The livre d’artiste, or artist’s book, as a collaborative art had its naissance in Paris in 1900 – while William Blake (1757-1827) is probably the progenitor of the genre, his works were not collaborative. It was in Paris that Ambroise Vollard, an art dealer, released a book featuring the poetry of Paul Verlaine, illustrated with lithographs by Impressionist painter Pierre Bonnard. Previously, book illustration had been a meagre addition to text, an afterthought. Arguably, the original artworks in an artist’s book – lithography, etchings and woodblocks – outweigh the importance of text.

Susan Millard, special collections librarian at the University of Melbourne and curator of the upcoming exhibition, Art on the Page at Noel Shaw Gallery, told Art Guide Australia that the show “focuses on pairing with text. Mainly poetry, but not always.” An artists’ book doesn’t necessarily call for such a clause in its definition. The form is not fixed, and even the vocabulary for describing the relationship between word and image is underdeveloped, or so wrote Breon Mitchell, professor of comparative literature, in 1976. Artist’s book are hard to pin down, belonging in a space perhaps between a library and an art museum.

A heavy antique table in the inner sanctum of the special collections library is laid out with publications that will be featured in the show.

The room is slightly cool and artificially lit, the shelves crammed with tomes. The reassuring smell of leathery books hangs in the air. Millard picks up the books with measured hands, opening them to favourite illustrations or pages that will be displayed in glass cabinets. “Some of these are a bit decimated because things have been framed,” says Millard. Books that are not bound in traditional codex form lend their individual pages to gallery framing. Several of those that don’t, such as the Lissitzy and Mayakovsky collaboration, For the Voice, 1923, are accompanied by interactive swipe screens to give viewers a look beyond the displayed pages.

