Material curiosities: Primavera 2025

In its 34th year, Primavera—the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s annual survey of Australian artists 35 and under—might be about to age out of itself, but with age it seems, comes wisdom and perspective.

Khaled Sabsabi migrated to Australia with his family in the early years of the protracted and bloody Lebanese civil war (1975-1990). Settling in Western Sydney, where he is still based, he has worked with local communities extensively since the 1980s developing art-based programs aimed at vocalising and investigating migrant experiences.

Sabsabi found a home in hip-hop, in what was then a promising culture of resistance and identity. In 1988 when Ice Cube rapped, “I’m brown/ and not the other colour/ so police think/ they have the authority/ to kill a minority” – he could have been rousing a Palestinian or a person of colour in Trump’s America.

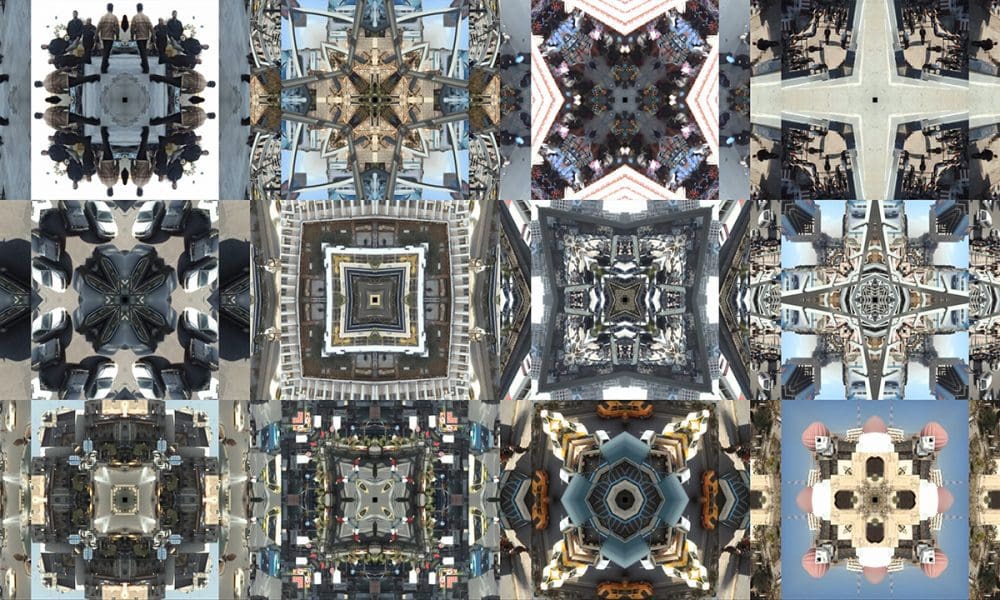

Sabsabi’s works now take the form of video-based installations, sound art and photography. He has exhibited widely in Australia and internationally since stepping into visual arts in the late 1990s.

Varia Karipoff—You were born in Tripoli, Lebanon. What do you remember most vividly from your childhood?

Khaled Sabsabi—My strongest childhood memory would be the look on my grandmother’s face when we left her behind in Tripoli to flee the civil war.

VK—At the age of 12, your family migrated to Australia. What were your thoughts about the move back then?

KS—I thought of it as a travel to another place, a safe place, also as an intermediate wait for the civil unrest to subside back home. Of course this didn’t happen, and the civil war went on for near two decades.

VK—How has that idea of Australia as an intermediate place shifted for you?

KS—I do regard Australia as my primary and physical home; I do have reservations about its history and social behaviours, but so do millions of other Australians. In regard to Lebanon and the surrounding region, to be frank, it is a love/hate relationship. I can’t wait to go back and as soon as I’m back I can’t wait to leave. I think it’s because I’ve become accustomed to the complacent outlook here, or it may be a form of post-traumatic stress, I am not sure.

VK—You returned to Lebanon for the first time in 2002. How do you find the difference in energy and pace between your country of birth and Australia? Have you reconciled the differences?

