The 10th National Indigenous Art Awards were announced on 27 May to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the 1967 referendum and the 25th anniversary of the landmark Mabo decision.

The National Indigenous Arts Awards recognise the artistic excellence and cultural leadership of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists.

The 2017 winners are:

Red Ochre Award for lifetime achievement: Dr Ken Thaiday Snr and Lynette Narkle

Dreaming Award for young artists: Teila Watson

Fellowship: Lisa Maza

Faith, dance, and truth: the art of 2017 Red Ochre award-winner Ken Thaiday Snr

By Leah Lui-Chivizhe

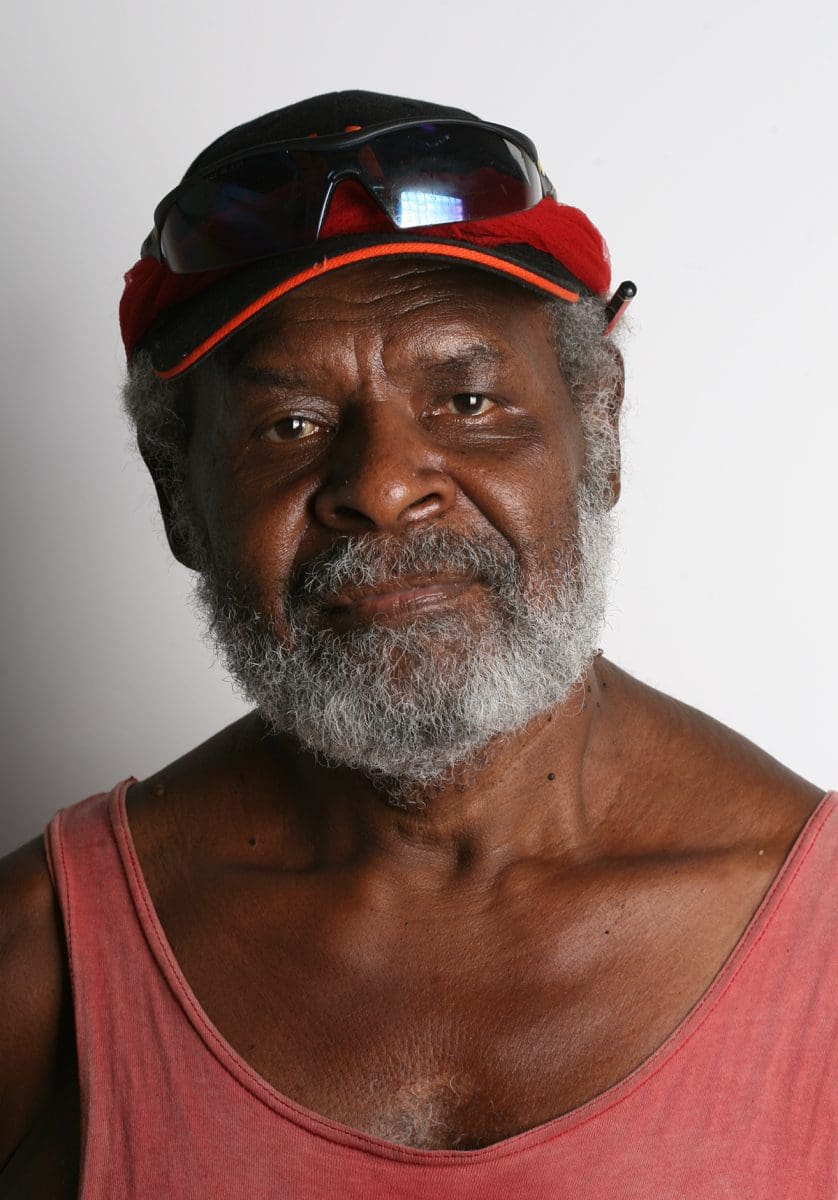

Over the last three decades, the ingenious sculptural telling of stories from the island of Erub has propelled Ken Thaiday Snr from being a maker of Torres Strait dance objects to an internationally acclaimed artist. Today his work has been recognised as a winner of the 2017 Red Ochre Award for his visual and performance art, alongside Lynette Narkle for her work in theatre, film and TV, as part of the Australia Council’s National Indigenous Art Awards.

Ken Thaiday is perhaps most famous for his elaborate dance masks and headdresses. In late 2014, I spent considerable time with him as he prepared for his solo exhibition at Carriageworks.

Over cups of tea and fish soup, and in the company of his wife Aunty Liz, he shared his many stories of growing up on Erub (or Darnley) Island in the Torres Strait between Papua New Guinea and Queensland. Uncle Ken grew up alongside my father on Erub, and because of the generational difference, as well as inter-marriage dating back to the time of my great-grandmother, I call him “uncle”.

