Assembled from the Museum of Brisbane collection and significant loans, New Woman chronicles 100 years of female artists in Brisbane. This story features 111 artworks and begins in an era of rigid social codes around pay, status and creative identity which a century-long succession of women overhauled, revealing ever-greater artistic self-determination and opportunity.

The press nickname ‘new woman’ was coined for 19th-century English editor Ella Hepworth Dixon, following the publication of her 1894 novel The Story of a Modern Woman. “It described a kind of womanhood that was only newly possible,” explains curator Miranda Hine. “Someone independent and unconfined by domesticity. A public person.”

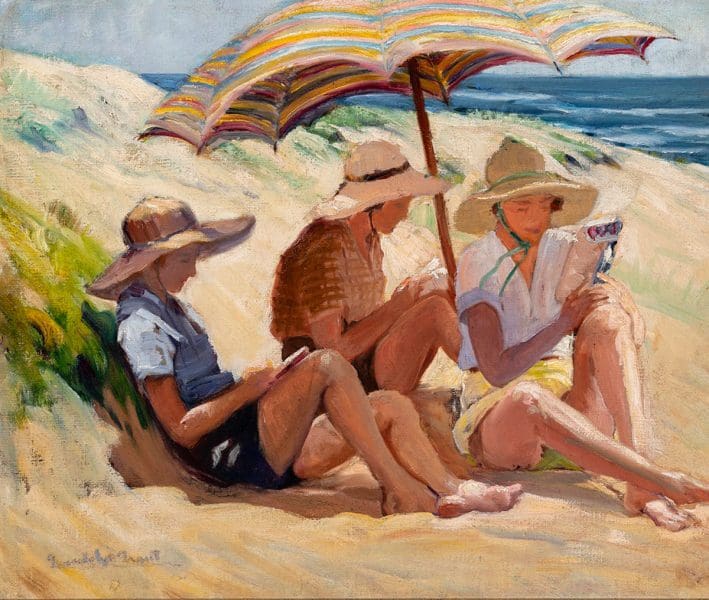

In 1920s Brisbane the consummate new women were career artists Vida Lahey and Daphne Mayo. They devoted themselves to developing the health, longevity and civic esteem of the arts in their city. “It was a pivotal era,” says Hine. “Mayo and Lahey acted on the belief that art was for everybody.” They raised donations, headhunted acquisitions for Queensland Art Gallery, sewed storeroom curtains, established an art reference library, organised children’s art classes and inaugurated travel scholarships. The institutions they founded still shape art making in Brisbane.

The Brisbane art world spent the early 20th century in self-invention, establishing schools, collectives, studios and local stylistic doctrine. Then suddenly it was the 1960s: broadcast entertainment, consumerism, counterculture and international travel exploded across the city. Any sense of isolation dissipated. As Hines says, “Women travelled overseas, feeding ideas back home. Brisbane embraced abstraction, albeit unfashionably late, and began to develop its own voice and style in reply to international movements.”

By the 1970s and 1980s wanderlust gave way to a phenomenon familiar in many Australian cities: exodus. Artists upped sticks in droves. A resolute few remained to uphold a much smaller community and withstand the cultural disinterest of Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s premiership (1968-1987). “There was virtually no support for the arts at this time,” explains Hine. Unchecked by institutional convention, ephemerality and material experimentation surged, and disused spaces were repurposed as galleries. “The legacy of that DIY attitude endures in the strength of Brisbane’s contemporary ARI scene.”

Any historic collection of art by women will contain silences and misattributions. Take a 1921 coffee service made in the Lewis J Harvey School workshop, for instance. It was made by Sarah Ellen Bott and is “a beautiful example of an exercise Harvey facilitated,” says Hine. “Such works are usually associated with his name, not the (often female) artists who made them.”

