Art books are portable museums—or that’s how we like to talk about them. They can be inspiration or something to push back against. When Lindy Lee was a young artist, she found a Jan van Eyck book in the art school library and started photocopying. The grainy images got her thinking about the original and the copy, identity and value. The moment led to works like Untitled (After Jan van Eyck) (1985) and The Silence of Painters (1989), and a critical new chapter in her practice.

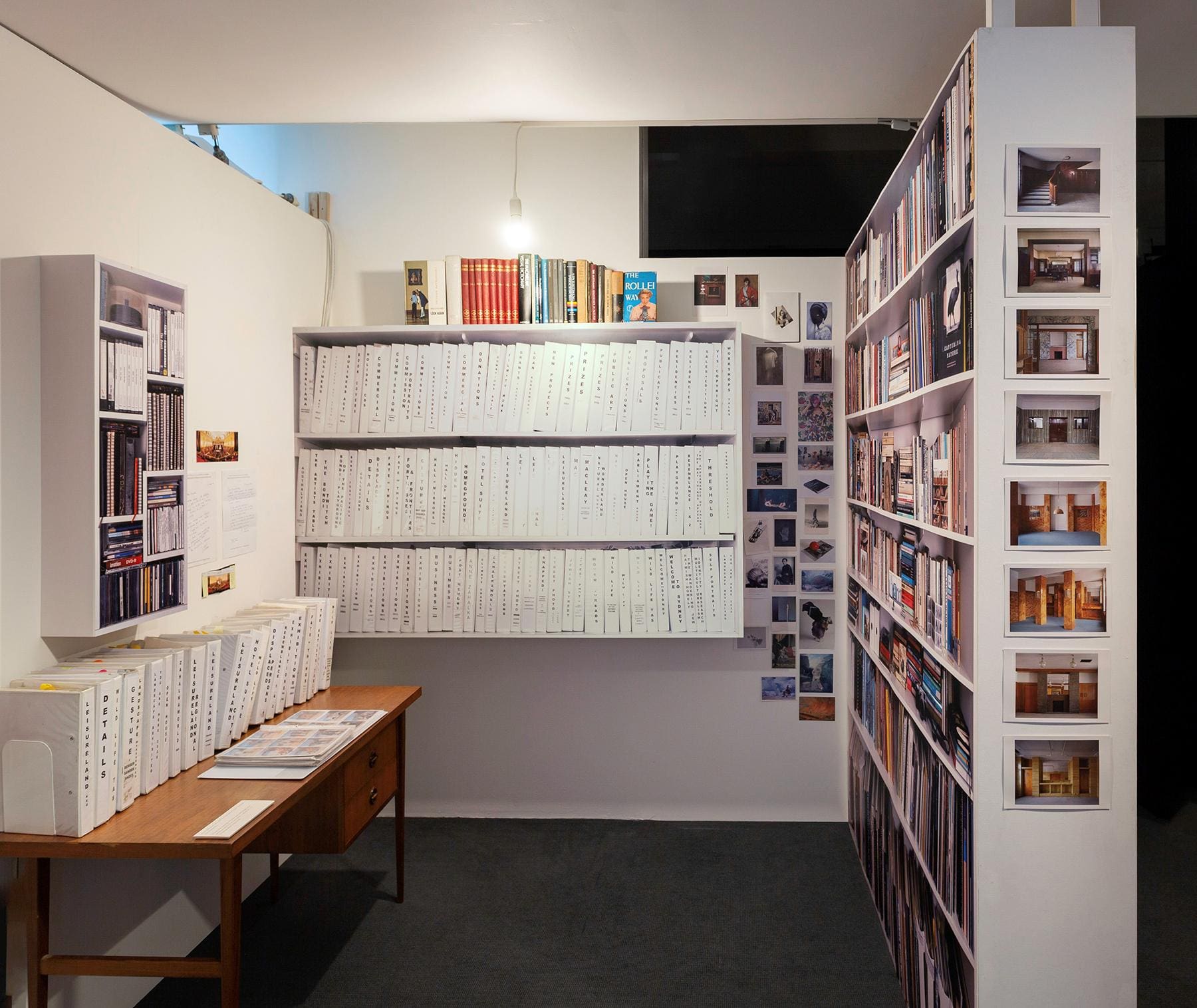

Books are present in Anne Zahalka’s practice too. For her Kunstkammer (2023), the photo artist made a life-size, trompe l’oeil recreation of her studio, complete with images of the neat binders on her shelves and a towering bookshelf. As an artist who works with historical compositions and methods of display, it was no surprise to see this proof of her research and curiosity, but the bookshelf in Kunstkammer felt surprisingly personal, like a mind laid bare. And that’s the thing. So many of us have stories about the books that have shaped us, from the chance discoveries to the treasured gifts from friends, and even the ones that got away. Books are research tools. They’re critical for artists, curators and audiences. But they’re often so much more.

