Tricky Walsh‘s exhibition Flatland, at Devonport Regional Gallery, is a scientifically and philosophically rigorous engagement with questions regarding reality, perception and dimensionality. With rich colourful paintings and intricate sculptures, Flatland is in part a response to recent developments in the dauntingly complex but fascinating holographic principle, a strand of string theory. It also takes a cue from Edwin A Abbot’s satirical 1884 novella Flatland in which characters are merely geometric figures in a two-dimensional world. Barnaby Smith spoke with Walsh about multiple dimensions and the limitations of knowledge and experience.

Barnaby Smith: When a visitor walks into Flatland, what will they see?

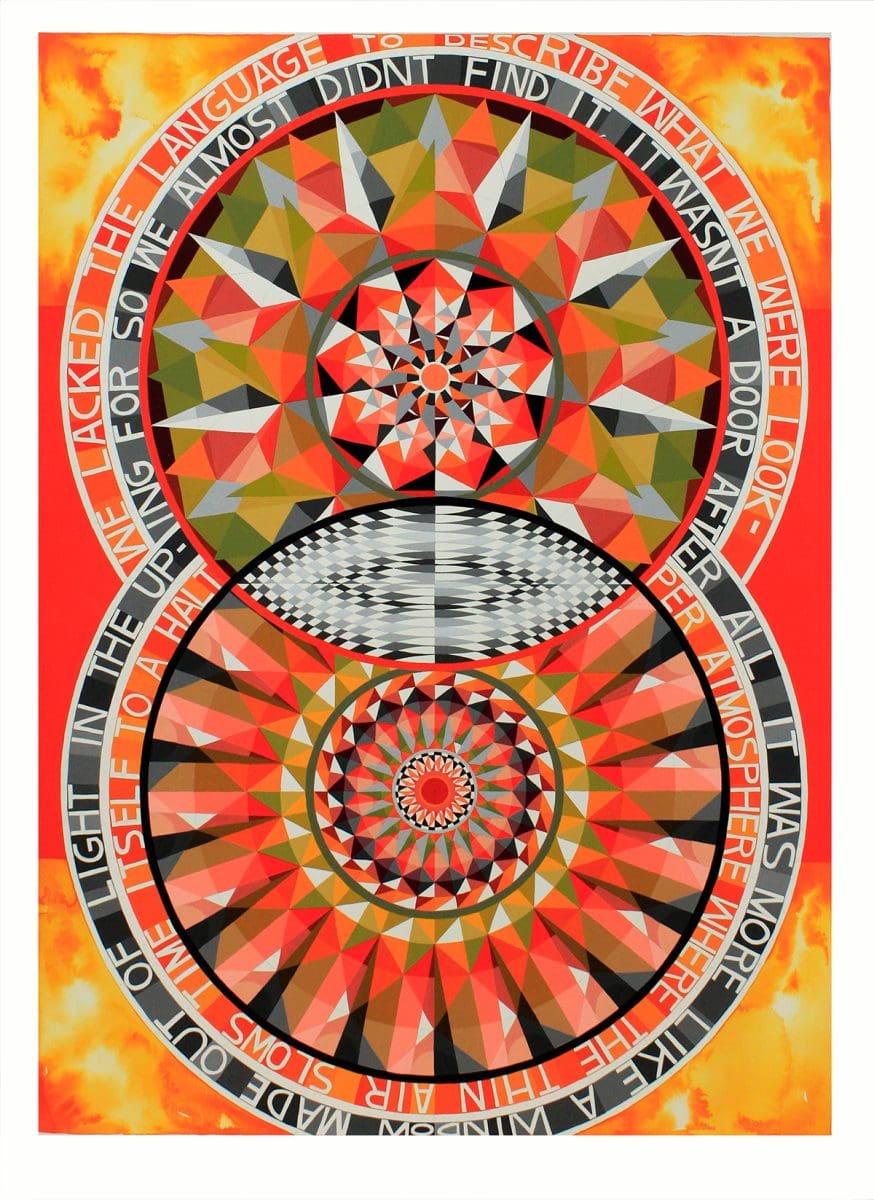

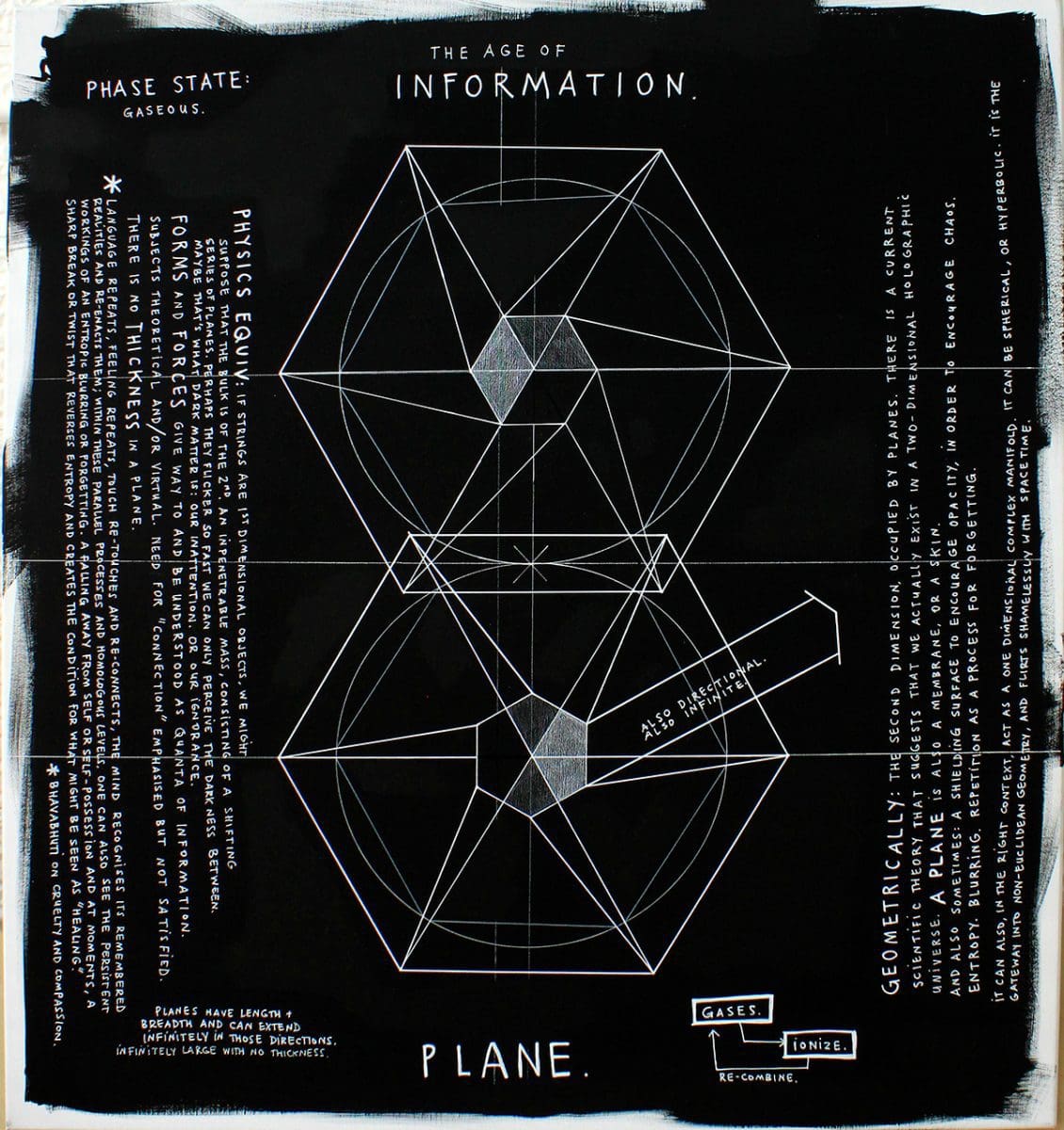

Tricky Walsh: In the centre of the gallery is a set of sculptures made primarily from timber, which look like machines or scientific instruments. On the walls, colourful geometric paintings sit among diagrammatic black and white blueprints that are covered in text.

