Shinrin-yoku is the Japanese term for forest bathing—a practice where one immerses in nature as a form of self-care. The key is mindfulness, to connect deeply on all sensory levels with the natural world.

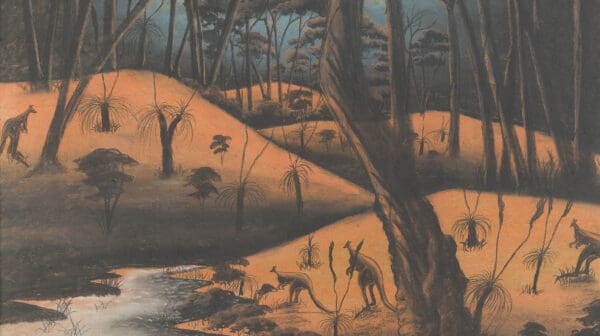

In a sense, shinrin-yoku relates to the idea behind Material Nature—an exhibition of artists who engage with nature through their creative practice. Curated by Dr Anne-Marie Jean, the show brings together the work of Ros Auld, Manini Gumana, Jahnne Pasco-White, John Peart, Ana Pollak, Annika Romeyn, Garawan Wanambi and Savanhdary Vongpoothorn. “In curating the show I’ve asked how contemporary artists are articulating their complex physical and cultural relationships to the environments they engage with, and how the material structures of their works invite us as viewers to consider our own intimate relationships to the material wonders of the natural world,” Jean explains.

Reflecting on the physical process of making, Jean says sculptural ceramicist Ros Auld expresses her lived interaction with nature through the application of surface textures and glazes onto her abstract forms. Describing the first time she saw Auld’s ceramic work, Landform (2011), during a studio visit, Jean says, “I had a sense of Ros arching and stretching to hold its prominent form and weight, supporting its infrastructure with her torso, with her own trunk. This piece stimulates the viewer into the physical experience of making, as much as its connection to the materiality of nature, and representation of it.”

Taking a different approach, Jahnne Pasco-White allows the domestic world to infiltrate her painting practice. In a room-sized installation created specifically for the exhibition, large sheets of canvas and fabric encompass the gallery space, hanging from the ceiling and draped over multiple surfaces. Marked with a soft palette of warm flesh-coloured dyes, a defining feature of Pasco-White’s work is the inclusion of everyday materials and occurrences—marks made by her child and dyes and inks made from organic matter and human debris. As Jean explains, “The works are skins and stains of nature, and human commingling with them, lifted from the horizontal plane to hover in bodily relation with a moving audience.”

During the development phase of the exhibition, Jean traveled to north-east Arnhem Land to visit Manini Gumana, a Yolŋu artist who lives and works from her homeland, Gängan. Her chosen materials are bark, stringybark poles (Larrakitj) and pigments she sources on Country. Painting directly onto the Larrakitj and sheets of bark, Gumana creates highly detailed images that symbolise patterns made by the ocean and the life it contains. While there, Jean also met Gumana’s husband, Garawan Wanambi. Using similar materials, his work depicts rivers, waterways and the mosquito. “Like all Yolŋu paintings, their work is interwoven with multiple meanings,” says Jean. “For me, the linking feature is the physicality of pressure and release in their mark making.”

Another artist working with wood is Ana Pollak. Living on Dangar Island on the Hawkesbury River, the ebb and flow of the water environment is a key experience in Pollak’s daily life. Transferring this into the work she creates, Pollak carves into slabs of blackbutt wood before painting pale hues onto the rippling surfaces. “She describes this series of wooden reliefs as being about the earth’s ancient skin shaped by water and wind and the man-made scars on its surface,” Jean explains. “She’s carved into these beautiful blocks of wood and used clay wash on them in the same way that she uses clay wash and ink on her paintings.”

Connecting to the exhibition title, the materiality of John Peart’s collages has always interested Jean. Drawn to the tactile process of tearing and placing strips of paper onto another surface, Peart worked with his materials to evoke the negative spaces within condensed bushland. “His mark making is densely layered and woven, so when these rough-edged, firmly articulated dots of muddy and vibrant colours layer up on the surface, they echo a living environment of growth, movement and light. Our position as viewers then is from within.”