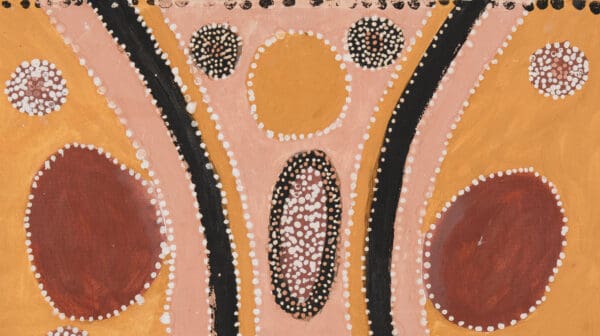

There are also missing chapters: “We don’t have a single work by a female Aboriginal artist preceding 1950. It’s a huge setback in recognition and history.” For Hine, a corner was turned with Tracey Moffatt’s Something More photographs, 1989. “The work was made at a moment when Aboriginal women were taking the lead, becoming recognized here and internationally for their sophisticated, powerful and political explorations of female Aboriginal identity.”

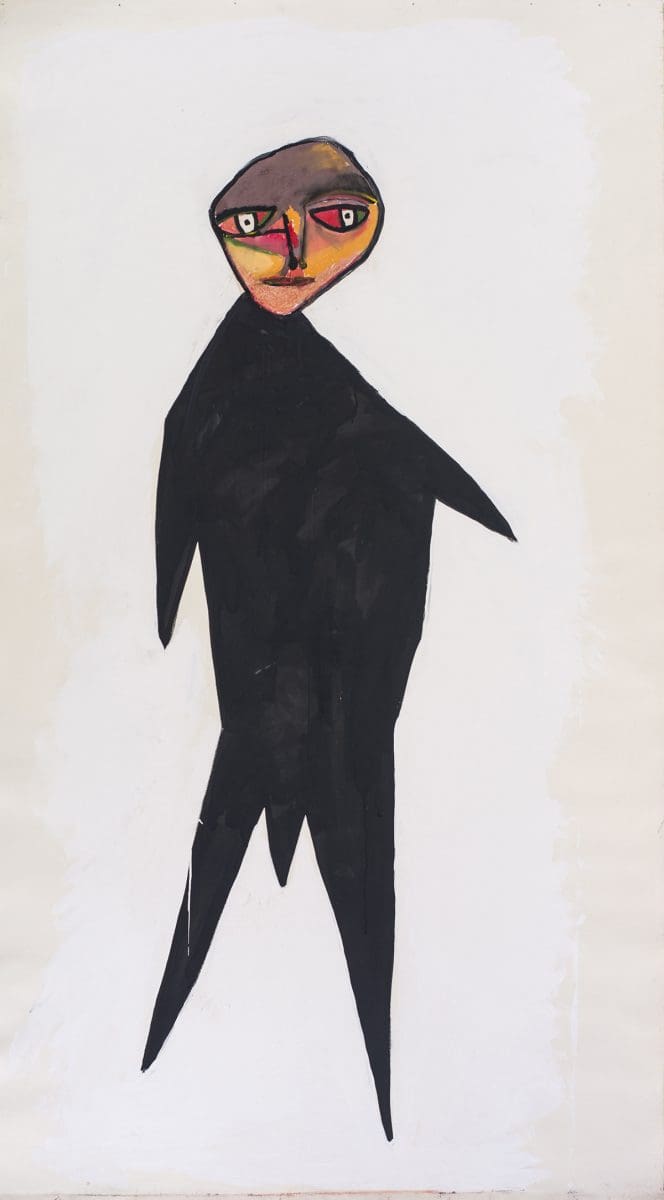

Expressions of womanhood in the first-person permeate the exhibition. Dana Laurie’s soft-toned paintings feature the artist’s likeness, staring through a painterly haze. James Barth’s staged self-portraits wonder how trans bodies might occupy new space in a history of female models.

