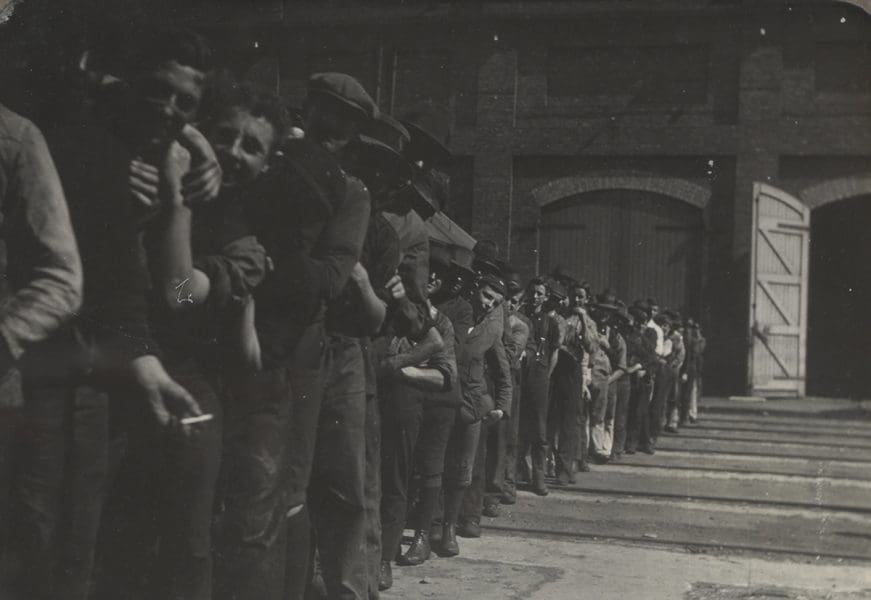

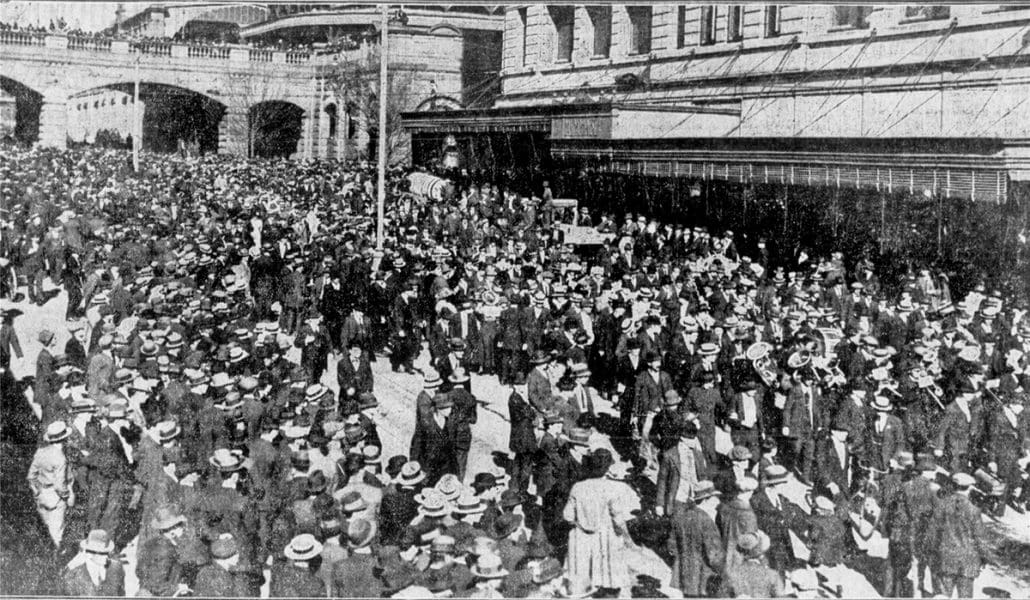

In August 1917, over 6000 working families from Sydney’s Eveleigh Rail Yards marched to the Domain, wearing straw boaters and Sunday shirts, to the tune of the labourer’s hymn ‘Solidarity Forever.’ A new time card system that monitored worker efficiency had provoked a groundswell of protest, resulting in a strike that avalanched from Eveleigh into the tram sheds, rail yards and docks of Sydney, and across other states. Over six weeks, 100,000 workers downed tools in one of the largest industrial actions of Australian history.