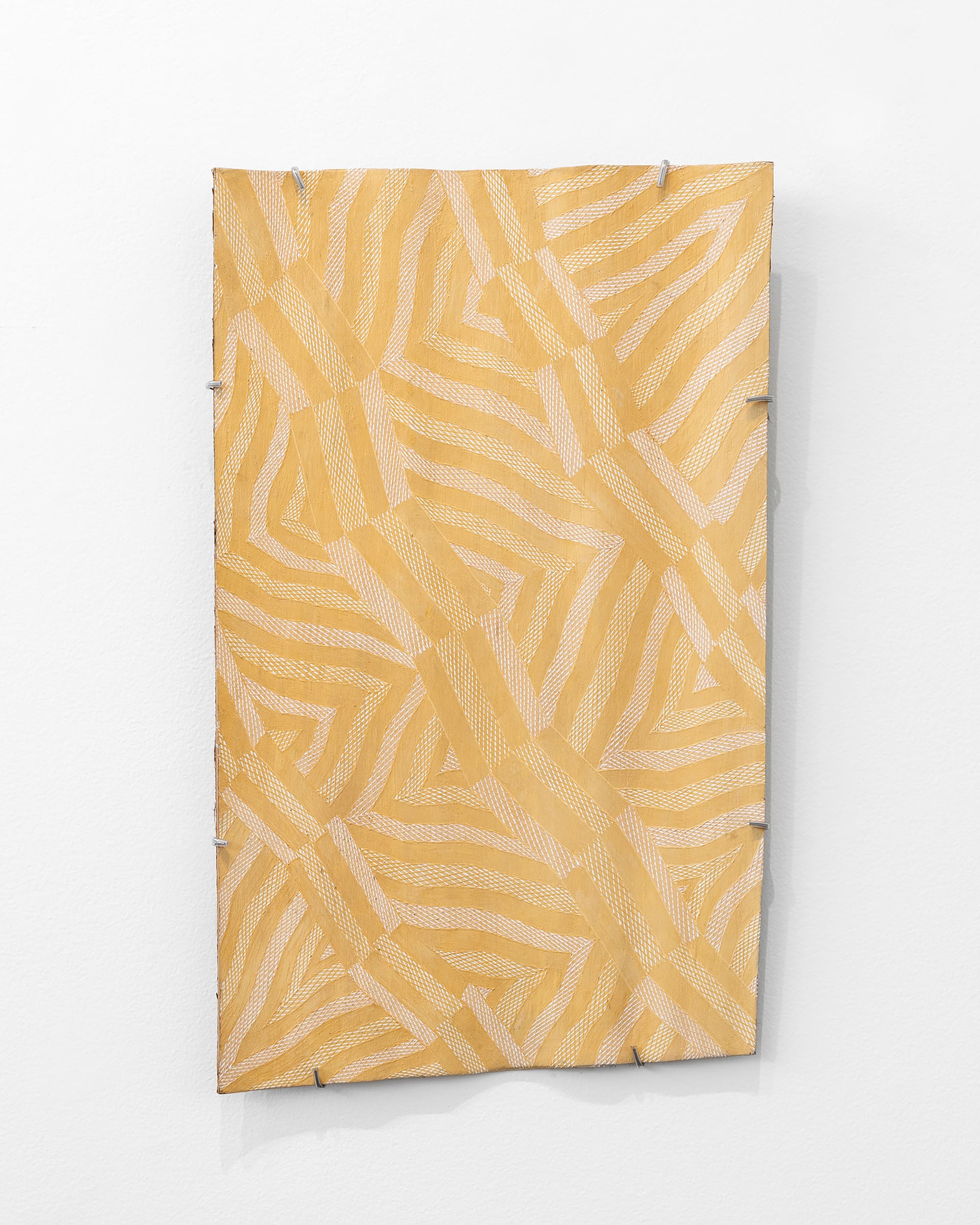

Similarly, Savanhdary Vongpoothorn captures light and the patterns of nature through the perforations she makes across her canvas before applying paint. As Jean points out, “There’s a relationship of repetitive mark making and colour that creates a delicate, all-over sensation of being engulfed. There’s no horizon. It’s the most abstract work in Material Nature as it illustrates the non-visual experiences of being in the bush. Like sound and perception.” In contrast, Annika Romeyn brings her physical experiences of trekking and rafting through immense rock formations and waterways in national parks, into her series of intricately detailed watercolours of the landscape.

The result of a long-held fascination with multisensory art practices and how our relationship to nature can inform how we engage creatively, Jean hopes Material Nature will inspire viewers to think deeply about the human connection to the natural world. “I wanted something quite broad, but a lot of the show is about breaking illusion and reconnecting the viewer personally with the materiality of nature. As our bodies respond to the works and their compositions, we have remembered sensations, sensing if not seeing, the proximity of foliage, the wet damp soil, the rough bark, the radiant heat, the water and the rain.”

Material Nature

Drill Hall Gallery

(Canberra/Ngambri ACT)

20 June—10 August

This article was originally published in the May/June 2025 print edition of Art Guide Australia.