Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

When journalist and editor Jules François Archibald left one tenth of his estate in trust to fund an annual portrait prize, did he envisage that it would still be running a century later? It’s possible. After all, people who leave large bequests tend to be thinking of their legacies. But it is unlikely that he could have imagined the unique place that the Archibald Prize has come to hold in popular culture. And it is almost inconceivable that the man who the Archibald is named after could have foreseen that the winner of the 99th prize would be an Indigenous artist, or that in its 100th year the prize would achieve gender parity for the first time, with 26 of the 52 finalists being women.

To mark the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Archibald Prize, Art Guide asked 10 Australian artists to each choose a past winner, one from each decade. Their choices form a fascinating snapshot of a prize that – by highlighting who is sitting for which artists (as well as who isn’t being represented on either side of the canvas) – continues to paint a portrait of a changing nation.

Ben Quilty, one of Australia’s best known painters, has had his work hung in the Archibald Prize multiple times. In 2011 he won the prize with his portrait of Margret Olley, and this year he is in the Archibald as the subject of Mirra Whale’s portrait, Repose.

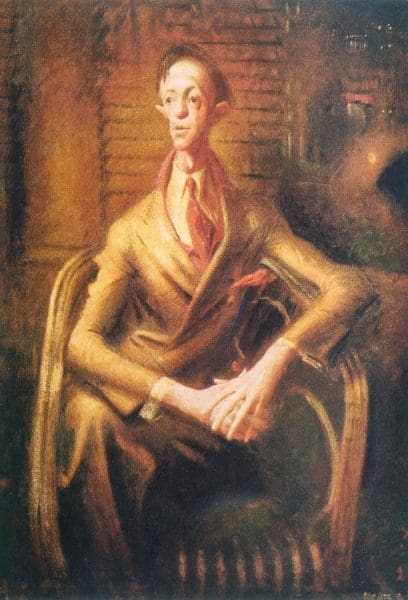

Quilty chose Portrait of a Lady, 1923, by WB McInnes. The lady in question was the painter’s wife – an artist in her own right – and Quilty sees this choice as a subtle act of defiance.

“This was a period of ultra-conservatism in Australian culture. The White Australia Policy was forming national identity. McInnes gently breaks the rules with this tender portrait of his wife. “The Archibald rules state that sitters should be ‘preferably from letters, the arts…’ etc,” Quilty explains.

“I’m personally interested in human stories, human frailty, love, sadness, loss and joy. McInnes was criticised for making a portrait of his wife, and not someone famous for the culture-hungry public. I am intrigued by the time these two artists sat together,” he says. “For me it’s an homage, a quiet ode to the love they share, perhaps!”

Although the mainstream Australian culture at the time many have been conservative, Quilty points out that the Archibald entries aren’t all white men. “Surprisingly,” he says, “there were several women sitters, and the first Indigenous sitter, David Unaipon, appeared on the walls of the show. It was a far more sophisticated decade than the years following the First World War.”

Peter Burgess, a cross-media artist known for making the most of industrial technologies – from digital printmaking, to CAD cut wall drawings and 3D printed objects – has never entered the Archibald Prize.

Burgess selected Max Meldrum’s portrait from 1939, Hon GJ Bell, CMG, DSO, VD (Speaker, House of Representatives). Meldrum also won in 1940.

“I have long been a fan of Max Meldrum’s work. Who doesn’t love an artist that rejects the dominant mode of art teaching of their day, writes their own theory on art and establishes their own art school,” Burgess says. He adds that Meldrum’s “scientific approach to tonal painting” was influential: Clarice Beckett and Colin Colahan (who was hung in the Archibald several times) were among his students.

According to Burgess, Meldrum’s decision to paint Bell was a reflection of current affairs. “The Archibald Prize 1939 was exhibited from 20 January to 20 March 1940. On 3 September 1939, every radio station in Australia carried Prime Minister Robert Menzies’s announcement of Australia’s beginning involvement in the Second World War. Meldrum’s choice of subject was an astute one, as Australia rested at the edge of War,” says Burgess. “Bell had been a decorated Light Horseman during the First World War. Meldrum’s choice of subject was no accident.”

The portraits in the decade 1931-1940 were mainly of ‘distinguished’ men, Burgess notes. “It was an age of letters, abbreviations and acronyms: esq, Hon., MLA, GCMG, KCB, MD, etc.”

