Tearing down the mythologies of the Western cultural canon for her latest paintings, Filipina Australian artist Marikit Santiago has reversed gender and racial roles, bestowing her female subjects with agency. “It’s important to show a woman of colour in a position of sexual dominance,” she says.

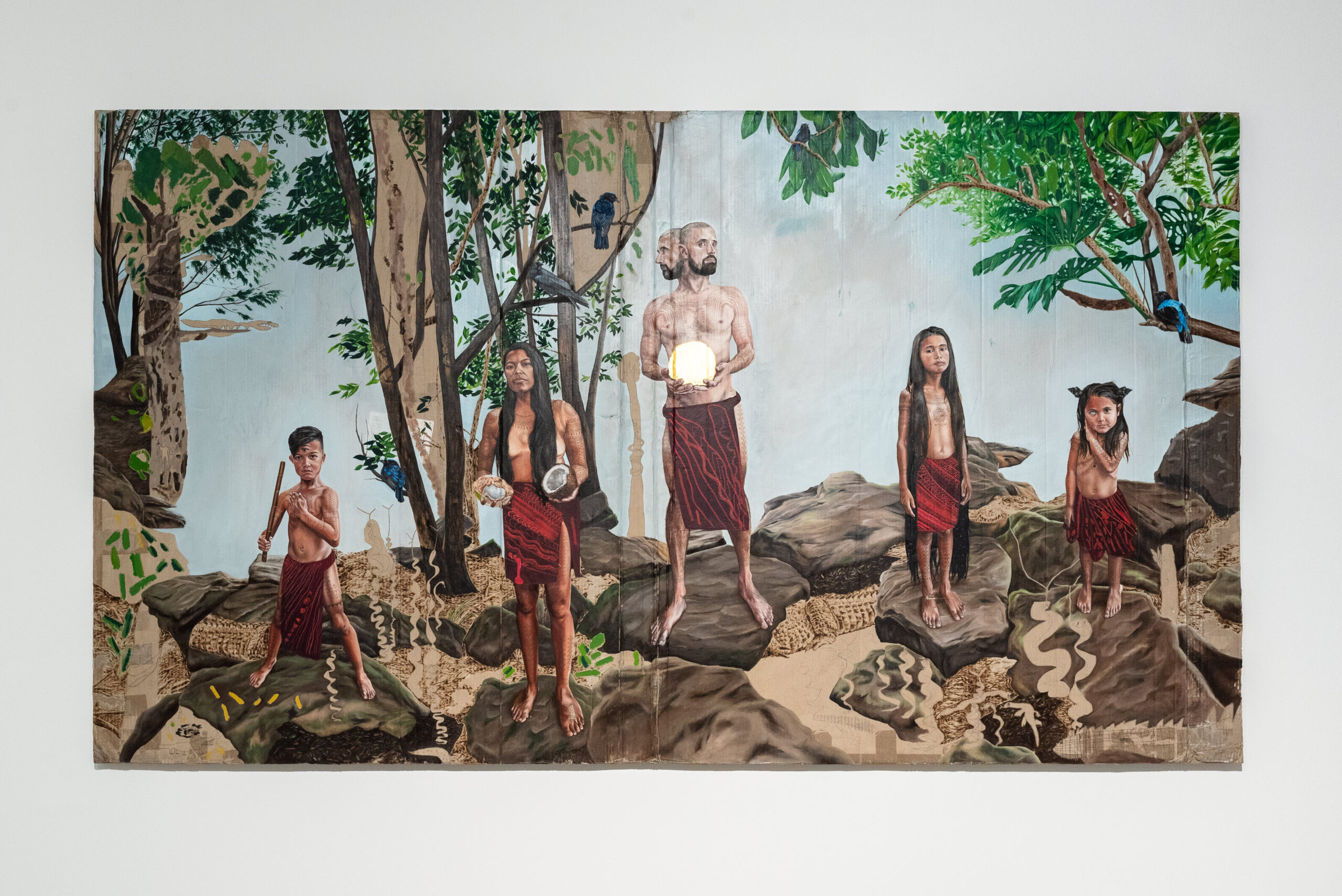

Santiago is standing by her acrylic painting Bathala and Diyan Masalanta (2024) at Campbelltown Arts Centre, for which her husband Shawn Pearl poses as Bathala, the creator god in the Tagalog culture of the Philippines. The artist herself is depicted as Diyan, goddess of love and guardian of ancestral wisdom. Diyan, almost astride Bathala, holds an apple, a hint of the Biblical creation story (Melbourne-born Santiago is Catholic) and looks confidently back at the viewer.

Santiago “went shopping” through European artworks at the Art Gallery of NSW, flipping historical biases for her new exhibition Proclaim your death! The Bathala and Diyan work references French artist Jacques Blanchard’s Mars and the vestal virgin (1637-38), depicting a moment when the god Mars chances upon a virgin asleep in the woods. He will rape her, and she will conceive twins Romulus and Remus, founders of Rome.