Not to be coy. Monographs in particular have their role in the art market too. They’re markers of success. They record the breadth of an artist’s practice, and the critics, curators, galleries and institutions that have shown an interest. A good monograph has the power to set the narrative for decades. That means that while the emphasis is firmly on the cultural value, like so much in the art world, there’s often an exchange rate.

As one Australian arts publisher says on their website, “A book is a lasting legacy.” We take it for granted that books stay in circulation a long time, though arts publishing has its challenges. The market here is small. Data is patchy but print runs can range from 200 for an artist photo book to 1,000 to 2,000 for a major monograph, while themed or survey titles can target a wider art and design audience. In this tough landscape, it’s no small achievement to see titles like Atong Atem’s photobook Surat, co-published by Perimeter Editions and Photo Australia, reach a second printing.

“So many of us have stories about the books that have shaped us, from the chance discoveries to the treasured gifts from friends, and even the ones that got away. Books are research tools. They’re critical for artists, curators and audiences. But they’re often so much more.”

The recent emergence of new art libraries points to further obstacles. Australia already has several specialist libraries but as Melbourne Art Library’s founder Nell Fraser notes, they typically only exist within the state galleries and larger institutions. “It changes from library to library,” she says. “But some can be very difficult to get into unless you’re a student or a recognised researcher.”

The Melbourne Art Library was founded in 2020 to provide a more accessible option. It began as a doorstop-drop service and is now a lending library with a wide program of events, workshops and artists-in-residence. It’s growing quickly. The collection focuses on Australian art and history and includes magazines and ephemera like exhibition room sheets. There are already about 3,500 items, with more to be catalogued.

The new library has been welcomed by local artists. “Some are at university. Some have left university, or have never been to art school, but it’s a really wide range,” Fraser says. “We get a lot of people from design backgrounds too, so graphic designers and fashion designers, who love working with good quality art books as source material.”

One of Fraser’s guiding lights is Artexte in Montreal, a decades-old independent library with a substantial collection. “We want Melbourne Art Library to be a collection that has longevity,” Fraser says. “Setting up those formal structures so it exists in perpetuity, in the public realm, was really important.” It’s run as a not-for-profit and overseen by a board. But libraries are hardly money-making exercises and, as Fraser has discovered, they don’t easily fit existing grant programs either. Fraser hopes to continue building private support, and also to keep expanding the programming and collection. (Donations are welcome but please check with the library first.)

There are also growing networks in Sydney. The Art Gallery of New South Wales now has a vast public reading room and children’s library. The private Magenta House Redfern has added a 2000-strong library, open by appointment. 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art has also established a library onsite, cataloguing the thousands of books collected over the organisation’s 28-year-history. “A lot of the books in the collection are quite rare and unique,” says director Thea Baumann. “They’re not books that have received extensive distribution.”

For Baumann, the 4A library is about addressing a significant gap in public resources on contemporary Asian art and culture. While it’s still new, she sees it becoming a resource like the Asia Art Archive in Hong Kong. “We’re hoping for it to be a research hub for independent curators and a broader public that want to find out more about contemporary Asian art and culture,” she says. The new catalogue is searchable online. Like Fraser, Baumann says she is also thinking about programming and events, “so it’s not a library that’s gathering dust”.

Libraries are just one sign of the work going into getting books into readers’ hands. There are specialist bookstores, including Perimeter and independent distributor Books at Manic, along with events such as the Melbourne Art Book Fair and Same Page Art Book Fair. There are also a surprising number of publishers. There are the traditional publishers, like the international heavyweight Thames & Hudson and Australian firms Wakefield and New South, along with dedicated arts specialists like Art Ink, Perimeter Editions and Formist, as well as an extensive cast of institutions, commercial galleries and arts organisations.

