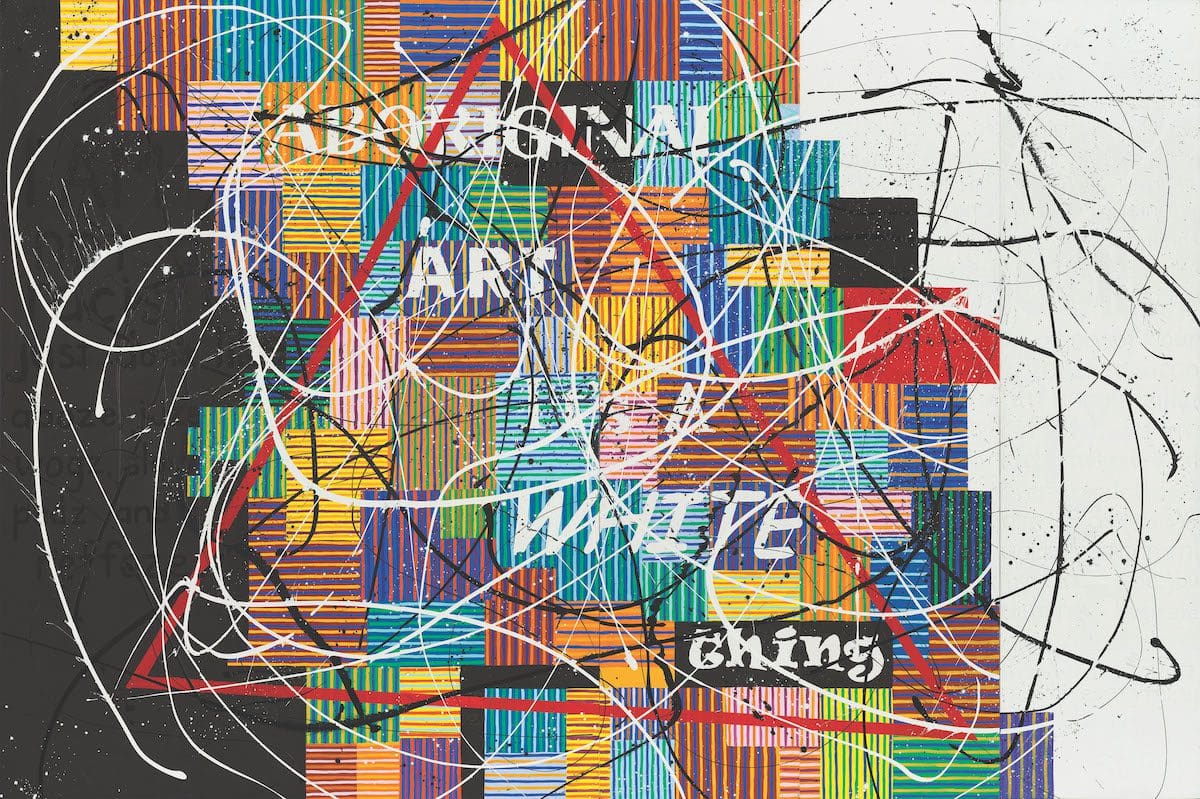

When Richard Bell swaggered to the stage at the opening of the 20th Telstra National Aboriginal andTorres Strait Islander Awards in 2003 to claim the first prize for his painting Scientia E Metaphysica (Bell’s Theorem), he wore the now infamous t-shirt emblazoned in large white lettering with “White girls can’t hump”.

Furore erupted, perhaps not so much in the crowd assembled on the front lawn of the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT), but certainly in the assembled media who sensed instantly(and with glee) that this incongruity of interpersonal truth, which was worn on the body of an Aboriginal artist and not framed within the confines of a gallery space, was not palatable in the world of the arts elite.

“The NATSIAAs have helped to shift, and indeed itself be shifted, in a further understanding of First Nations art practice as contemporary art practice—and this is significant and vital.”

The “Telstra Awards”, as the NATSIAAs are now colloquially known, have had their share of controversies and highlights, as have most other art awards around the country and globe, but perhaps less than some others. Being one of the oldest First Nations art awards in the country—established in 1984, and now featuring annual awards in a variety of artistic categories—has meant that it has become, in someways, the Elder of the First Nations art awards; to be respected and to be acknowledged as having done the preliminary work, long before other awards, of understanding its place in the First Nations and Australian contemporary art ecosystem, and the place of First Nations art awards nationally.

The NATSIAAs have helped to shift, and indeed itself be shifted, in a further understanding of First Nations art practice as contemporary art practice—and this is significant and vital.