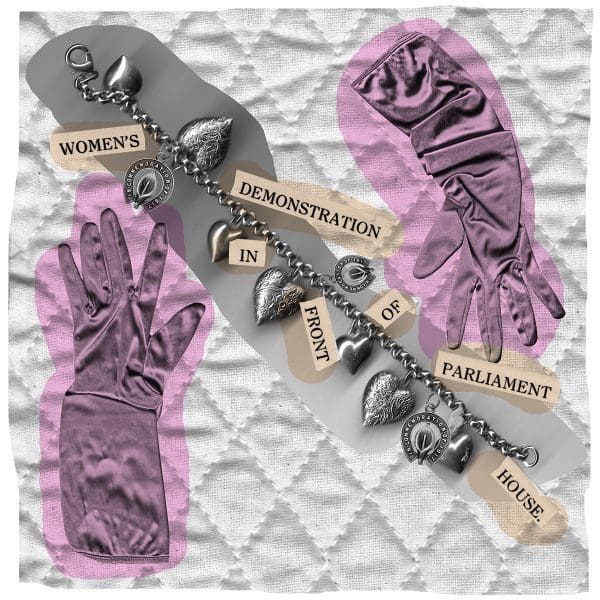

1917: The Great Strike will examine the spectacle and legacy of the strike, at the site of the former Eveleigh Rail Yards, now the Carriageworks arts precinct. Amidst a trove of historical documentation, aural testimony and union paraphernalia, artists Sarah Contos, Will French, Franck Gohier, Raquel Ormella and Tom Nicholson have integrated their responses to this history in a series of commissioned artworks. Springing from particular objects or sub-plots in the narrative of the Great Strike, their artworks will “reanimate its social history; the imagery of the trade union movement, the vital contribution of women and the notion of collective gathering,” says curator Nina Miall.

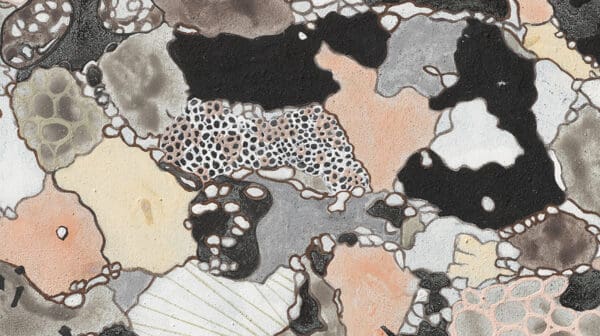

The Everleigh Railway Yards – designed by George Cowdery and completed in 1897 – contained a paint shop, carriage-building yard, telecommunications office, air raid shelters, gas works and a blacksmith. “The building bears the scars of its history,” Miall explains. “Train tracks run through it, there are tarnished surfaces, a deeply scarred concrete floor. It speaks to the grit and materiality of people doing hard manual labour here.” The surrounding inner-city suburbs of Redfern and Newtown are scattered with workman’s cottages, where local boys once made rounds on bicycles to wake up the workers on the early shift.