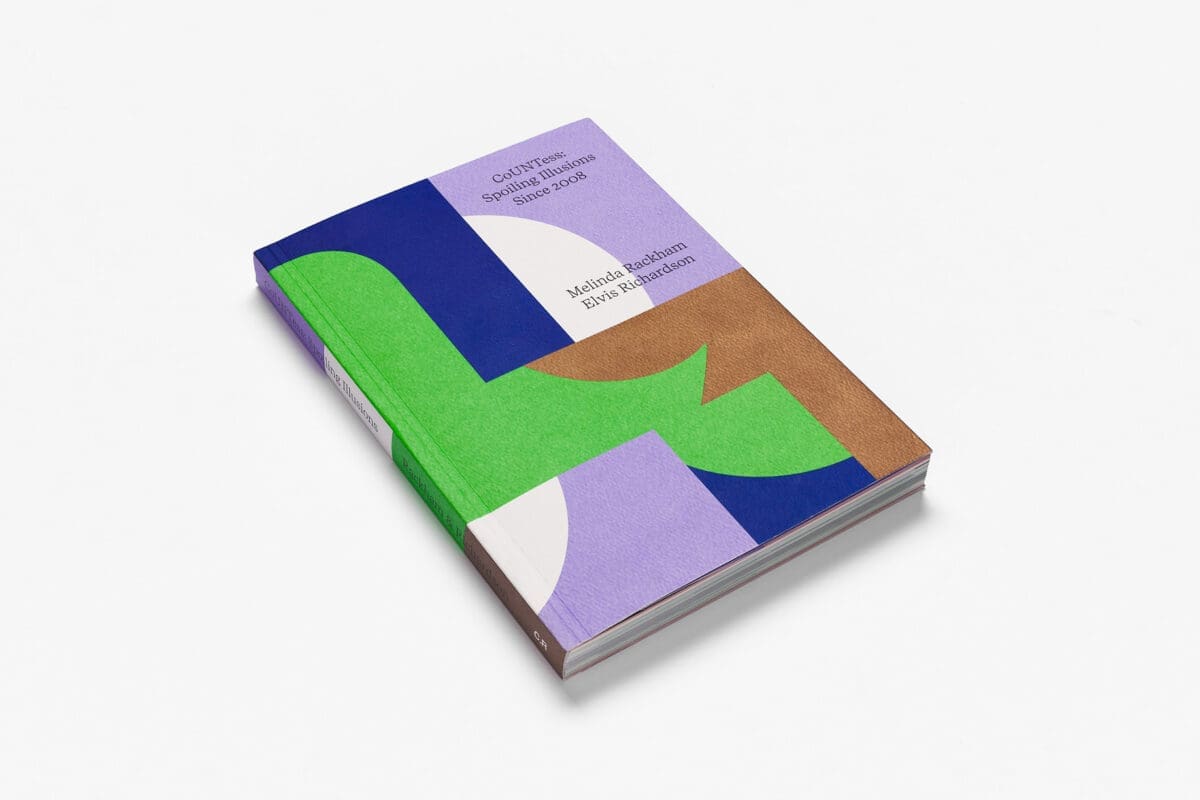

Many new publications are group efforts. The Countess Report, an independent artist-run research project, self-published CoUNTess: Spoiling Illusions Since 2008 with support from Creative Australia and Creative Victoria. Meanwhile, Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran’s monograph, Ramesh, was backed by Create NSW. It was published by Thames and Hudson Australia, which also published Vincent Namatjira’s self-titled monograph, which coincided with his solo exhibition at the Art Gallery of South Australia and the National Gallery of Australia. Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery worked with Formist to produce The First 40 Years, and the immense new monograph on Dale Frank was co-published by Neon Parc and Perimeter Editions. Of course, there’s a long history of institutions and galleries taking on the work of documenting exhibitions and artists’ practices. What’s curious is that the scope and creative ambition of these projects seems to be growing.

Different pressures and trends are at work here, but they’re guiding art books further into the sphere of collectable design objects. Some new monographs are now marketed as limited editions, like Sarah Contos’s Eye Lash Horizon. This language is not all that distant from artist books. Price is perhaps one reason. Large format, heavily illustrated titles are expensive to produce. At the upper end, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery: The First 40 Years is $110. The Dale Frank monograph is a cool $220. But arts audiences also place a high value on the experience. Dale Frank Artist, Artworks 2006–2023 is a hefty 37cm tall, signaling the grand scale of Frank’s works. Ramesh conjures a sense of the artist’s practice though bold colours and layouts, while Gemma Smith’s Found Ground from a few years ago had an inventive folding cover, setting out her playful approach to her practice. Art books are often creative statements in their own right.

At the same time, a wave of new art books is challenging dominant narratives, such as Variations: A More Diverse Picture of Contemporary Art, co-written by Tristen Harwood, Grace McQuilten and Anthony White and published by Monash University Publishing. Many of these new projects are guided by First Nations artists and thinkers and embody decolonial approaches, like the stunning monograph Madjem Bambandilla on the Wergaia and Wemba Wemba artist and activist Kelly Koumalatsos. This year also brings the publication of Brook Andrew’s marramarra on Indigenous artists working with history and healing, and the substantial exhibition catalogue 65,000 Years: A short history of Australian art, edited by Marcia Langton and Judith Ryan. Art books are records of changing cultural values, among their many other roles.

This article was originally published in the November/December print issue of Art Guide Australia.