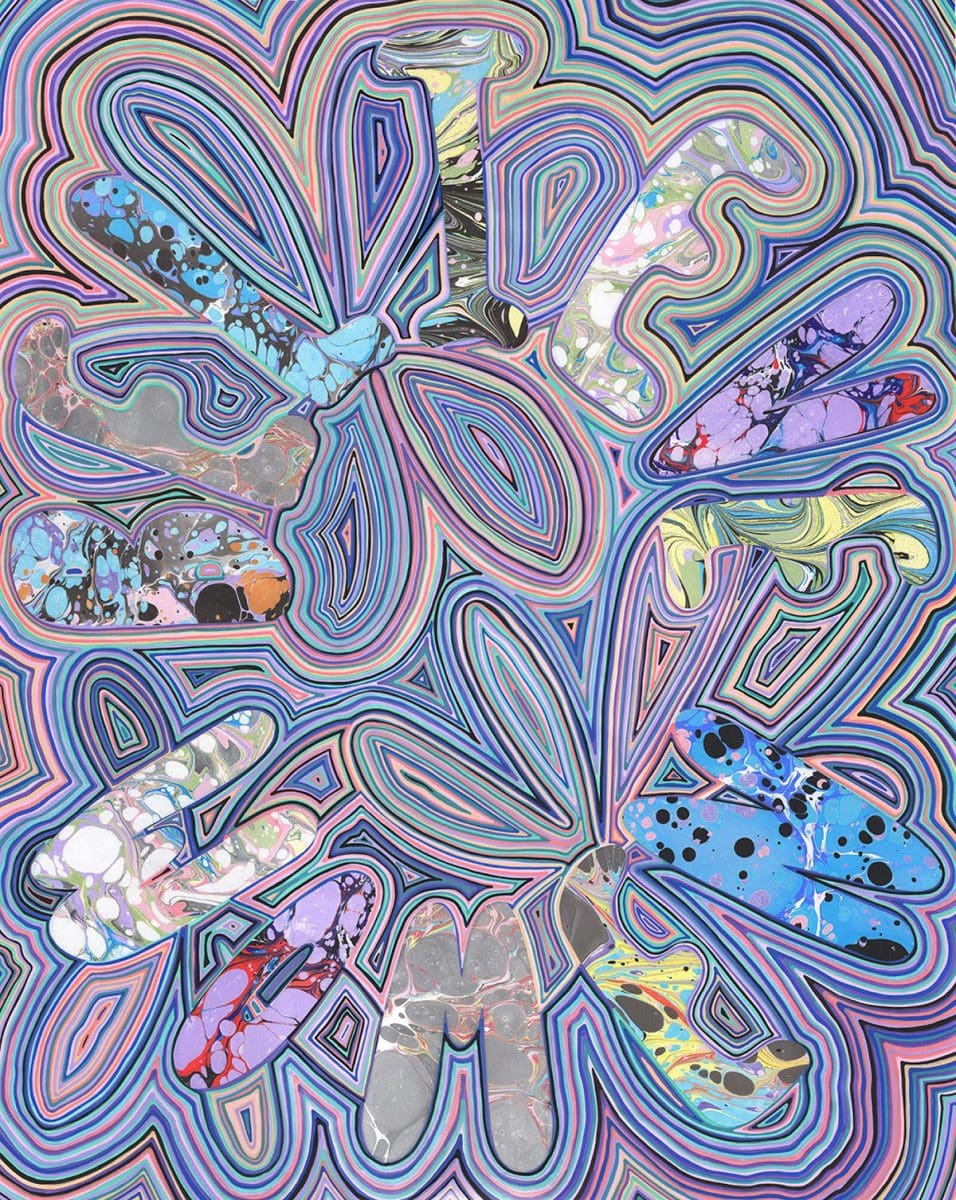

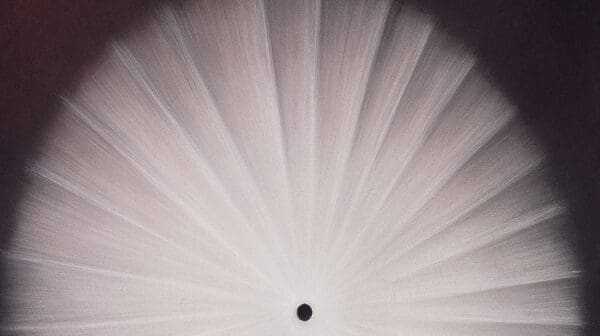

The epilogue of New Woman is a fresh commission: an immersive three-wall painting by Emma Coulter. Piquant columns of primary-ish colour radiate from a central point. “The painting doesn’t submit to the room,” says Hine. “We step into the painting.”

New Woman

Museum of Brisbane

13 September – 15 March 2020