Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

Every two years the JamFactory’s satellite gallery at Seppeltsfield presents an exhibition centred on Barossa Valley heritage. This year, JamFactory curator Caitlin Eyre has explored the region’s long-standing connection to Germany in Kinder, Küche, Kirche: Revisiting the Traditions of Barossan Women’s Folk Crafts. Part of the South Australian Living Artist Festival, the exhibition links historical pieces with the work of ten contemporary female artists to trace the development of German craft traditions in the Barossa and how these practices have contributed to the resilience of relationships forged between women in times of hardship.

Reinterpreting the home-based crafts associated with these domestic spheres as powerful objects connecting families across generations, Eyre sees handmade crafts as a way to rebuild cultural identity and establish a sense of kinship when far from home.

“There is a utilitarian factor to being able to provide for your family in terms of clothing and having nice things around the home,” says Eyre. “But I also think women’s crafts have been a way to show love for family, recognise friendships and ties to community – whether it be making something for church, a friend or to commemorate the birth of a baby – handmade objects from someone we love have always had a special place in our lives.”

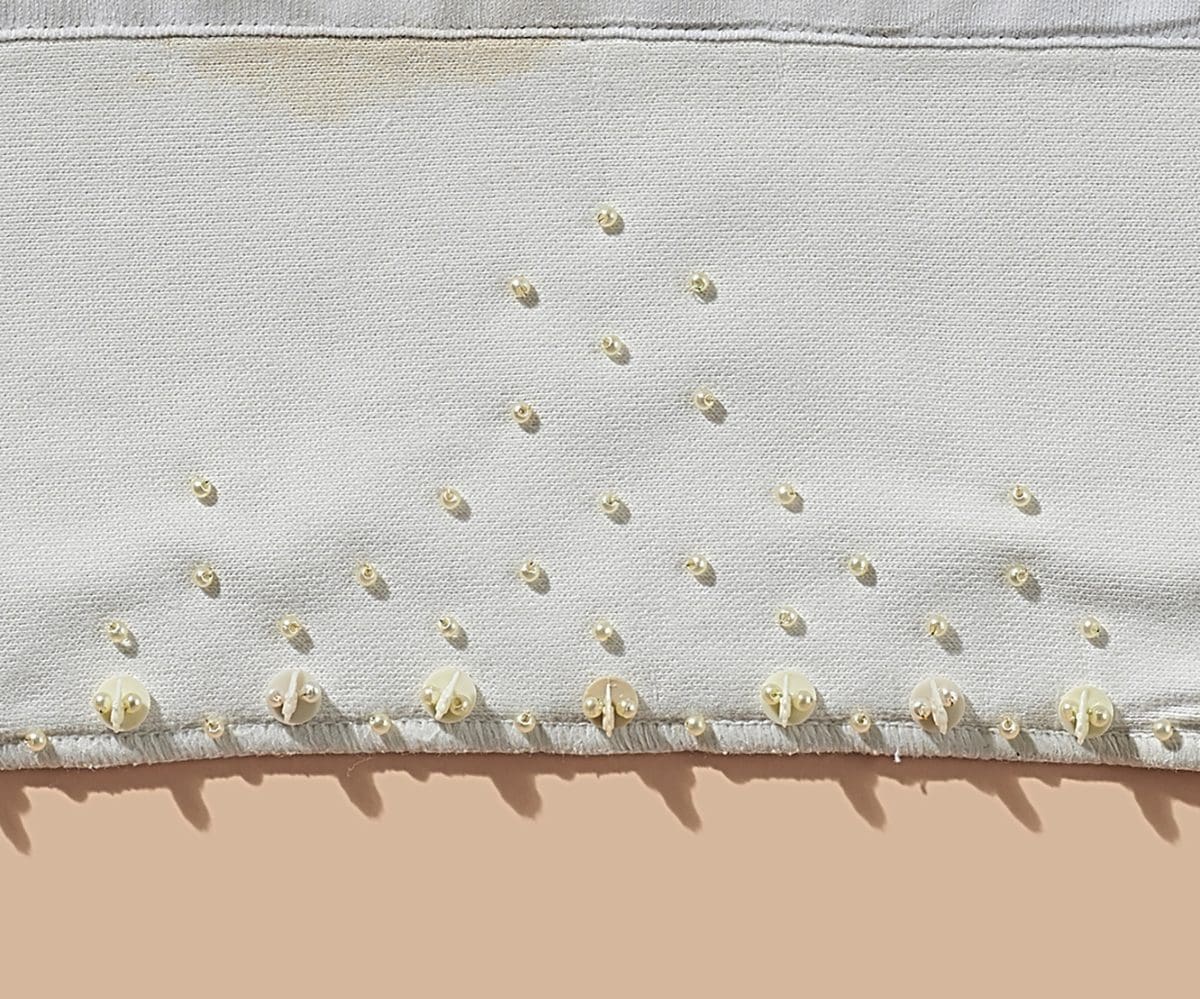

In addition to the historical examples of handmade clothing, intricate red and white embroidery, lacework, doilies and corsages from private collections, the contemporary works respond to the values and techniques evident in the older pieces. For Kinder, Küche, Kirche, Rose-Anne Russell, a leather worker based in the Barossa, deviates from her regular shoemaking practice to create a series of native flowers finely crafted from leather and placed beneath glass domes like exotic plant specimens. “A very Victorian-era pursuit was putting botanicals – either real or crafted – in frames or under glass,” Eyre says. “Russell’s leather flowers play on the idea of eternal flowers; immortal flowers that last forever.”