Joan Ross, an artist who says she works with “most mediums,” including video animation, virtual reality, painting, drawing, and sculpture, has had her self-portrait Joan as colonial woman looking at the future hung in the 2021 Archibald Prize. And Tom Polo’s portrait of her was hung in 2018.

Ross chose the 1943 winner, William Dobell’s Mr Joshua Smith (Portrait of the Artist). “This was the most exciting year of the entire Archibald Prize, in my opinion,” she says.

Dobell’s painting sparked a furore. His depiction of Smith was lambasted and accused of being a caricature rather than a portrait. Ross describes Dobell’s win as “the biggest game-changer in all Archibald history. It caused so much controversy in the establishment, which hurt Dobell personally. But it paved the way for marked change, and after that more contemporary works were entered and accepted into the Archibald Prize.”

For Ross, deciding which portrait to choose from the decade 1941-1950 was easy. “There was so much brown! And so many men,” she says. “It was end of war times, lots of suits and uniforms. And apart from both the Dobell portraits from that period, including his great well known painting of Margaret Olley, they were just so conservative!”

Hayley Millar Baker is known for her narratively dense black and white photographs which are concerned with constructing memory, remembering and misremembering, inheritance of memory, and the inheritance of storytelling. She has not yet been in the Archibald as either artist or sitter. “But,” she says, “it has always been a goal of mine to one day submit a painting.”

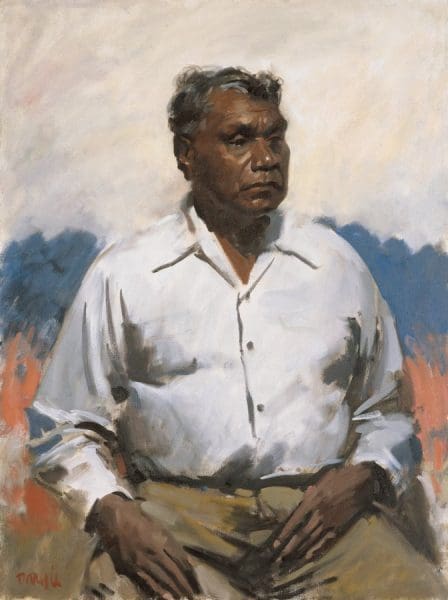

Millar Baker chose William Dargie’s 1956 portrait, Mr Albert Namatjira, the first portrait of an Aboriginal person to win the Archibald. “Since then,” she notes, “only three more portraits of Aboriginal people have won the prize.”

Millar Baker explains that she was drawn to Dargie’s ability to capture the artist’s enigmatic expression. “Namatjira gazes away from the painter, expressionless, but very clearly deep in thought. The viewer can only guess what he is deep in thought about, but his gaze is captured incredibly well by Dargie,” she says.

The portrait of Namatjira also stood out, she explains, because the decade 1951-1960 was “saturated with portraits of white men: white men sharing smug expressions, expressions of confidence, and expressions of self-awareness.”

Alex Seton, a sculptor who works primarily with marble, had his portrait painted for the Archibald for the first time this year, but the work was not selected. He is yet to have his own work hung. “I’ve attempted a few times to no avail,” he admits. “The earliest was when I was only sixteen, with a lamentable portrait of actor John Bell who was very kind to my spotty teen-aged self.”

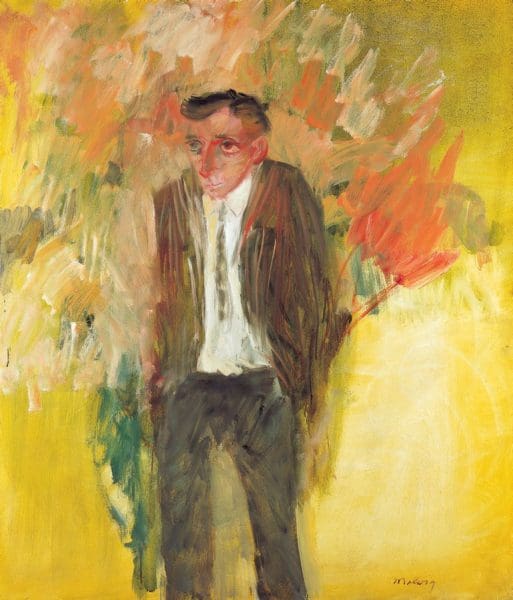

Seton selected Jon Molvig’s 1966 painting of fellow artist Charles Blackman. He was attracted to the way Molvig captured “the physicality of the sitter, not his facial features as such.”

