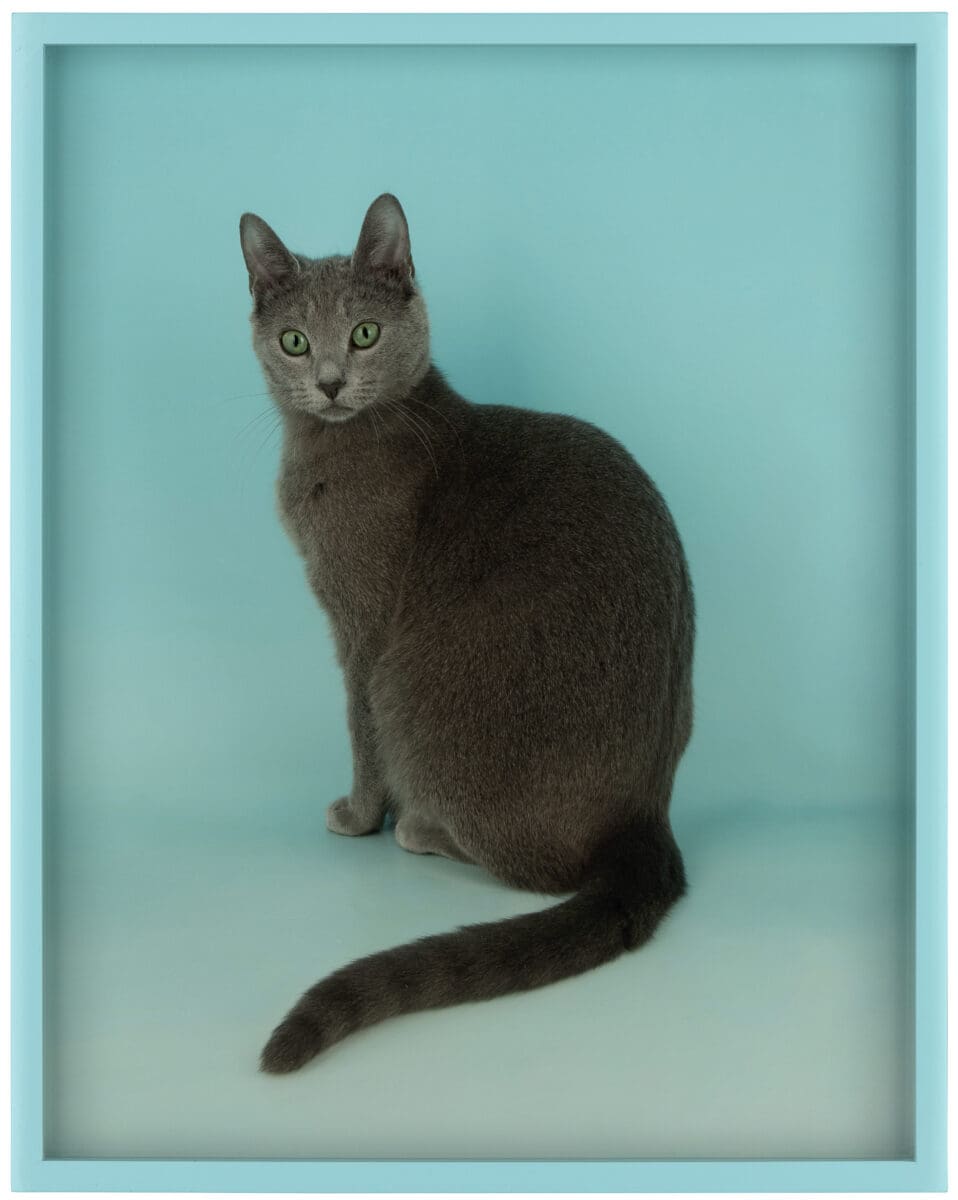

There is a small creature who lives in my house. I care for him daily: food morning and night, water, medication, litter, play. I know him more intimately than anyone else in the world, yet we don’t speak the same language. Sometimes his yowling frustrates me: what does that mean, I ask, and he yowls back, as though that answers the question. It does. It doesn’t.