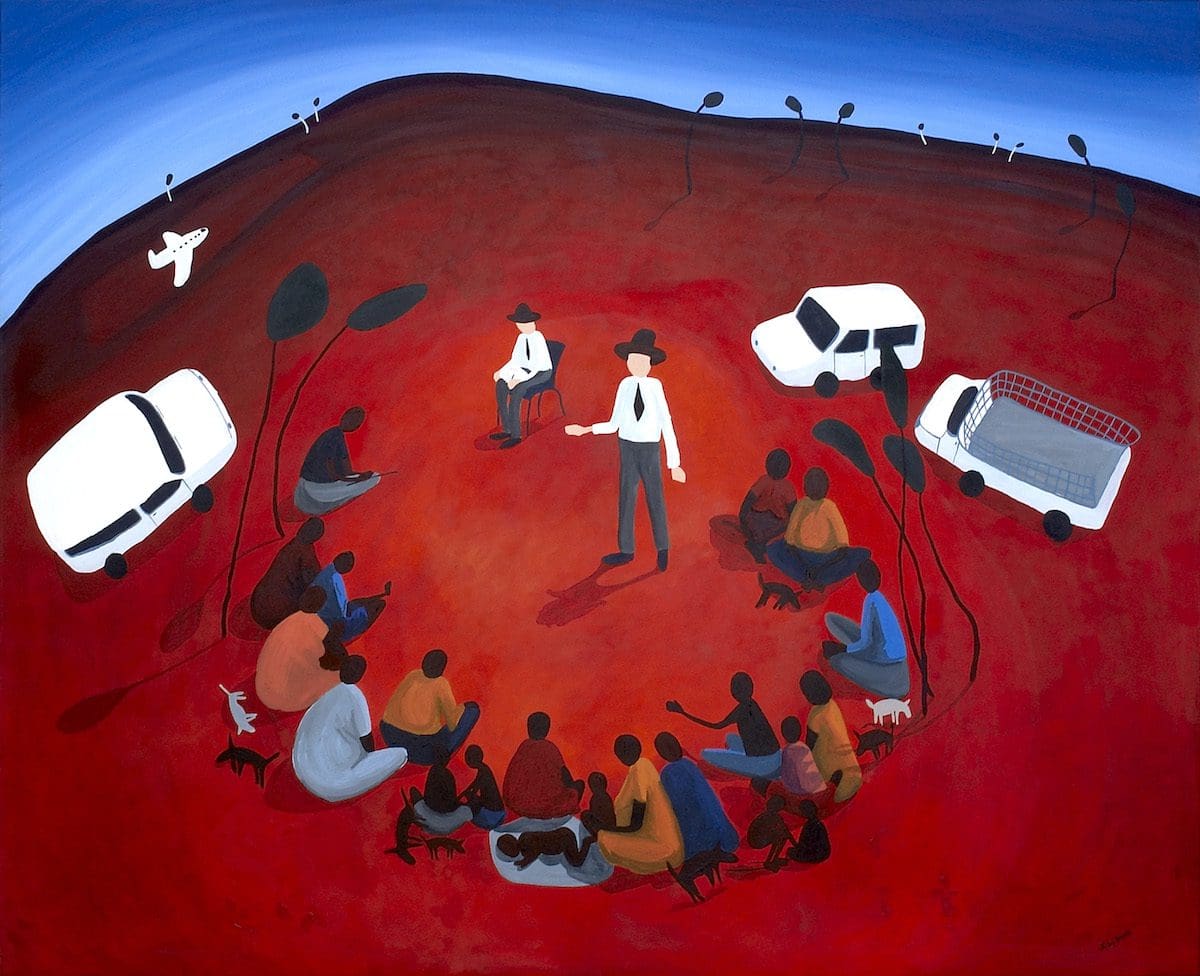

Art as political performance, such that it is, has taken place in the judging also. Tony Albert’s compelling work We Can Be Heroes was selected as the overall winner in 2014 by me, Tina Baum, curator at the National Gallery of Australia, and David Broker, former director of Canberra Contemporary Art Space. It was selected against the backdrop of the Black Lives Matter movement which had begun less than a year previously in the United States.

Albert’s work was an image of a young Aboriginal man with a bright red target on his chest, an agitate for the viewer to consider that young black men in this country at the time were targets of intense racial violence—and indeed still are. The discussions we had about the work winning were complicated, taking into account the challenge of the work itself for both artist and viewer—but ultimately it was selected for its ability to concisely summarise the Aboriginal experience of that moment.