Mars and vestal virgin represents “a brief moment just before sexual violence is about to occur”, says Santiago. “We can accept the painting and appreciate its value in art history, but then my work is a subversion of those ideas, where the woman of colour is in a position of power and a moment of pleasure is about to occur. Some people might find that more offensive [than the Blanchard painting]; I find that [reaction] very interesting.”

Another of the five European master works Santiago reimagines is Italian artist Niccolò Cecconi’s Pompeian bath, circa 1890, which shows white women of nobility washing themselves. “In the background, there is a woman of colour, who is clearly the slave. She was gathering all the garments to wash, probably. She was the only one who wasn’t in some form of undress … [the bathing was] an excuse for the artist to depict some scantily clad women without looking too much like a pervert, I guess, back in the day.”

In Santiago’s reimagined oil and pen take, Pinay (2024), five women and girls from her own family replace the original figures, adorned in matrilineal dasters; the traditional house dresses owned by the artist’s nanay (mother) for housework. Again, each subject defiantly gazes back at the viewer. Santiago’s two daughters Maella, 10, and Sarita, 6, are at the top of the work.

Her son Santi, 8, is not depicted, but made markings including the floral designs on the dasters, reinforcing Santiago’s belief feminism is a conversation that boys must have, too. “Asking an eight-year-old boy to draw flowers on a dress, I was prepared to have a discussion with him, but he asked no questions; he was happy to draw the flowers.”

Santiago, who turns 40 this year and last year won the $80,000 La Prairie art award, having also won the Sulman prize in 2020, was warned in her last year of art school by a “respected lecturer and accomplished artist” that it was unsustainable to base her art practice on autobiographical themes. By her own reckoning, however, her career is “almost entirely invested in the autobiographical”.

Yet her work carries multitudes, including commentary on Western cultural biases, religious ideologies, migration and mythology. “I don’t resent that lecturer and they’ve been very supportive of my career since finishing art school,” she says now. “I think what they were trying to say is my work shouldn’t be so specifically autobiographical; it shouldn’t refer to specific events in my lifetime, [but] we all have shared experiences. I know I’m not the only second-generation migrant raised in Western Sydney that feels sensations of displacement and conflict.”

Santiago is best known for oil and acrylic paintings, but for the first time in a gallery setting is exhibiting large-scale cardboard installations and watercolours. In one room, the three-part artwork The Glamour of Evil (2024), is named for the religious rite of a priest asking a congregation if they reject such glamour.

There is a large cardboard church installation, modelled after San Agustin Church in Manila, the oldest baroque church in the Philippines. This model design is largely created by Santiago’s tatay (father), Noy, who is an architect. Both of her parents are depicted on the church doors.

Beyond those doors is a large altar, on which an altar piece shows Santiago herself in character interrogating doctrinal biases against women (Eve, Pandora, Lilith); her three children interacting with animals that are spiritual symbols from Filipino mythology; and husband Shawn Pearl delving into personas Prometheus and Lucifer, recasting them as heroes contributing to human knowledge.

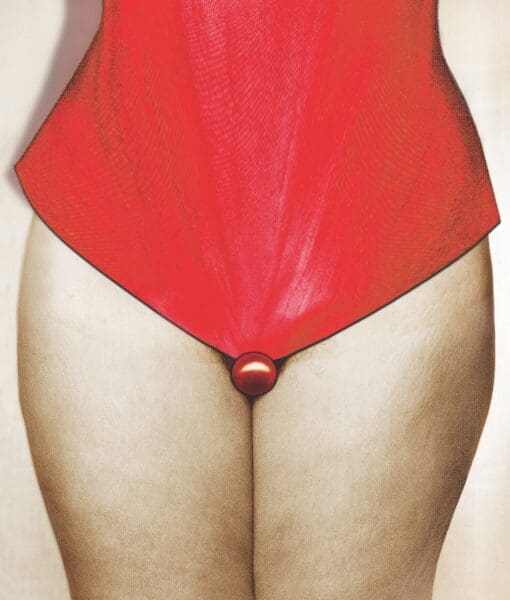

The third part of the artwork is a series of seven watercolours, in which Santiago, draped in red, dances the so-called deadly sins—greed, sloth, lust, pride, envy, gluttony and wrath—in a bid to seduce Pearl, draped in blue, as the virtues. Blue is a symbol of the Virgin Mary, of purity in heaven, while red is a symbol of passion, of God’s blood and sacrifice.

Notably, in the Philippine flag as well, there is a blue band on top and a red band below. “If the flag is flown upside down with the red band on top, it indicates the nation is at a state of war,” notes Santiago.

Spain’s occupation of the Philippines, of course, wrought sustained violence as well as strong Catholicism. When Marikit thinks of the role the Christian churches played in colonisation and destruction of Indigenous cultures, “it’s hard to be devout”, she says. But she holds onto Catholicism’s social benefits: “It provides ways for me and my family to be close.”

Marikit Santiago: Proclaim Your Death!

Campbelltown Arts Centre

Until 16 March