There’s no denying the urgency of the world we live in. The news seems increasingly bleak, the climate is changing, and social media churns out absurdity by the screenful. But that’s never the whole story of our lives: we eat, garden, work, listen to music, make art, watch TV, and crack up laughing with friends.

For curator Hannah Presley, these seemingly unremarkable joys are not just worth examining – they are crucial to presenting a rounded narrative of Aboriginal experience.

Presley’s latest exhibition, A Lightness of Spirit is the Measure of Happiness at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, foregrounds food, music, films, friendship, cups of tea – the things of daily life in Aboriginal culture. Featuring ten new commissions, it’s a deliberate shift in focus from the current artistic landscape, in which contemporary Indigenous exhibitions are so often steeped in trauma and shrouded in educational strategies.

“The reality is,” Presley says, “if I’m in the throes of install, and I’m opening an artwork and it’s a massacre map or something that is very important and heavy, there are times when I think I would rather see a smiling camel!”

We both burst out laughing.

Running through the exhibition is what Presley calls “cheekiness” – a sense of humour that she describes as “a vital tool in Aboriginal culture, to deal with all the injustice and all the heavy history.”

From striking paintings of pop icons to a spaghetti western shot in the Central Desert, it’s a lively and joyous survey of contemporary Indigenous work.

A Lightness of Spirit is the Measure of Happiness is a significant exhibition in a number of ways. Presley is the first Aboriginal curator to work at ACCA in a permanent role. And as she points out, prior to the “extraordinary” 2016 exhibition Sovereignty, curated by Paola Balla, no ACCA show had focused on Aboriginal artists or curators since 1994.

Seeking to address this serious absence, the Yalingwa initiative is a significant new partnership between ACCA and TarraWarra Museum of Art which will see three curators appointed across the two institutions, resulting in three major exhibitions. A driving force of Aboriginal artistic and curatorial voices, there’s a focus on commissioning new works and showcasing artists from the south-east.

Presley is the first curator to take up the reins.

“There is a bit of a responsibility being in ACCA and being an Aboriginal curator,” she says, emphasising that making the show accessible was a key concern.

“Keeping in mind that ACCA is such an important space, I liked the idea of the Aboriginal community coming in, feeling safe to come in, and then seeing the work and seeing themselves reflected in a positive light – that was really important to me.”

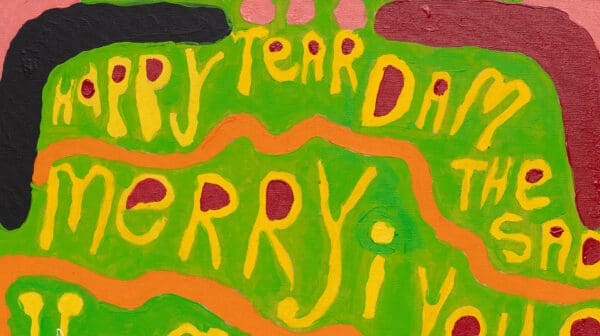

One artist whose work exuberantly embodies the show’s ethos is Kaylene Whiskey. Hailing from Indulkana, a remote community on South Australia’s Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands, Whiskey – who Presley calls a “superstar” – recently shot to national attention after winning the prestigious Sulman Prize. Her bold, detailed work folds her favourite musicians and comic book characters into scenes of everyday life in Indulkana. In the winning Sulman Prize painting, Kaylene TV, Cher and Dolly Parton hang out together in a living room with a skateboard, boomerangs, a Christmas tree and a mingkulpa (local tobacco plant). Other paintings see Wonder Woman in the act of lassoing a kangaroo; Whoopi Goldberg flying kites; Michael Jackson moon-walking against a field of dot patterns that could be either disco lights or traditional designs, or both.

“There’s no escaping what’s happening in pop culture,” Presley says, highlighting the importance of reminding people that Aboriginal art made now is, by definition, contemporary.

We all have shared cultural references, and “everybody loves Michael Jackson.”

Another rising star from the Indulkana community is Vincent Namatjira, whose distorted, expressive portraits of politicians and world leaders have achieved growing international acclaim. His new paintings for the exhibition will see these figures – including Donald Trump – placed within community contexts.

“It feels really cheeky, it has humour,” Presley says of Namatjira’s work, “but it’s also based on this idea that there’s all these politicians in Australia and elsewhere that are making decisions for his community and his life. He’s trying to bring them into the community and work out where they fit, make them known to everybody.”

Other artists, like Yhonnie Scarce – who Presley describes as “extraordinary” – examine history as inextricably intertwined with their being. Scarce’s work for the exhibition sees photographs of her great-grand-parents printed on fabric, and adorned with the delicate blown glass for which the artist is renowned. Lisa Waup’s sculptures draw on her engagement with weaving as a traditional and contemporary form, while Peter Waples-Crowe explores his emerging role as a queer elder in the Aboriginal community.

Presley emphasises that the exhibition, while celebrating the quotidian, certainly doesn’t ignore the effects of colonisation and injustice on First Nations people.

“There’s no avoiding these issues – they come with our everyday experience,” she says. It’s important for Presley, however, that the first encounter of the work is a positive one.

“Because that’s part of our everyday as well, you know – we fight for that. That keeps us going.”

Bringing together a stellar selection of artists, this exhibition addresses history and culture through an experience of joy. It’s a deeply important premise – and one that should certainly lighten all of our spirits.