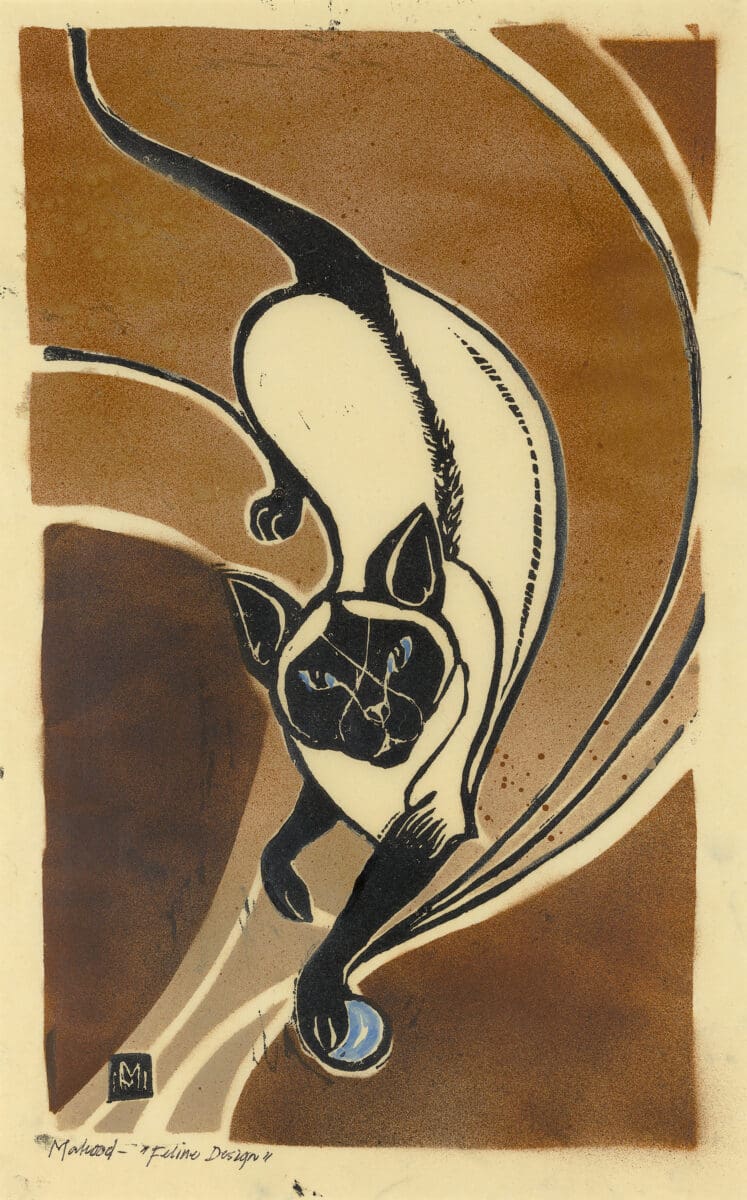

I wonder if, in another life, he would have been something else. His life as we both know it now is a pattern that goes, predictably, as such: eat, sleep, play, sleep, eat, sleep. But there is a wildness in him, some-times: the pattern can be interspersed with random attacks, his pupils dilating, his claws appearing like weapons. I wonder if he thinks I am prey, or if he doesn’t think of me very much at all.

There are moments of peace: me lying on my bed, staring at the ceiling, or reading, or watching TV, his full weight on my chest as he purrs and licks himself clean. Or me doing anything, really, and him just being there. It’s clearly an experience that has existed for as long as humans and cats have shared a domestic space, no matter the cultural context. In Ishikawa Toraji’s 1934 colour woodblock Leisure time, a fully nude woman sits and reads a magazine; her skin rubs against a calico cat, who faces the other way, similarly comfortable. It’s an intimate, familiar scene; there is no need for language.

