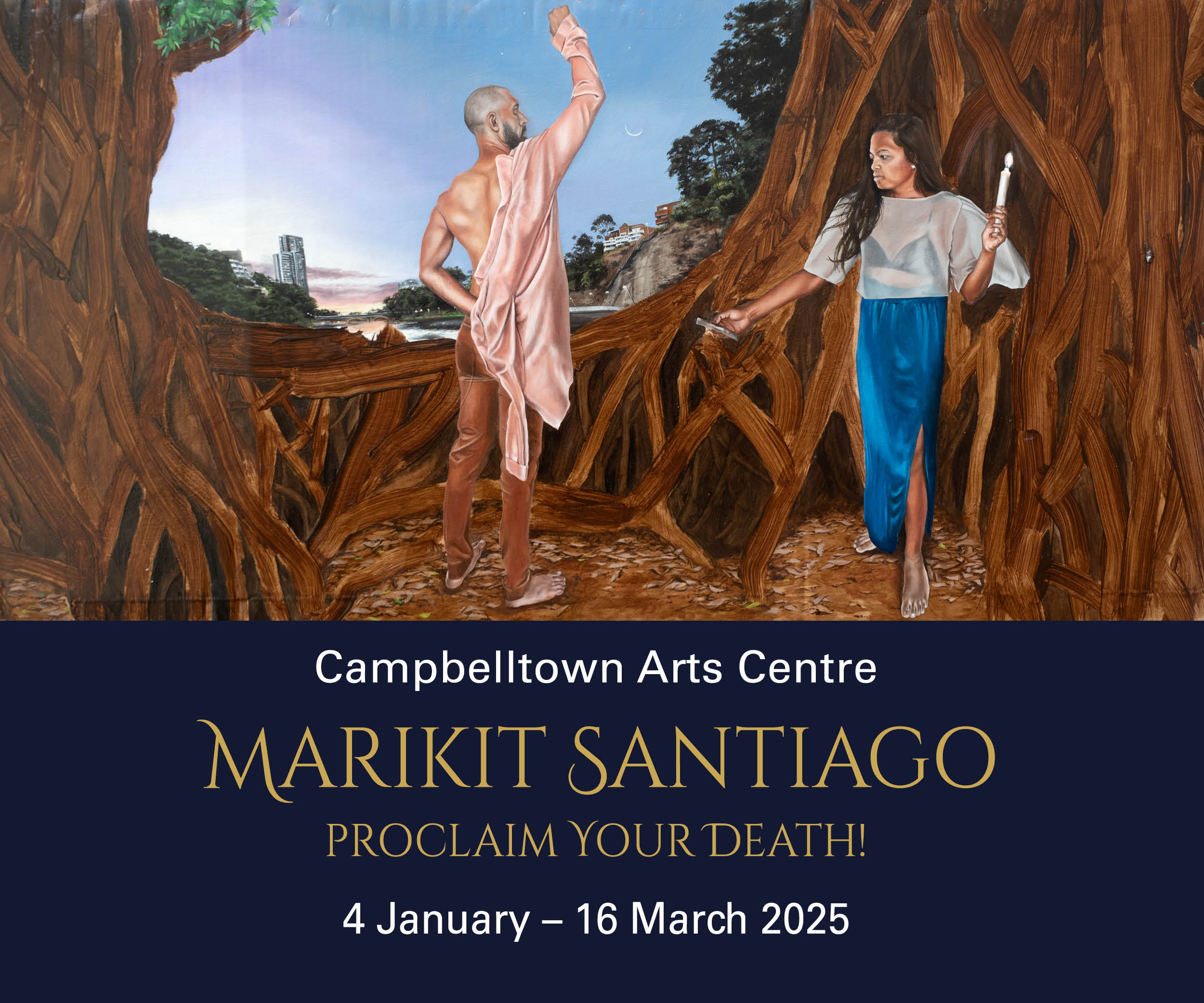

Lost in Space: A Conversation with Cao Fei

Luise Guest speaks with internationally acclaimed multimedia artist Cao Fei—whose work is on show at the Art Gallery of New South Wales—about why the city is a repository of memory and the power of the places we forget or overlook.