How slipshod could so-called enlightened Europeans documenting Indigenous language and culture be? Their mistakes and mistranslations – and the resultant loss of knowledge – were on the mind of artist James Tylor when he began a photographic series on Kaurna country, across the Adelaide plains, in 2012.

Tylor is one of four artists headlining this year’s Adelaide // International. Of Nunga (Kaurna), Maori (Te Arawa) and European ancestry, the artist has fastidiously arranged 18 of his landscape images geographically across one large wall at the Samstag Museum of Art, ranging from the Barossa Valley to Kangaroo Island, as the latest iteration of his ongoing series From an Untouched Landscape.

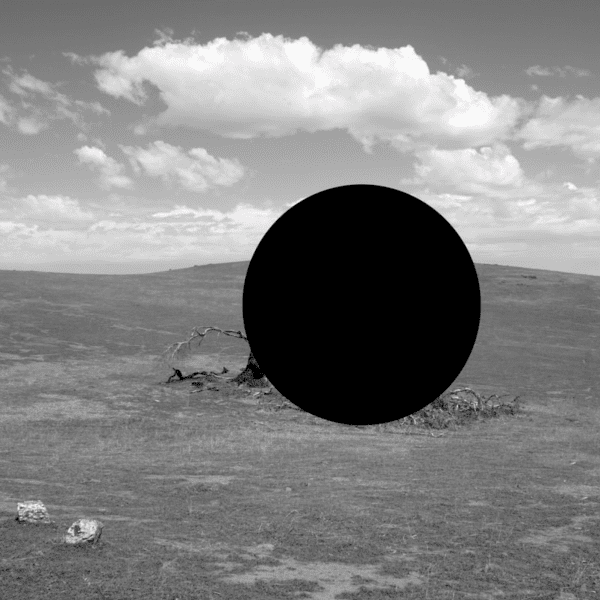

Large round holes cut in the photographs show a velvet backing, a reference to the black velvet used in a photography process known as ambrotype, popular in Australia in the 19th century. But this velvet void or cushion of “absolute black shadow” also symbolises gaps in the historical record, due to the chaos of colonialism and conflict.

“It’s about absence, and pretty much any idea about removal,” says Tylor of the velvet holes, pushing his baby son in a pram at Adelaide’s Samstag Museum of Art during this Art Guide interview about the photographs (combined here with a sound installation under the title The Darkness of Enlightenment).

The photographs are carefully interspersed with 30 Kaurna objects Tylor has made, mostly in painted wood. The object designs, which also include stone, change significantly as the display is read from left to right, or north to south.

“People were just forced to leave and then onto missions. Then the mission people weren’t allowed to practice culture or language, so it led to a massive deficit in cultural knowledge.”

Tylor has collaborated here with Melbourne-based Koori sound artist Anna Liebzeit, whose recordings include conversations with Kaurna elders in Kaurna language as well as deliberately dark and distorted music, mostly percussion, by the artist and Jack Buckskin, combining in a dynamic installation.

Preparing these works, Tylor has invested a lot of time studying colonists’ journals and then having them interpreted by Kaurna community members. Born and growing up in Mildura, Victoria, where his parents met, he visited Kaurna country regularly. As a child, he learned to carve, and applied skills from a carpentry apprenticeship to reproducing the 19th century Kaurna artefacts he has seen in museums and in drawings.

Tylor is also among Indigenous activists campaigning for the return of 14 Indigenous objects – including shields, spears, clubs and boomerangs – from museums in Dresden and Leipzig in Germany; many of the missionaries to South Australia were German Lutherans.

These Lutherans, whose first language was of course German, were commissioned by museums to create a Kaurna dictionary translated into English. “The missionaries wanted to convert [Indigenous] people to Christianity, but they really struggled,” says Tylor. He notes that they contributed to what became known as the stolen generations. “Kaurna [children] were taken 700 kilometres around the coast to Port Lincoln and onto Poonindie mission, to remove them from their parents, so that the missionaries could teach English only, without any distraction.”

Curator Gillian Brown says in creating Kaurna objects Tylor has assisted museums and collecting institutions who are “interested in redressing the ethics of their collections”.

“Many of the objects in our public institutions were perhaps not collected ethically, nor was correct documentation and consultation undertaken. He’s an artist who does an incredible amount of research, and I’ve been thinking about his exhibition as advocating for nuance in collections and museums and understanding.”

This year’s Adelaide // International “views the future as an unmade shared space,” says Brown. The emphasis is “on building a future with present-day actions” via “the communal, the potential, the alternative.”She speaks of the art helping us view the world through a “reparative lens.”

