Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

Indian artist Tanya Goel spent her formative years in some of the world’s great metropolises. Born and raised in Delhi, she undertook post-graduate study in the USA: initially in Chicago (home of the first skyscraper) and then an MFA at Yale. After a year in New York, perhaps still the most iconic Western city worldwide, she returned to Delhi, a massive metropolis both ancient and swiftly changing. So it comes as no real surprise to find that the embodied experience of contemporary urban life is at the heart of her fractured grid paintings. “I want the eye to rest on nothing” Goel says, “similar to the fragmented experience of living in post-industrial, digital cities.”

According to the most recent United Nations report on global urbanisation, 54.5 percent of the global human population now lives in metropolitan centres. The pace of urbanisation is frenetic and its effects are immense. As a participating artist in the 2018 Biennale of Sydney, Goel can see for herself its impact on this rapidly expanding city. But urbanisation is particularly fast-paced in countries like India. Delhi is the second largest city in the world, and while the population of the first (Tokyo) is in decline, the population of Delhi is still swelling and is estimated to reach some 35 million by 2030.

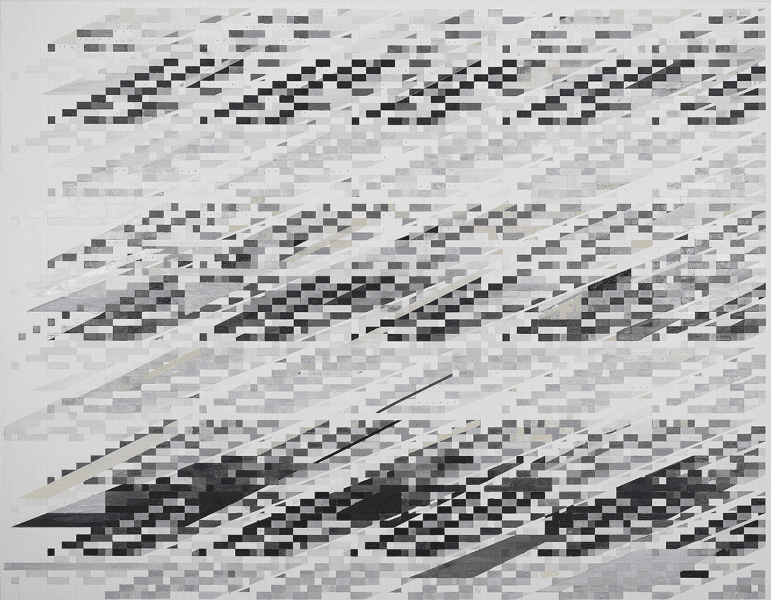

The grids that anchor Goel’s paintings are an overt (if abstract) reference to the geography of a city. As she points out, “Every city is planned around a grid of sorts, whether it be Cartesian, circular or diagonal.” But Goel’s compositions also conjure up the inherent architecture of digital images, especially that frozen moment when they start to corrupt and rupture into individual pixels. And this is no coincidence, as an artist Goel is interested in the city as a layered temporal experience; a complex, multivalent interface that, in the post-digital age, inevitably includes the screen.

For Goel, the screen is something of a paradox. One of its key characteristics is that it obliterates old images to create new ones, a process which the artist also sees taking place in real-time in her hometown. “There has been rapid development and expansion of the built environment/grid in Delhi, due to the complete lack of restrictions on construction,” she explains. “The only constant is the sound of structures being broken to the ground only to be rebuilt, and all things familiar are being demolished, far too quickly.”

Goel has responded to this destruction by creating her own pigments from the crushed remains of modernist homes from the 1950s and 1960s, the comfortable urban backdrop of her childhood. In this way, her fragmented grids are literally memorials to what is being lost. But, as their internal order disintegrates into chaos, they are also a meditation on the unstable dynamics of memory.

The artist’s interest in the temporality of both the screen and memory come together in her use of weaving as a metaphor. At first the link may seem tenuous, but as she points out, both digital and weaving technologies utilise an x and y axis, and the punch-cards used in the innovative 19th century Jacquard loom were an early form of memory processing that went on to influence the development of modern computer coding.

Goel’s interest in what she calls “moments that start to rupture the grid” comes back to her lived urban experience in Delhi, a city in a constant state of flux.

Seemingly unfettered urban development is something Delhi shares with Sydney, and the artist’s paintings are bound to resonate with visitors to Artspace during the Biennale of Sydney. As she says, “The paintings are abstract records that document vanishing landscapes and chronicle the emergence of new urban centres” – something Sydney-siders are all too familiar with.

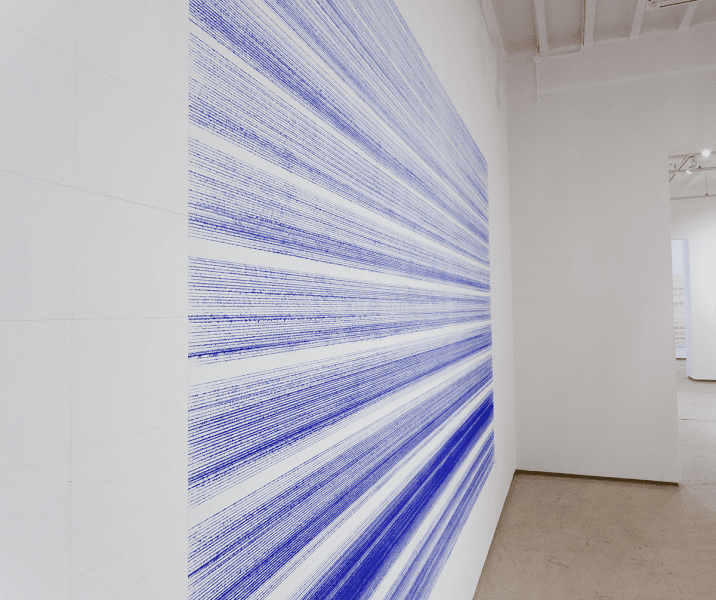

At the Biennale, Goel presents a series of frescoes made using found debris from modernist buildings; two series of paintings from 2017, Carbon (extension lines) and Carbon (frequencies on x, y axis), which both use pigments handmade from coal, aluminium, concrete and mica; and a site-specific wall drawing, Index: pages (builders drawing), 2018.

Infused with urban life, Tanya Goel’s works reference both weaving and the screen, mathematics and memory. Her handmade pigments are a kind of experimental chemistry, her grids an emotive cartography of loss. Her paintings are a potent mix of art and science. As she says, “perhaps that is the most profound thing about art; its ability to be anything, nothing, and everything.”

Tanya Goel

21st Biennale of Sydney

Artspace

16 March – 11 June