KS—Since 2002 I’ve been back and forth between Australia and the Middle East many times. And during these 15 years I’ve witnessed many changes in both places on multiple levels, which I don’t care to list. I’m still trying to work out what this cultural and emotional duality means.

VK—Tell me about your hip-hop performance days. What drew you to hip-hop culture? Was there a strong community?

KS—What drew me to hip-hop subculture in the mid to late 80s was a personal belief that hip-hop was a genuine platform and a unified demonstration for the alterative and so-called minor voice to speak and be heard. It was also an opportunity for a new social being to exist for our communities, outside the mainstream – one that was not driven by capitalist political ideologies and government-driven organisations of that time.

As naive as it may sound, this is how many of us saw the hip-hop subculture globally. But unfortunately capitalism found ways to commodify and appropriate the subculture, twisting and eventually killing it as well.

VK—From hip-hop, how did you find your way to the visual arts?

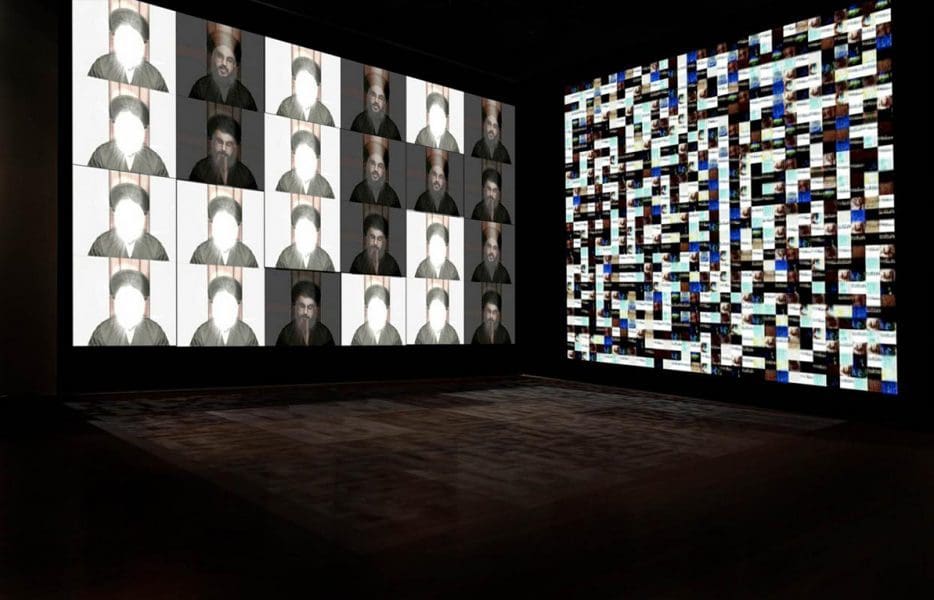

KS—My first attempt to present what we define as visual art was in 1998, producing a mixed-media site-specific installation. The moment art really captured my imagination about its possibilities was in 2001 when I produced a simple work titled Where we at. I had 12 white t-shirts printed with the face of Osama bin Laden in black and white with ‘Made in Australia’ collar tags. This work was made pre 9/11 and I did it to intentionally see how my community, and the broader public, would engage and respond to the idea of local radicalisation and what is to come.

VK—Art and activism are very much linked in your work, how do you see the two fitting together?

KS—Yes in my case, art and activism are one; they are indivisible.

VK—Your works often bring to attention some facet of spirituality, in particular Islam and Sufism.

KS—This is a personal interest, one that is about finding a way to communicate inclusivity and acceptance. Sufism, I believe, allows the individual to be both the thinker and feeler and to be inspired by notions of compassion and actions of the heart.