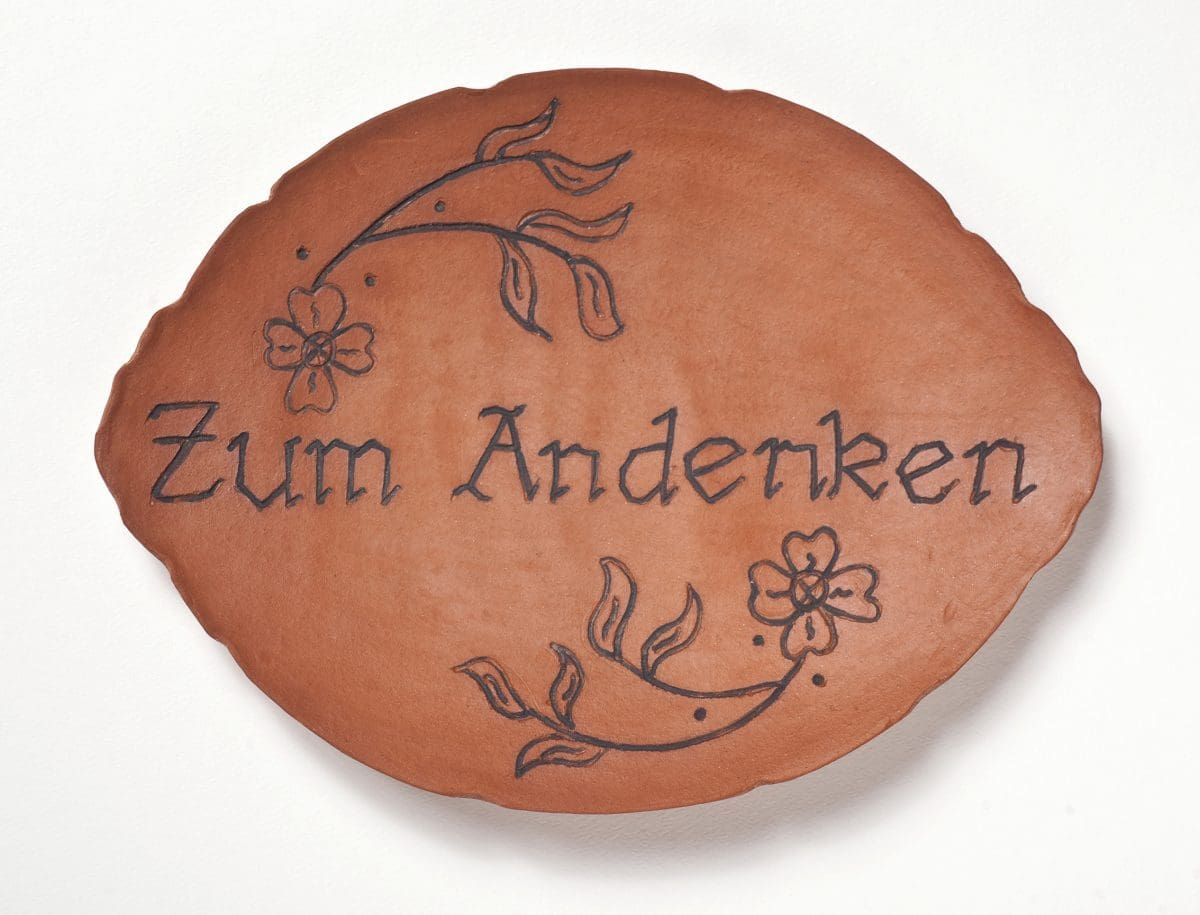

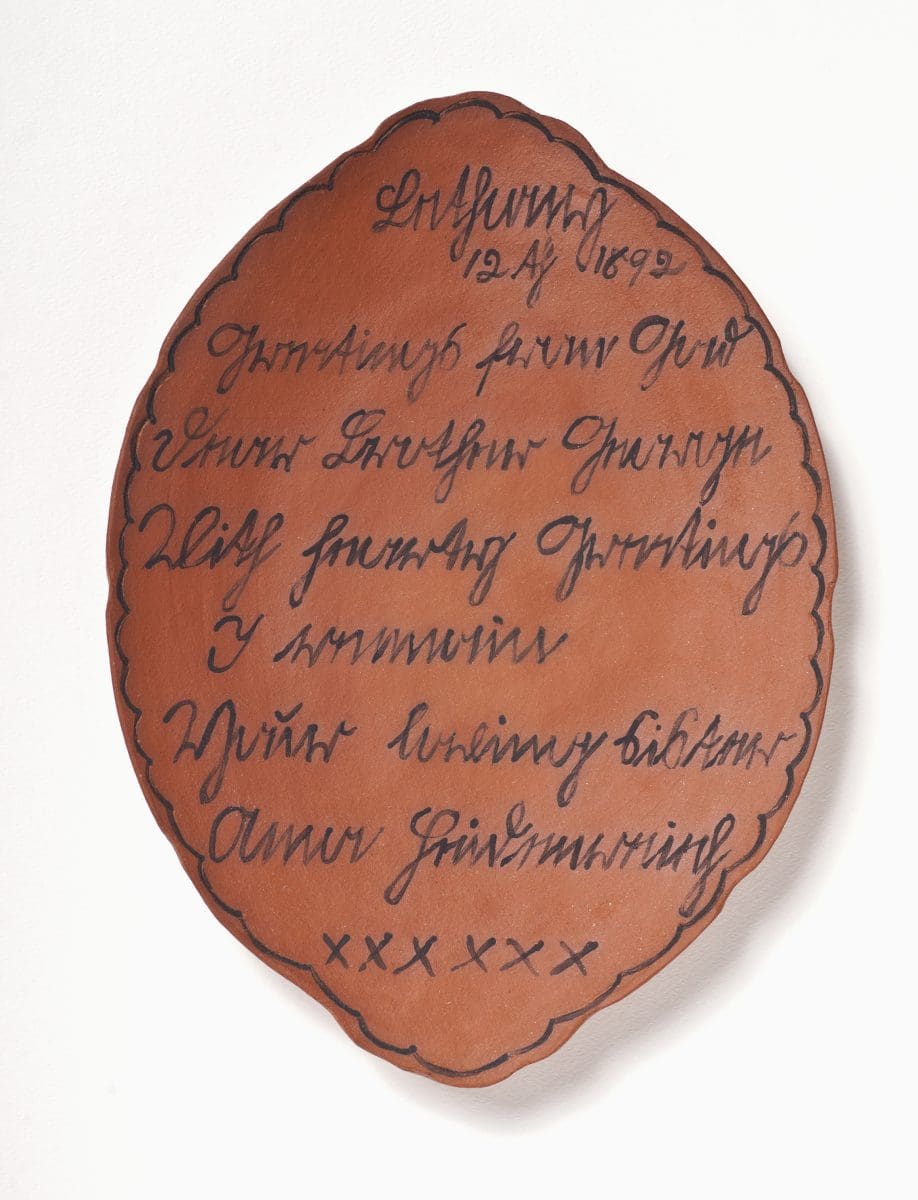

Exploring her German Lutheran heritage and her familial connection to Hermannsburg missionaries, artist Kylie Waters has used the moulds of ceramics passed down through her family to produce a series of souvenir plates commemorating personal memories.