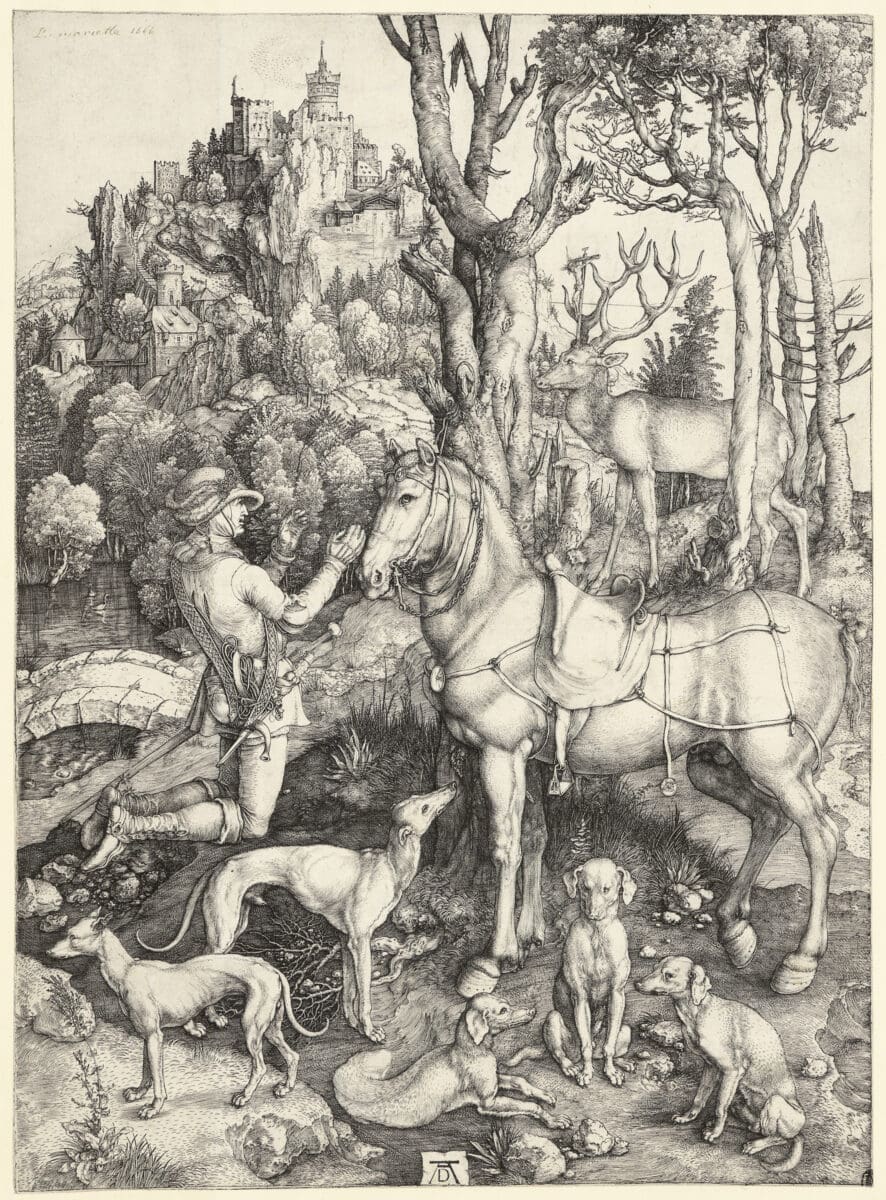

There are moments of violence. When I first adopted him, more than a decade ago, I quickly became afraid of him, his unpredictability. I would sometimes hide in my room, crying, unsure of how to help him or myself. Scratch marks flowed like red rivers down my neck. I laugh with bewildered recognition at Richard Bosman’s sugar lift etching Revenge of the Cat (1983), a two-panel work. In the first, a man holds his hand up to a cat who looks poised to strike. It’s futile, of course: in the second, the animal is in motion, teeth bared, as the man turns away in fear. The streaks on his cheek match his body and the windows; are they tears, or just patterns?

There are moments of observation, mostly from a distance, sometimes completely undetected. I wonder how many times he can see me when I can’t see him, when his big eyes glow in the dark and stare at me. Or when he is asleep, and I gaze upon him like a detailed work of art. We live on the first floor of an apartment facing a main street, and my sister says her dream is to drive past and see him on the balcony, like those cats who live in terrace houses and sit at the window, looking out at the world. John Williams’ silver photograph Untitled (1974) reminds me of this: three little fuzzy faces in a window, though it’s not clear if I’m looking in at them, or they are looking out at me. Or in mutually observing one another, are we both seeing something different from each vantage point?