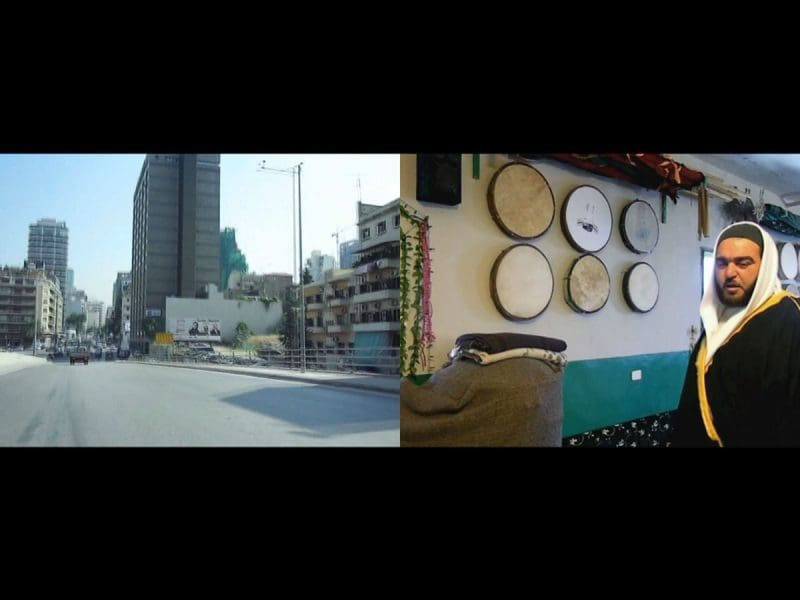

VK—In Bring the Silence, (five-channel AV installation) viewers will have a rare insight into Sufi shrine traditions and customs. What is your intention in placing such a ceremony into a public space like Cockatoo Island at the Biennale of Sydney. Is there an attempt to demystify and punch a hole in our outlook of Islam?

KS—The work Bring the Silence offers multiple perspectives for the viewer detailing the way Sufism deals with ideas surrounding contentment and acceptance as well as ideas relating to the seen and unseen realms – what we witness and what we feel. For context; the work’s central point is a Maqām (in Arabic) of Muhammad Nizamuddin Auliya (1238 – 1325 CE). Maqām are sacred burial sites of Sufi saints that are associated with spirituality and enlightenment. For thousands of years these spaces held and continue to hold much personal meaning for many people and cultures. I value and respect these traditions and genuinely consider them as invitations to seek hope in a most critical time, where our progression, evolvement and existence as a species further perpetuates and affirms an unsustainable spiral and path.

VK—Your practice has detailed multiple angles of the Islamic experience including a personal rumination on both global issues like war and terrorism. With works like At the speed of light at ACE Open, Guerrilla at Adelaide Biennial and Bring the silence, is there now a shift to intimate cultural and spiritual insights?

KS—Like many others, I regard Sufism as the inner and mystical spiritual dimension of many faiths, a practice that fosters cultural acceptance and respect. And in a climate of global turmoil, with the intention of erasing history to control the new future, I find Sufism like art, is at the crossroads of the spiritual and the profane, in which both conditions exist and coexist.

VK—What is your primary way of interacting with the world – for instance, emotionally, intellectually, socially, or through physical senses?

KS—Good question, I think through art, wholly at this time and place. I’m still passionate, inspired and committed to making work that speaks in ways that may enlighten our understanding of who we are. For the future; I love and find strength in Saint Charbel’s (18th century Maronite Christian) last words to the people of his village before choosing to remain silent for 19 years; ‘if you don’t under- stand my silence then how can you understand my words’, wonderful.

VK—Can you describe the way you work?

KS—My practice involves working across art mediums, geographical borders and cultures to create immersive and engaging art experiences. The mindset behind my work process is to generate opportunities for social growth, progress and rethinking through the arts.

Let’s be clear though; what I am exploring and presenting isn’t new. In addition, the mediums and the way I work aren’t new either. The only point of difference is what informs my work; the person that I am, my experiences, thoughts and memories.

VK—What is the most important lesson you have learned, so far?

KS—Patience is key and once I’m out of patience I will stop making art.

VK—What are you reading at the moment?

KS—I am revisiting The Prophet by Khalil Gibran; it’s a great work.

Waqt al-tagheer: Time of change

ACE Open

3 March – 21 April

Bring the silence

21st Biennale of Sydney

Cockatoo Island

16 March – 11 June