Since 2014, we have talked regularly about his work and travels and my own research and the many other things that take up our time. The recognition of his work today will reverberate for many years to come.

Machines for dance

Born on Erub in 1950, Uncle Ken moved to the Queensland mainland with his family at the age of 15. After working in the railways and in construction in Queensland and Western Australia he settled down in Cairns with his wife and their children.

Guided by his Christian faith, in the late 1980s he made the decision to form the dance group, Loza. Loza was also the name of a dance troupe his father, Tat Thaiday, once had on Erub. As the only son, Uncle Ken felt compelled to continue his father’s work. With the establishment of Loza, he taught the dances and songs his father had taught on Erub, and began to make dance objects or “dance machines”, mechanical moving devices that could be used as part of a dance.

The early dance machines were hand-held split bamboo clappers or marap and the now familiar dhari headdresses that adorn the Torres Strait flag and unmistakably identify each wearer with the islands.

Realising the content of the cultural storehouse of songs and dances he knew, Uncle Ken’s designs became more wide-ranging and complex. In his work he drew on his fondest memories of growing up on Erub and the teachings and life of his father.

Movable parts, and the human, animal, cultural, land and seascapes of Erub soon became standard features of Uncle Ken’s oversized works.

Neat, accurate figures of hammerhead sharks, fish and birds made from plywood or bamboo, were embellished with sharks’ teeth and fluffy feathers and painted with rich acrylic. The movable parts were connected by nylon fishing line and, by pulling on various toggles, dancers controlled the movements of the animals. In this way the wings of frigate bird masks can imitate flight and the shark can open and close its jaws.

Dance was integral to Uncle Ken’s upbringing on Erub. His deep knowledge of the sea, his experience and understanding of Islanders’ connections with the animal world and their cultural practices have shaped his artistic trajectory.

On the world stage

“How did your dance machines become art?” I asked him recently and he laughed softly. “Gallery people just started ringing me”, was all he said.

For Uncle Ken making dance machines as art objects fed the scale and audacity of his work, but they still came from the same place.

All I do he said, “is represent Erub. The Lord gives me skill and talent and what I do is from Erub.” It is in these messages that I believe the core of Uncle Ken’s artistic vitality lives and flourishes. “Erub is small”, he said “and my stories and dances are my truth. I can tell no other stories”.

By end of the 1990s, his artistic telling of his stories of Erub had propelled him onto the national and international art stage. His work is held in private collections and in numerous national and regional museums and galleries.

His achievements include artist-in-residence stints in Paris and Washington DC and his work has toured in group exhibitions to capital and regional centres in Australia as well as internationally to the US, New Zealand and New Caledonia and Europe.

In 2013, the Cairns Regional Art Gallery commissioned him to make a fully automated sculptural piece. The piece, a collaborative work with artist Jason Christopher, used aluminium and 3D printing technology to recreate Uncle Ken’s Hammerhead with clamshell (2000) dance machine.

The work is a three dimensional representation of a clamshell enclosing a hammerhead shark. When switched on, the clamshell opens to reveal the shark. Exhibition Manager, Justin Bishop described the work as “mesmerising, with its high tech finish and electronic componentry”, writing that it is “squarely located at the frontiers of contemporary art practice.”

Inspired by their 2013 collaboration Uncle Ken and Christopher worked on further exhibition pieces. For the 2016 Defending the Oceans exhibition at the Oceanographic Museum of Monaco, two five metre and an eight metre dhari were made and shipped in parts to be assembled at the museum. Back in Australia for the 2016 Biennale of Sydney, an automated aluminium-cast triple hammerhead shark dance machine greeted exhibition goers at the NSW Art Gallery.

As Uncle Ken continues to tell his stories and his truth, through his dance machines and other sculptural work, he continues to captivate and inspire. His work resonates with all Islanders because of its undeniable and evocative connection to and celebration of an Islander identity. It speaks to the adaptability and resilience of Islanders.

When I asked Uncle Ken what he thinks about when he looks at the work of other Indigenous artists – or wants to know about it – unsurprisingly he told me he likes to “ask about their meaning, to find their stories”. “We have stories about the same things” he said, “the land and the sea and us.”

I didn’t get the chance to ask Uncle Ken what advice he would give to up and coming Indigenous artists. But I imagine it would be something along the line of cultivating faith and telling your own truth.

Ken Thaiday’s work will appear among the work of 30 Indigenous artists at the National Gallery of Australia’s 3rd National Indigenous Art Triennial, Defying Empire, until 10 September 2017.

Leah Lui-Chivizhe’s article on Ken Thaiday Snr from was originally published on The Conversation. Leah Lui-Chivizhe is a lecturer at the Nura Gili Indigenous Programs Unit, UNSW.