And in addition to the physical characteristics of Blackman, Seton points out that Molvig seems to have caught something of Blackman’s personality as well. “The hunched, slightly demure stance with hands forced into pockets speaks to me of humility and the discomfort of the fuss; the embarrassment of being the subject of the portrait,” he explains. “You can feel the affection of Molvig for his sitter in his rendering of the whole body, unlike the many examples of technical formal facial portraits in that decade.”

Seton found 1961-1970 to be loaded with “incredibly earnest white men painted in classic three-quarter pose.” He notes that Judy Cassab’s portrait of Margo Lewers “breaks the monotony of XY chromosomes,” but he adds, “it subscribes to the same format unfortunately.”

Janet Laurence, who is known for her large scale mixed-media installations which often include natural materials and focus on environmental issues, was the subject of a portrait by John Beard that won the Archibald Prize in 2007.

Laurence chose Kevin Connor’s 1977 portrait of sculptor Robert Klippel. “He’s consistently been a great painter,” she says, “and has grasped the gestures and personality of Robert Klippel.”

Klippel (who died in 2001) lived and worked in Sydney, and Laurence, who also resides in the city, had made his acquaintance. “The portrait integrates the figure into the surrounds and ground, which Connor has kept so spare so that all the focus is on Klippel’s face and eyes which I remember were very penetrating,” she says.

Laurence notes that in the decade 1971-1980, only one woman won the Archibald Prize (Janet Dawson in 1973 with a portrait of her husband Michael Boddy) and all of the sitters in the winning works were male. “As the Archibald will always remain traditional,” she says, “it would be great to complement it with a contemporary portrait exhibition.”

Jon Cattapan, a painter whose signature work captures the metropolis as a zone in constant flux, has never entered the Archibald Prize. But his portrait was hung in 2016. “I was painted by my young friend Ben Aitken in Portrait of Mentor (Jon Cattapan and Self),” he explains. “It is a very good sly double portrait.”

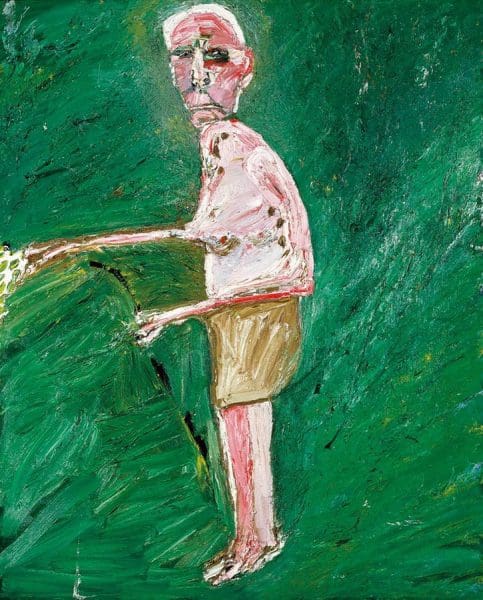

Cattapan selected Davida Allen’s 1986 portrait of Dr John Arthur McKelvie Shera. “For me, the strength in Davida’s work is twofold. Hers is a gusty expressionistic type of painting often associated with a certain ‘machismo.’ But her subjects subvert this attitude nicely,” he explains. “Very often domestic in nature, in her works there is a direct intimacy and honesty about what she chooses to represent. This is the case in her Archibald entry, a portrait of her father-in-law engaged in the very simple backyard pleasure of watering his trees.”

“Most of the portraits in this decade are by men and of men,” says Cattapan. He also points out that the decade 1981-1990 started with a legal battle. “In 1981, Eric Smith’s winning portrait of Rudy Komon was thought to have been based on an old photograph – apparently a big no-no.” The court case affirmed that Smith’s win was legitimate.

Times have changed. Whereas in the past it was assumed that portraits should be painted entirely from life, these days the rules require ‘at least one live sitting with the artist.’ As Cattapan says, “It would be inconceivable now to bring into question a work’s validity because photographic sources were used!”

Laresa Kosloff, an artist and activist known for video, audio and performance works infused with both dark humour and political acumen, has never entered the Archibald Prize. “Although I studied painting I gave up after a few years and took up video art,” she says. “I could never make aesthetic decisions as a painter, it felt too arbitrary to me.”

Kosloff selected Nigel Thomson’s portrait of Barbara Blackman from 1997. “I like the way that this painting explores the sensation of touch through the painted surface, depicted objects and the elderly blind woman,” she says. “This painting is also about being in a body over a long period of time, and the habits and psychology that form throughout a lifetime. For me, this painting stood out from the others as it offers more space for contemplation.”

