La Belle Èpoque in Bendigo

A new exhibition at Bendigo Art Gallery, drawn from the Musée Carnavalet in Paris, brings the Belle Èpoque era to life through impressionist paintings and antique ephemera. View, in pictures, a slice of Parisian history.

Different shades and nuance mark Girramay and Kuku Yalanji artist Tony Albert’s family. His father is from the Rainforest people, who cover several language groups in Far North Queensland, and served in the army. His mum is a white Australian.

Born in Townsville in 1981, Albert has lighter skin than that of his younger sister, Tina, and when the family relocated to Brisbane, where Tony and Tina attended primary school, she was teased more, because of her darker appearance.

“I couldn’t understand why, but they obviously didn’t realise I was Aboriginal until a big black man came to pick me up. I still can’t fathom that way of thinking.

“My first day at school, my mother was asked: ‘Oh you’re working already? … You’re the nanny of these children?’

“That’s less of a story that’s spoken about: a white mother with brown children. Only recently we’ve started opening up to these characters in the media, on TV and in the movies.

“As a big brother, I was very mindful of the implications of my sister having much darker skin. We were the only Aboriginal children in our school, but I remember my sister, more so than me, having Pacific Islander friends.”

The artist sports a red hoodie top and gingery stubble. He relocated to Sydney five years ago, deciding to stay after coming south for a six-month residency, although he spent the second half of 2015 in an artist’s residency in Brooklyn.

Albert can imagine living in New York, given his love of pop culture – he idolised Batman growing up via the 1960s TV series – and the sheer density of cultural inspiration on offer. He made a pilgrimage to the Dollywood theme park in Tennessee, seeing Dolly Parton perform, before driving to New Orleans.

There are no plans to move overseas, however. The day we meet, Albert is moving house in inner-western Sydney, from one end of King Street to the other. He’s been working all year as an artist-in-residency at Alexandria Park Community School, a “very heartfelt” pilot project.

“I want artists to be in every single school in New South Wales,” he says. That ethos can be seen as an extension of Albert’s democratic ideals: a member of Queensland’s proppaNOW collective since 2003, he gained a profound understanding of Indigenous politics as a studio assistant to Brisbane-based Indigenous artist Richard Bell.

Curator Hetti Perkins has written of the powerful political statements Albert makes, referencing a group work, Pay Attention 2009–10, for which Albert assembled artists, from desert Aranda potters to western Cape of Queensland sculptors, giving “expression to this pluralism” while advocating a “subversively propagandist agenda”.

Albert smiles when I read the quote and ask if he considers himself subversive. “I hope so,” he says. “It’s funny for me, because I always think I’m the quiet, shy one.”

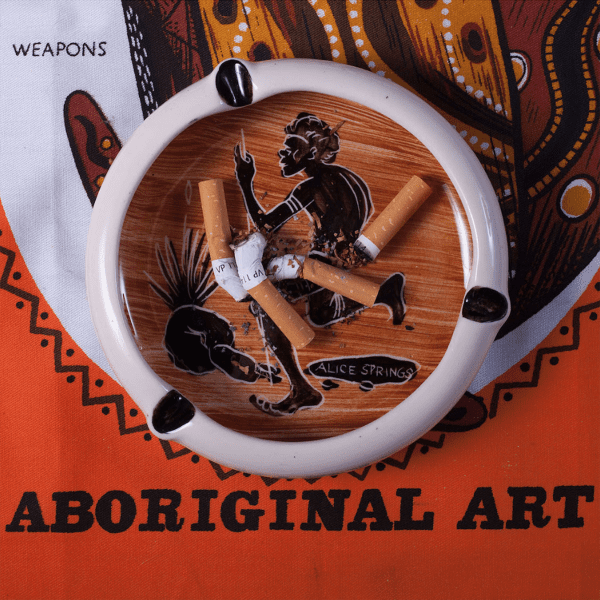

His latest solo show, Unalienable, is an extension of his previous work co-opting kitsch Aboriginalia, Ash on Me, including faces of Indigenous people on ashtrays.

His family had a low income, so Albert shopped in opportunity stores, and buying this memorabilia became a way for him as a boy, and then a teenager, to understand his own identity.

“I loved them; I thought these were beautiful objects that had people on them who were in my life,” he says. “These were treasures to me; I loved the storybooks with little Aboriginal characters. They appealed to me from a very innocent perspective.”

The images, drawn by non-Aboriginal people, were naive about Aboriginal lives, but not ill-intentioned, Albert believes, even as the books, comics, plates, cups, saucers and ashtrays were pressed into a more broadly problematic schema of racial politics.

Brownie Downing’s Tinka storybooks and porcelain plates, for instance, depicting an Aboriginal boy character, “were very much this love affair with the magic of the bush, like May Gibbs’s gumnut babies; the mystical notion of the Australian outback. I don’t think [Downing’s Tinka] was done with the idea of how problematic it is”.

When Albert exhibits outside Australia, many of his works take on a different meaning. His photos of teenage boys with targets painted on their chests, for instance, are, in the US, seen not as metaphorical representations of Indigenous Australian youths shot by police in a stolen car in Kings Cross, or the remote communities intervention targeting Aboriginal men.

Instead, the works are seen in the context of the African American movement that formed in the aftermath of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin’s fatal shooting by a white man in 2012: that Black Lives Matter.

Unalienable

Sullivan + Strumpf

3 September – 1 October