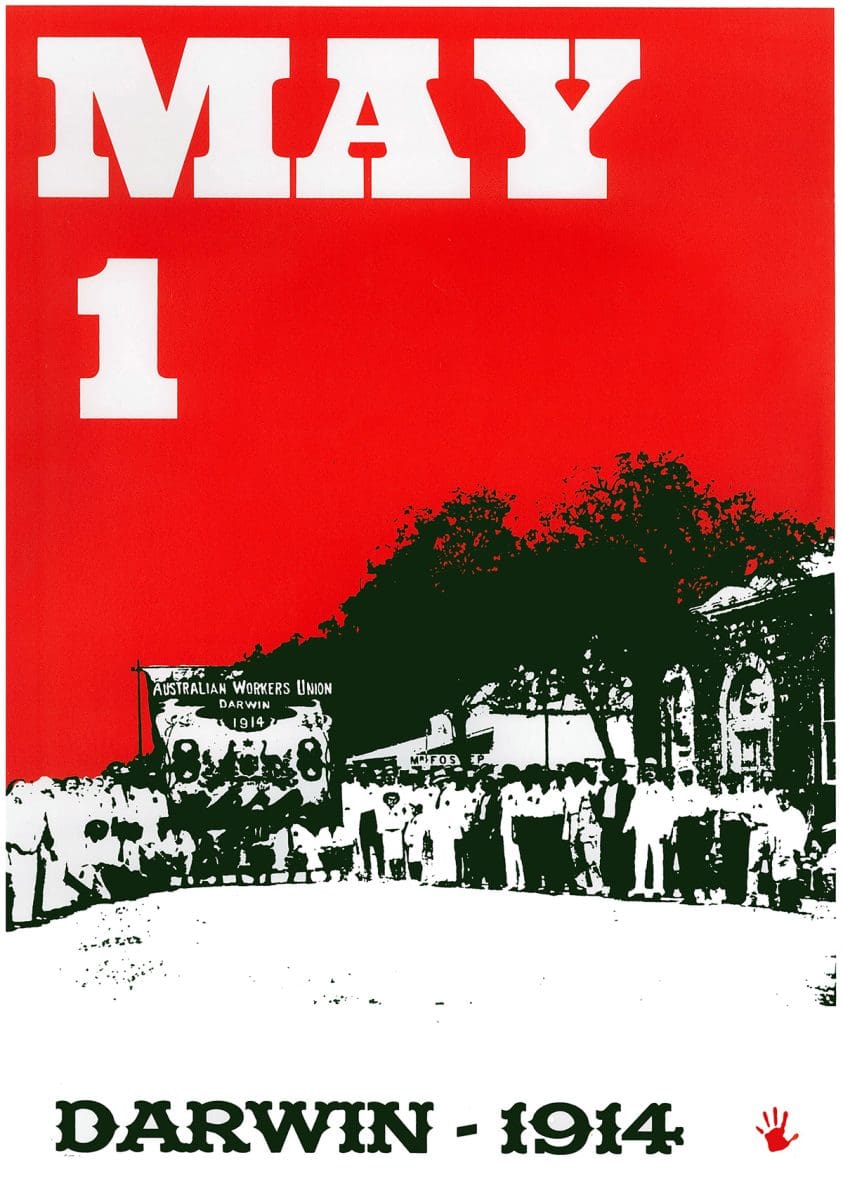

1917: The Great Strike includes archival photographs of the workshops in action, union banners, certificates, badges, cartoons, time cards and newspapers.

Visitors can listen to the aural testimonies of Sydney-siders who witnessed or participated in the strike. A particular coup is a film of the strike, shot in situ by one A. B. Tinsdale, which was broadcast once in 1917, censored, then partly mislabelled and effectively lost. In partnership with Simon Drake at the National Film and Sound Archive, the piece has been revived for its first screening in a hundred years. “It’s incredible footage,” enthuses Miall. “Women marching on Parliament House, protests in Wollongong, marches down to the Domain.”

A multi-site work by Melbourne artist Tom Nicholson considers the demonstration route between Carriageworks and the Domain. A pair of existing brutalist railway vents will be inscribed with texts that call upon readers to imaginatively reconstruct the bustle and scale of the strike, monumentalising the Domain as a site for collective action, “awaiting our deeds”. In both sites, the text will be accompanied by a musical soundscape penned in collaboration with New York-based Australian composer Andrew Byrne. “It will be a non-classical brass band work. The sound will be a dispersed field that you walk amidst,” Nicholson explains. For Nicholson, a former secretary of the VCA student union and picketer in the 1988 maritime strikes, the music, lyrics and atmosphere of demonstrative gatherings have a “potency that you remember for a long time. I want people to think about how action is prompted, which is something that we artists think about a lot.”

The hundred-year impact of the Great Strike can be traced throughout Australian history. Train driver Ben Chifley and yard worker Joseph Cahill were moved by the strike to enter politics, becoming the Prime Minister and Premier of New South Wales respectively; strikers and scabs remained socially driven for decades; and that part of the Australian self-image which speaks of camaraderie, the nobility of a fair day’s labour and work-force solidarity, were burnished for posterity.

The strike itself was widely considered unsuccessful; its spontaneity left workers exposed and with little means of negotiation.

“It was cooked from the ground up,” explains Nicholson. “It lacked strategic planning.” The consequences were “devastating,” says Miall. “Many were demoted, others lost their jobs completely.” A hundred years on, the strike of 1917 has been succeeded by forms of dissent that play out in isolated union groups, online, anonymously or in the media.

“I hope the exhibition will generate debate,” says Miall. “In the Great Strike, 100,000 people marched every Sunday for six weeks. We think that this is equivalent to 750 million Sydneysiders today. In 1917 there was great pride in the act of demonstration. The street was a theatre where urban life played out.”