Kosloff notes that Barbara Blackman had been married to the well-known Australian painter Charles Blackman. “I think about the wives of famous historical painters, and how they cared for the children and kept everything together in the background. I think about their unsung wisdom, their tact and patience,” she explains, “how they put up with the intoxicating attention that their husbands received and their obsessive creativity.”

The influence of postmodernism was obvious in her allocated decade, Kosloff says, but she couldn’t resist looking further back. “Scrolling down the historical portraits I was struck by the number of proud and entitled white men in the archive,” she says. “It made me think about how we naturalise the conditions of our own era. We internalise the power structures, patriarchy and bias in unconscious ways. Although the arts can play a role in questioning a cultural status quo, they can also serve to reinforce it.”

Kenny Pittock, a sculptor and painter known for putting his own cheeky spin on pop art, says that he has entered the Archibald a couple of times, but has not yet been selected. He adds that he has also had his portrait painted for the prize, but then admits “technically, it was a self-portrait.”

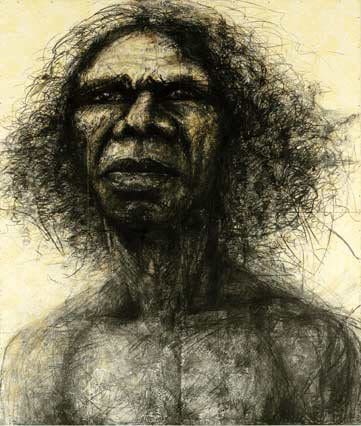

Pittock chose Craig Ruddy’s winning work from 2004, David Gulpilil, two worlds, which caused some consternation with its resemblance to a drawing.

“Apparently Paul Klee said that ‘Drawing is taking a line for a walk,’ but in this painting the artist takes the line for a marathon, totally pushing the limits of what can be achieved in line drawing,” Pittock says. “There’s an energy and empathy in this painting that I find almost too difficult to pin down, or maybe just too moving to put into words.”

Pittock found plenty to like in the decade 2001-2010, and he nominated Guy Maestri’s 2009 portrait of Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu for a honourable mention. “I love this painting for a lot of reasons,” he explains, “but actually the main one is that it introduced me to the amazing life of Gurrumul, whose music can now so often be heard playing in my headphones while I work.”

“There were a lot of great paintings made in the 2000s. Thank goodness that 1999’s Y2K bug didn’t end the world and so we lived to see them,” Pittock says. “That being said, during this decade only two of the 10 winning subjects were women, and only two of the winning portraits were painted by women – despite many worthy entries – so there’s still obviously lots of room for improvement.”

Larrakia/Wardaman/Karajarriartist Jenna Lee, who works primarily with paper, text and language to make sculpture and installation – but also works with film and projection, has never entered the Archibald Prize. “I am definitely not a painter,” she says, “and would feel quite lost in front of a canvas with paint.”

Lee selected the 2020 winner Vincent Namatjira’s self-portrait with Adam Goodes, Stand strong for who you are. “When I look at this painting I feel pride at seeing two of our men standing so strong, being completely outstanding and exemplary in their respective fields. I see phenomenal moments from both of their careers that have had an impact on this country as a whole. I see a witty and timely message we needed in 2020 and I see an excellent painting by a master,” Lee says.

“I also feel hurt and pain for everything our community continues to endure and sadness at the fact that in the history of the Archibald Prize, Vincent Namatjira is the first Aboriginal artist to have won. With 60,000 years of art-making history on this land, I hope to see many more.”

After taking 99 years to award the prize to an Indigenous artist, Lee looks towards the future. “In the most recent decade of the Archibald prize I have noticed an increase in representation of women, not only as subjects, but as painters. I see moments of forward movement, with a portrait of Lindy Lee, a prolific Chinese Australian artist as subject directly followed by an Aboriginal man as subject and painter,” she says. “I am starting to see glimpses of a prize that could reflect the diversity and multiculturalism which makes Australia and its art scene globally unique. If anything, I see hope that the next decade of winners will reflect and celebrate the faces of people who have long been unseen in this country.”

Archie 100

MAGNT

Until 26 June 2023

Please note: The Archibald, Wynne and Sulman Prizes can be viewed on online as a 360-degree virtual exhibition. And for more things Archibald, check out the AGNSW Archie at Home program.