When I ask the question of another life for my cat, what he would or could have been, what I mean is complex and ultimately unknowable. Would he have been a working cat, if I was a working woman in that way: a little assistant at my feet while I physically toiled all day? Or, if cats had never been domesticated in the way they are, would he have had his own life somewhere outside of here, walking the streets and the greenery with no agenda, no plan, just a cat and the big, wide world? Or would he not have existed at all, outside of this?

I care for him as I would for the biological children I have decided I will most likely not have; in turn, he cares for me in his own way, simply by being there and both witnessing and experiencing our small domestic world together. It is a symbiotic relationship that I suspect is becoming increasingly important as every-thing else in the world splinters, wars rage, screens explode with cheap imitations of real life.

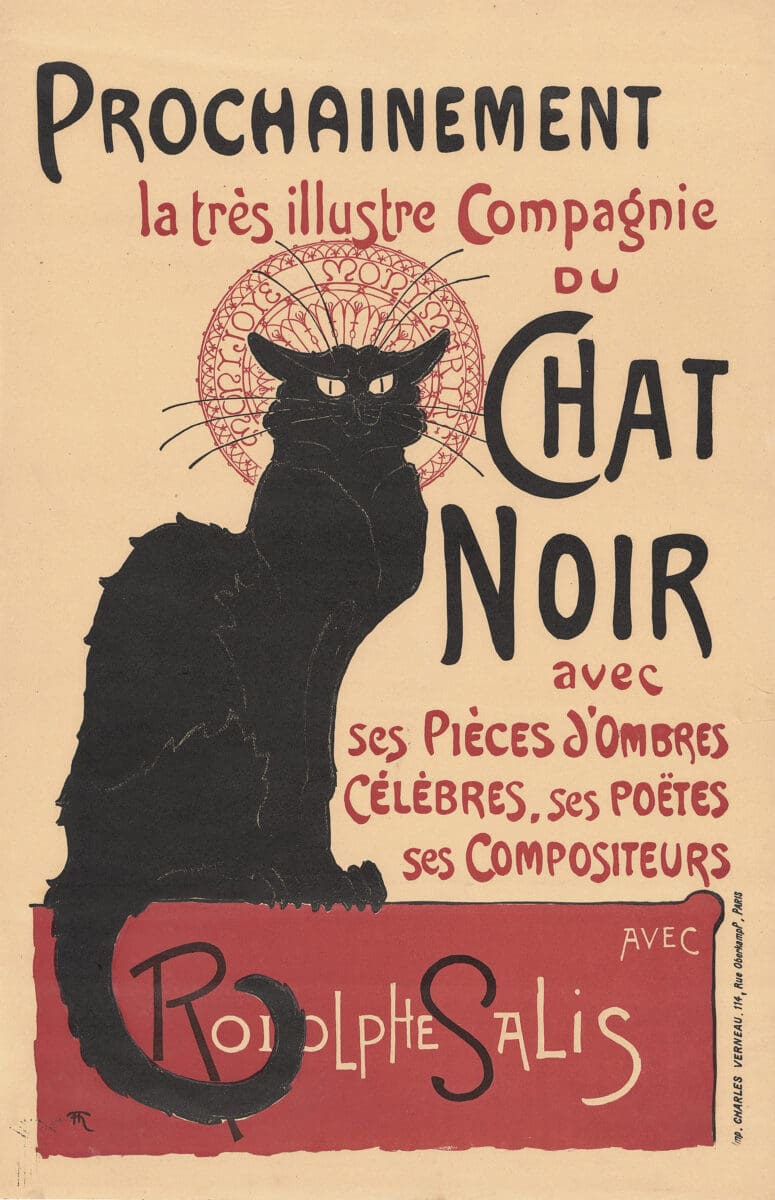

Yet the strangeness never quite dissipates. Near the end of the exhibition, my eye is caught by something moving, and I startle when I turn around and see a black cat waving at me, its paw up, down, up, down, up, down, up, down. Greatest Hits Untitled (2012) installs electronic components into a real, taxi-dermied cat so that it is stuck in this state of unreality forever: up, down, up, down, up. I think I’m at peace with my relationship with my cat one day becoming a memory, rather than subjecting him to a fate like that. He is not human, but he brings out the humanity in me.

Cats & Dogs

National Gallery of Victoria —The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia (Melbourne/Naarm)

On now—20 July

This article was originally published in the March/April 2025 print edition of Art Guide Australia.