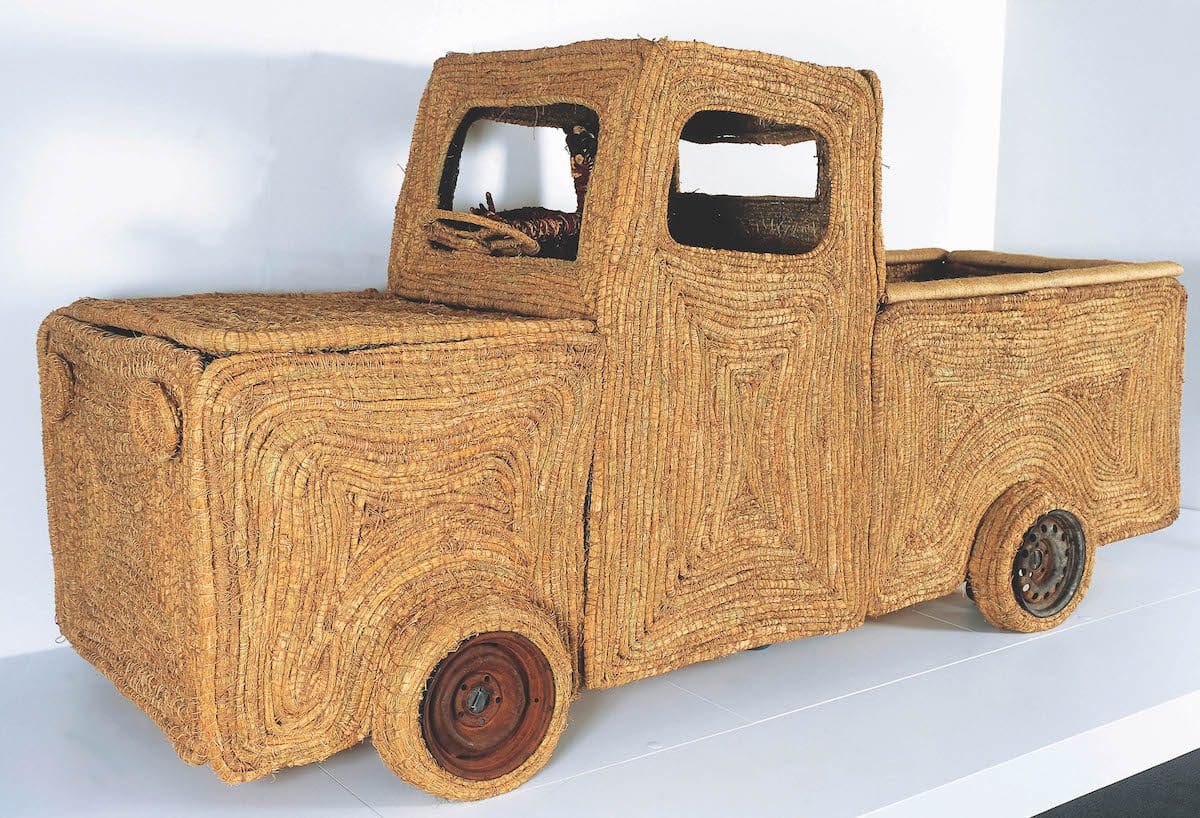

There are some moments that are memorable for other reasons. The delightful Tjanpi Grass Toyota, the winning entry in 2005 from the Blackstone Tjanpi Weavers, remains a crowd favourite when it is installed, for its life-size depiction of the ubiquitous ‘Troopie’ vehicle that transports artists and community members to remote locations for cultural business, art practices and hunting.

Far more than just a replication of a car, this work educates folk who have not spent time in remote communities about the necessity of travel, of transport through and around Country, and the lifeline this brings to cultural and intergenerational transmission of knowledge.

“Given that the Darwin Festival and the National Indigenous Music Awards also open at roughly the same time as the NATSIAAs, the event attracts enormous crowds from the arts ecosystem and the public alike. “

The NATSIAAs have led the country in recognising the work of bark painters as contemporary practitioners, and represented them as such in a broader contemporary context. This has meant not only showcasing some of the greatest bark and lorrkon painters of our time, such as John Mawurndjul, Ms D Yunupingu and Djambawa Marawili, but presenting them in such a way that the public have understood the cultural material of these and other artists to be contemporary arts practice, transmit-ting cultural knowledges and embodying political documents of sovereignty simultaneously.

The NATSIAAs have long been contextualised by the community in which it is represented. The Larrakia people of Darwin have graciously allowed its hosting on Larrakia Country, but it is unique in that First Nations communities from literally every corner of the nation assemble in place to participate in the opening weekend celebrations.

Given that the Darwin Festival and the National Indigenous Music Awards also open at roughly the same time as the NATSIAAs, the event attracts enormous crowds from the arts ecosystem and the public alike. When the award first began, it was slow to attract entries from the eastern and southern parts of the continent, but with much labour over many years by the founder of the award, Margie West, and subsequent curator Luke Scholes, it has changed in response to the way First Nations communities have positioned their practices.

MAGNT now has a First Nations curator at the helm of the NATSIAAs, Arabana, Kala Lagaw Ya and Wuthathi woman Rebekah Raymond, who is part of the next generation of First Nations curators who will transform the art awards yet again, in step with the prevailing practices and desires of First Nations artists and communities themselves. We look fondly back at the last 40 years of NATSIAA and eagerly forward to the next.

40: Celebrating four decades of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards

Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory

(Darwin NT)

On now—29 October