Despite a successful career spanning 35 years, it’s not easy to see work by the late American artist Mike Kelley in Australia.

Geoff Newton, director of Neon Parc gallery, is a long-time fan of Kelley’s work, and this, combined with the fact that there hasn’t been a significant showing of his work since the 1984 Sydney Biennale, was the impetus behind the solo exhibition, Mike Kelley. It features the 1989 work Pansy Metal/Clovered Hoof and a selection of video works and is a chance for Australian audiences to get acquainted with pivotal works from Kelley’s oeuvre.

When asked why Kelley’s work has been under-exhibited here, Newton says it’s possibly because it’s difficult work. “Not difficult to digest, but hard to access. For Australian institutions, trying to find the right context for them may be hard,” he says.

Kelley was a prolific, multifaceted artist, utilising and creating everything from photography and sculpture to painting, drawing, installation, textiles, performance and video art.

Regardless of the medium, Kelley sharply references, dissects and perverts (often in a self-deprecating manner) complex and sometimes disparate themes in his work, including: sexuality, perceived normality, class, gender, youth, rebellion, memory, popular culture and counterculture.

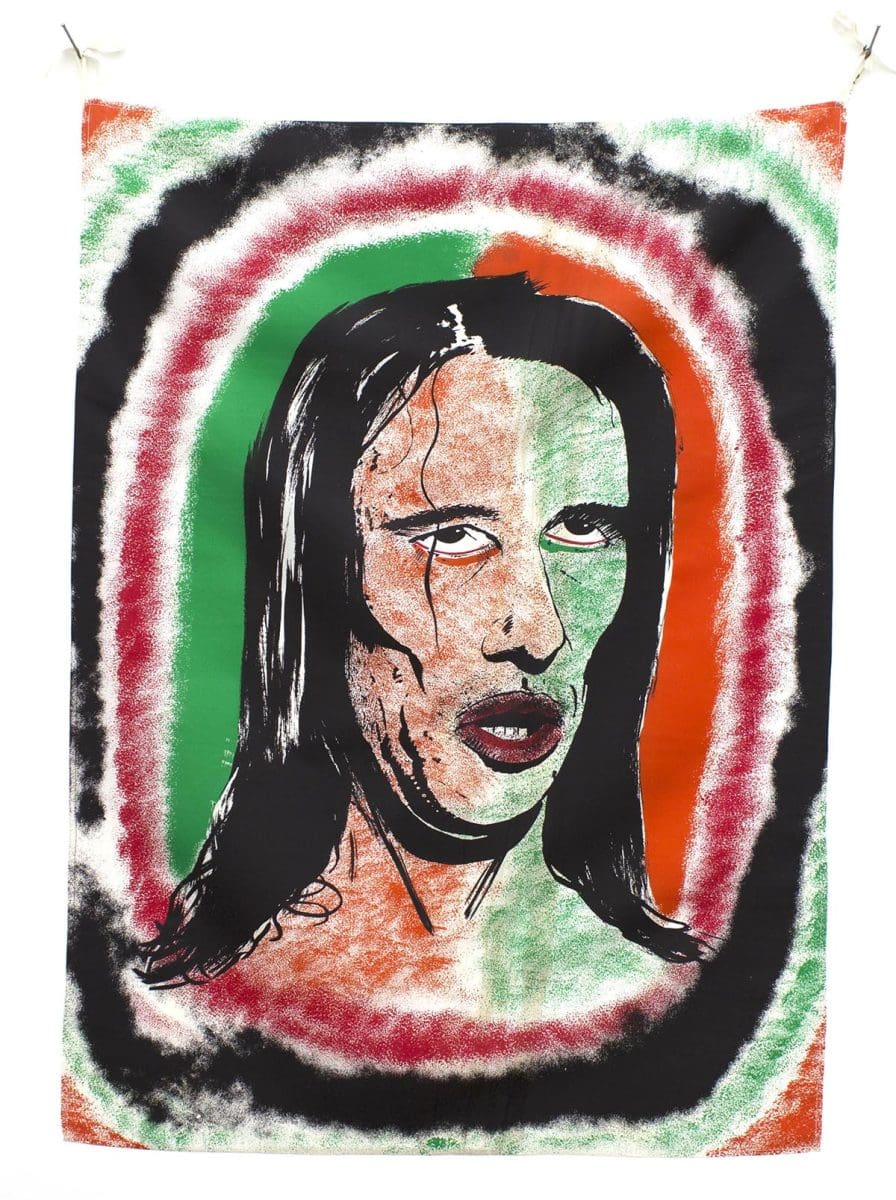

The 10 oversized silk banners that make up Pansy Metal/Clovered Hoof are full of attitude and certainly touch on some of the above. They feature rudimentary but iconic and instantly recognisable imagery, which he used to reference and lampoon not just heavy metal culture, specifically the band Motörhead, but also history, male sexuality and high school culture (a recurring motif throughout his career).

Kelley often drew upon his own history and experiences for his work, and he certainly didn’t spare himself in this instance. Most noticeably, perhaps, is the fact that his name features on one of the banners in signature Motörhead font, umlaut and all. The title of the work and his use of clover imagery references another aspect of his life: his Irish-American heritage.

The banners were originally created as costume pieces for a 1989 performance piece, a collaboration between Kelley and dancer/choreographer Anita Pace which was set to a soundtrack of Motörhead tunes.

Performance and video art were a big part of Kelley’s diverse practice, and the inclusion of five of his low-budget video-based works from the 1980s paints a fuller picture, providing a “broader context to his work and career,” Newton says. With the exception of The Banana Man, they are collaborative works, created with his peers and friends, including Paul McCarthy and Raymond Pettibon. “They’re a dialogue,” Newton says, an insight into the LA art scene then, a crucial period in Kelley’s career and contemporary American art history.

Alhough not part of the exhibition, a screening of Kelley’s genre-defying feature-length musical, Day is Done,2005–06, is slated for 10 December. It’s one of his later works that shows that Kelley continually turned to youth culture and experience for inspiration. Day is Done is based on a series of high school yearbook photographs depicting extracurricular activities such as plays, holiday festivities and hazing rituals that come to life in 32 video chapters. Kelley describes these as “socially accepted rituals of deviance.”

To honour Kelley’s practice and spirit, Neon Parc have organised a performance program to accompany the exhibition, featuring performances by musician and filmmaker Philip Brophy on 5 November and Sydney avant-noise band Menstruation Sisters on 19 November.

Mike Kelley

Neon Parc: Brunswick

October 28 – December 17