BS: What, in your understanding, is the holographic principle, and why did it fascinate you to the point that you made these works?

TW: I was looking into the idea that we would soon be discovering a new dimension – possibly as many as eight. I was fascinated by whether they would be extra spatial dimensions or time ones, and what that would mean for us.

Alongside this, they had started talking about the holographic principle which, to my mind, is basically stating that actually nothing in our universe or experience is actually solid, but more like a shifting series of flat-plane images which, much like film stock (rapidly moving still images that make us perceive movement and space), construct our visual sense of three-dimensionality and solidness.

BS: What did you take specifically from Edwin A Abbott’s novella Flatland to inform this exhibition?

TW: The idea that we were like those two-dimensional characters, just profoundly unable to see beyond what we know. The thought that there might be a more complex visual or other kind of experience, and what that might entail, was my primary departure point.

The rampant classism and sexism I could have done without, but you know, ‘the times.’

BS: Some of the works in Flatland incorporate text. Where do these words come from and what was the intention behind using them?

TW: Mostly as triggers, I suppose. Some have come from things I have read while working on the show, particularly poetic strings of words that I have taken out of context as a means for provoking ideas or questions. Some of them are mine; I enjoy text as a medium. I rarely use it to explain, but more as a ‘Hey, what’s that over there?’ kind of augmenting device.

BS: Your work has crossed many mediums. Why did the ideas explored in Flatland best lend themselves to painting rather than something else?

TW: There are both paintings and sculptures in the exhibition. But generally, I always see my paintings as a kind of blueprint for objects, even tenuously. And sometimes I find the proposition of movement, or of sound, more effective than the actual things themselves.

You can do a lot with colour and form to suggest a response in people, but they have more agency than being passively fed information. They get to finish the sentence. Which I think is important right now – encouraging a more active viewpoint.

BS: The idea of ‘systems’ appears to be a consistent theme in your ongoing body of work. Can you describe what systems mean to you in an artistic context, and where this interest comes from?

TW: Systems are fundamental. For me it is always about connectivity. I grew up with electrical nerds, so the idea of the circuit has always played a significant role in what I make.

Nothing progresses effectively in isolation. I also like the variables that are introduced when you make things rely on the presence of other disparate things – it’s like injecting some chaos into the equation.

BS: Visitors to the exhibition might not detect a great deal of political or social comment in these works. Is that fair to say, or is there an underlying ideological thread?

TW: It’s true that the exhibition does not follow any overt political or social commentary in a language that is easily recognisable, but it exists.

The Ana-katascope, 2018, for example, is an invitation to collaborate. It uses the scientific concept of the observer principle (where things that are observed are inextricably changed as part of the process of being observed) as a proposition for working collectively in order to achieve a consensus.

To be able to see all facets of an idea, or a thing, or a question, that discussion and debate is an inclusive model for resolution, I suppose. Whether this is detected or not, I can’t say, but the intent is there.

BS: Which other artists exploring the nature and science of dimensionality have had an influence on your work?

TW: Most of my work tends to speculate rather than inform, so I feel an affinity with artists such as Suzanne Treister. But mostly I find myself poring over texts from the 19th and 20th centuries, when people were more free to investigate the fundamental building blocks of our world: Walter Russell’s 1927 book The Universal One; Charles Howard Hinton’s work on the tesseract and his writings on the fourth dimension; James Maxwell’s work on optics.

I’m not so sure that we’re finished looking at them, even though the compulsion to accept and progress is such a defining human trait. I guess I’m more excited by the work of people who could see an innate connectivity between fields: mathematics and philosophy, electromagnetics and optics.

BS: With Flatland responding to recent developments in science, do you consciously keep up with scientific news for ideas?

TW: Yeah, I do. But I also spend a lot of time looking back as well, at the lineage of discovery and especially at the paths not taken. I’m interested in the point at which we divert and what we leave behind; where it might have taken us instead.

Flatland

Tricky Walsh

Devonport Regional Gallery

28 September – 17 November