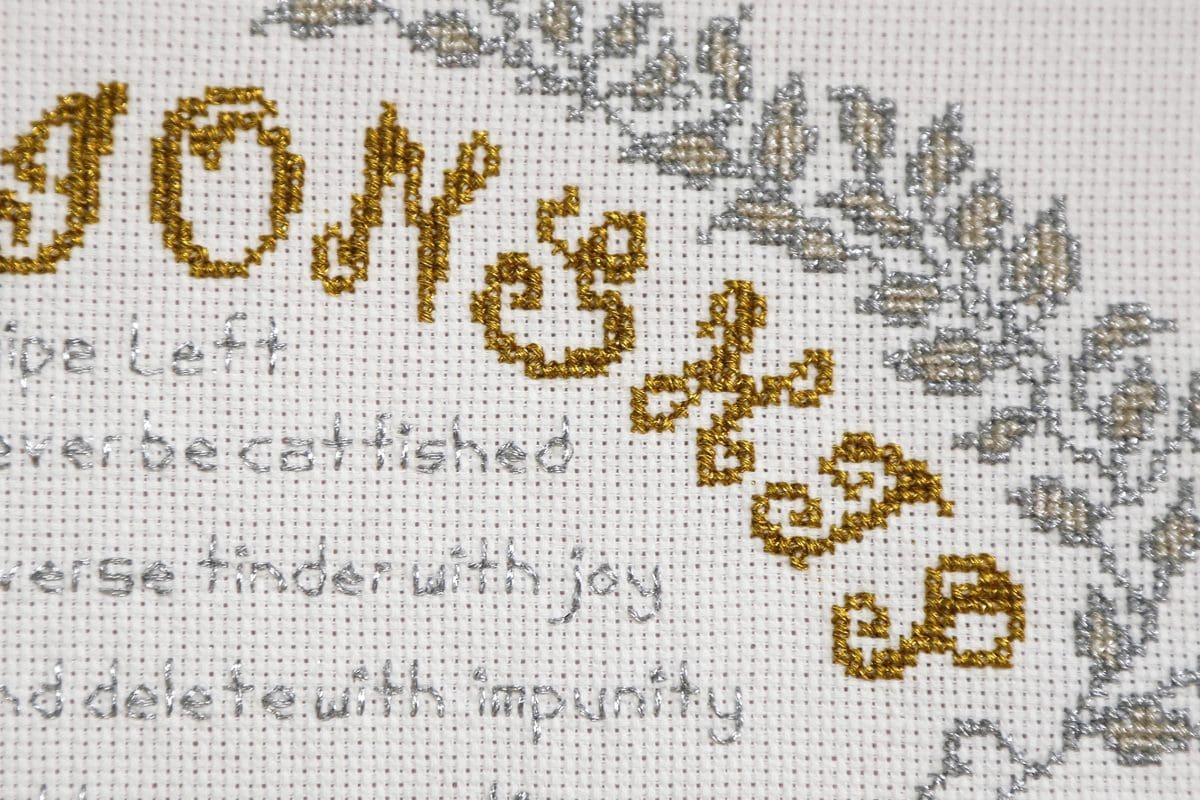

Linking the past to the present, emerging textile artist Makeda Duong employs traditional embroidery techniques to stitch a relationship status – similar to those publicly announced on Tinder and Facebook – in the highly decorative style of an embroidered wedding certificate. “A big thing for the German Lutherans was making framed certificates and decorative memorial tokens of marriages,” explains Eyre. “For every significant wedding anniversary, they would make a special embroidered picture which would include embroidered text, usually with a religious tone.”

Also including the work of Deborah Prior, Rita Koehler, Brigitta Keane, Brigitte Jeanson, Diane Hedger, Ursula Halpin, Joy Day and Ilona Glastonbury, Kinder, Küche, Kirche evocatively demonstrates the enduring importance of the handmade object in the Barossa community. “While the definitions of women’s expected roles in society have certainly changed, many women still show their love for friends and family through the act of making,” says Eyre. “In this exhibition, the contemporary artists reinforce this idea in a way that reclaims craft as an intensely significant and symbolic practice.”

Kinder, Küche, Kirche: Revisiting the Traditions of Barossan Women’s Folk Crafts

JamFactory: Seppeltsfield

13 July – 15 September