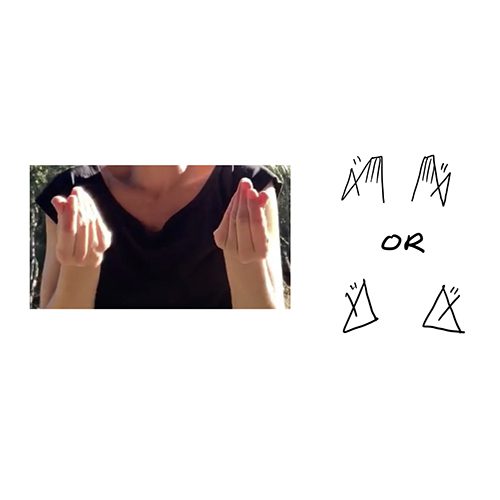

Fayen d’Evie’s Endnote: The Ethical Handling of Empty Spaces, considers a language for post human audiences – which in the installation looks like a hybrid of hieroglyphics and emojis.

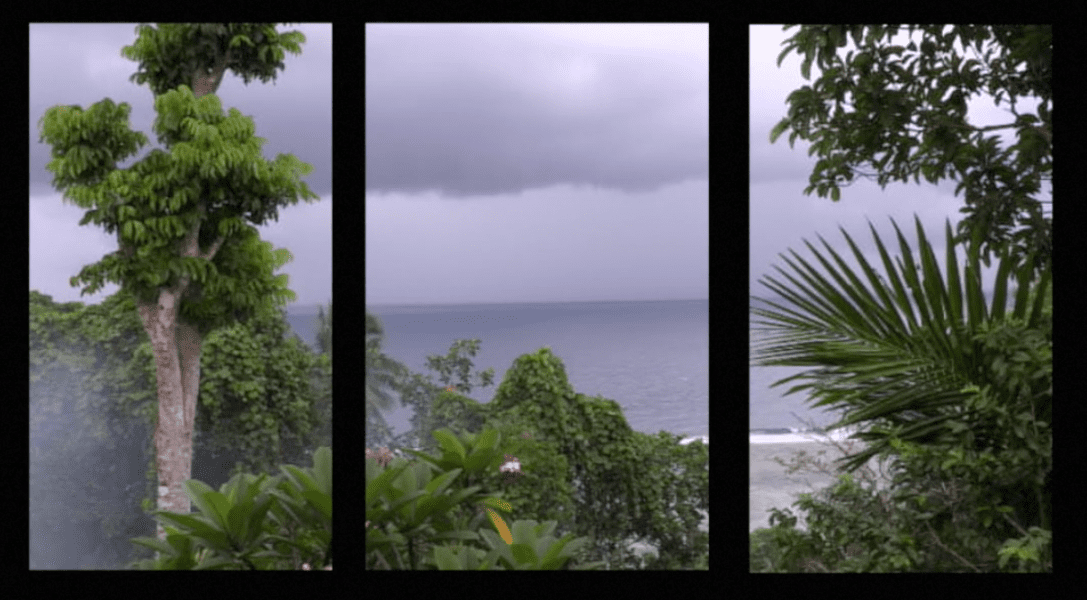

Meanwhile Taloi Havini’s video work Tsomi Wan-Bel focuses on systems of justice through a traditional meditation ceremony in Northern Bougainville, the Autonomous Region of Bougainville.

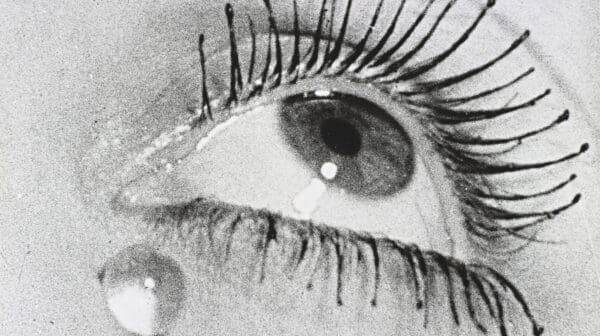

Irish artist Jesse Jones’ Tremble, Tremble, the first iteration of which was created for the 2017 Venice Biennale, fills up a large darkened ground floor gallery with giant video screens showing the enigmatic Irish performer Owen Fouéré, recently in Australia to perform in the Sydney Festival show The Last Season.

Here, Fouéré plays a mythological witch-like figure, reading the artist’s fictional law that proclaims a new social order created from a female perspective. The title of the work is derived from a slogan chanted at Italian feminist marches in the 1970s, but the timing here is perfect, coming just after South Australia became the last Australian state to decriminalise abortion.

“The works themselves, because some of them are older works, it’s an interesting example of how our reading of a work changes,” says Brown.

“Jesse’s is a really great example: not only have we gone through a global pandemic, but Jesse created this work in 2017, which was when the Eighth Amendment [of the Constitution of Ireland] was under debate. It was reversed in 2018, giving women back bodily autonomy. A similar thing has just happened in Adelaide a couple of weeks ago.”

Might audiences be reading through our present knowledge of pandemic and populist politics and the ensuing chaos?

“I’d certainly say so,” says Brown. “The exhibition’s focus on the future is a long-standing theme. But last year had such an impact on the way we experience the world and everything in it, so it was impossible for that not to filter through everything.”

Adelaide // International

Samstag Museum of Art

26 February – 1 April