, all bits and pieces”.

To call something broken isn’t necessarily to imply it doesn’t function. In fact, the very brokenness in Newman’s paintings renders them nimble when it comes to conveying a sense of subjectivity.

One can even notice a slight emotional shift among the paintings in the Neon Parc exhibition, between those made in 2015 and those made in 2016, before an Australia Council Cité Internationale des Arts residency in Paris and afterwards.

On Newman’s return from the residency, she felt more emotionally open. Looking back at the paintings she made before Paris, she found them “uptight”. The ones that follow are rougher, even more unfinished.

But all of them have something in common: nothing. “Whenever I paint,” Newman says, “I paint about nothing – I just paint about painting.”

In an essay for Newman’s 2013 monograph More than what there is, Damiano Bertoli took it one step further, describing her practice as a “reflexive catalogue of meta-painting: paintings of other paintings, paintings about paintings, paintings about paint, and its absence. Paintings and not; images, objects and arrangements that inhabit the psychic space elaborated by the history of painting and its capacity to activate the human ‘subject’, with or without pigment, or application.”

From time to time, Newman has turned to other mediums including installation, collage, text work, photography and sculpture – mediums, she says, she’s “not very good at”, the idea being to “find that thing in there that’s me”.

Over the past few years, she has returned to pure painting, a throwback to something simple, from an earlier period of her life, when she first began to make art. “It’s the most basic kind of art making,” she says. “Painting is unpretentious in that way.”

Even so, it isn’t without its difficulties. “I always feel like an amateur,” Newman says “I always feel like I don’t know how to paint.”

Just as she was told more than 30 years ago that she couldn’t draw, it’s safe to say that Newman can’t paint – and it’s a very good thing she can’t.