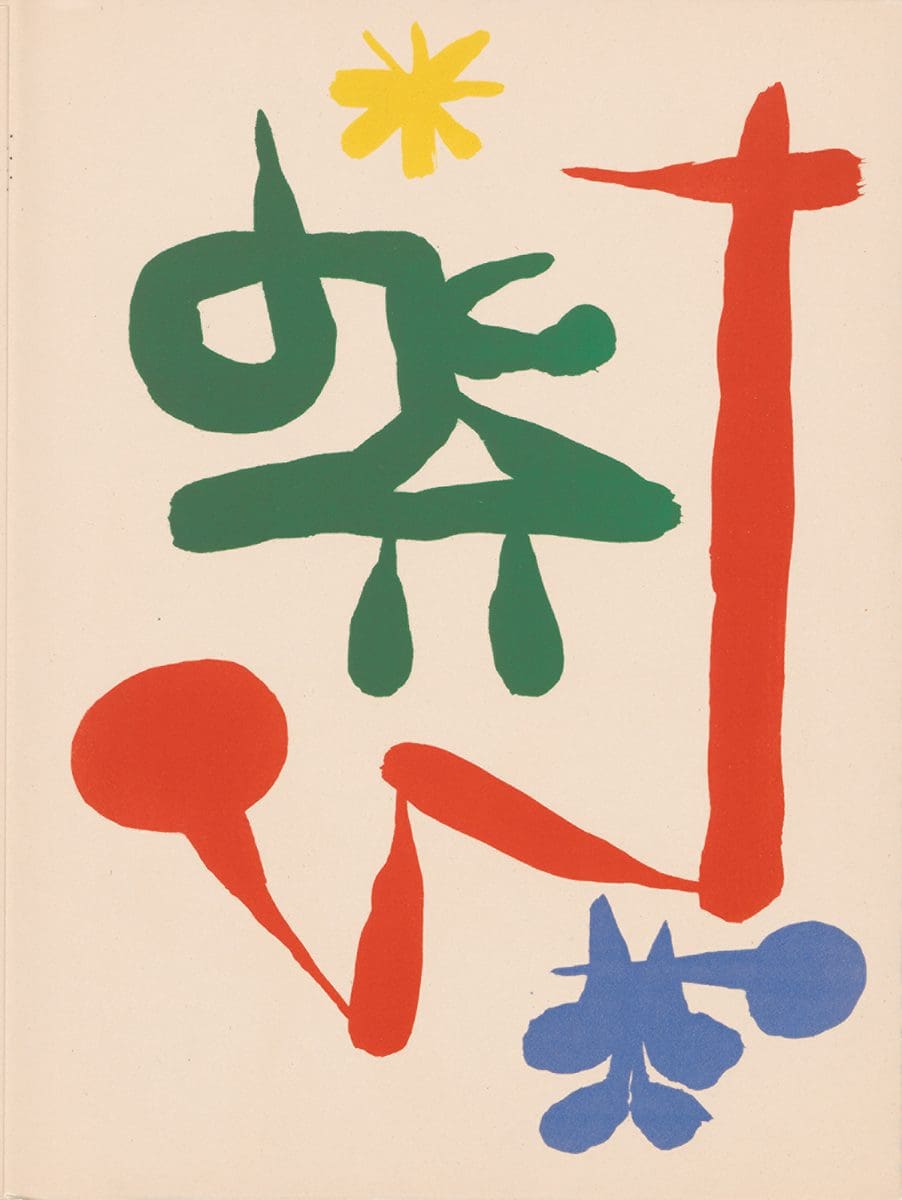

The core of the exhibition is early to mid 20th century European artists’ books – just about every major player of that époque – Picasso, Miró, Delaunay, Tápies, Dubuffet, Matisse, had collaborated on a book. All these listed are included in the show.

Paris in the first half of the last century, “was just this explosion of creativity – it was quite extraordinary. And it was the first time where artists and writers actually came together.” The attraction to the form, says Millard, was “instead of just painting the artists got to play around with the object of a book.”

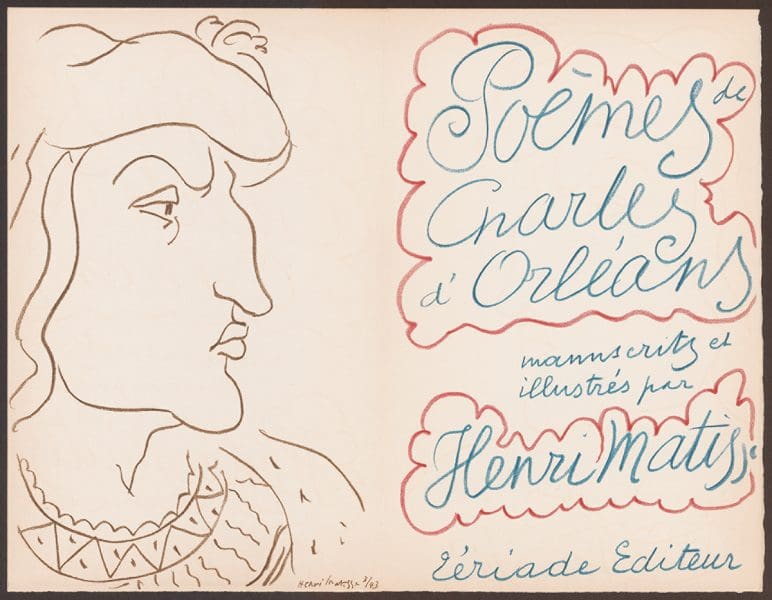

Millard proceeds to open Poèmes de Charles d’Orléans, illustrated by Matisse in the early 1940s when he was recovering from an operation. “Charles d’Orléans is a fabulous character, he was captured in the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 and taken as a prisoner to England.” Matisse decorated the pages in simple, freehand fleur-de-lis patterns.

The exhibition also looks to how the European tradition influenced Australian artists. “It seemed that at the time, modern Australian artists didn’t really take up the book form, it wasn’t really until the last few decades that that’s really happened in Australia,” says Millard.

One of the artists who brought the tradition here was Petr Herel. “He’s Czechoslovakian but was also in Paris, and he came out to Australia in 1973 and got a job as the head of the graphic investigation workshop in Canberra in 1979. He is highly influential because he taught a lot of students and then they went out into the world.”

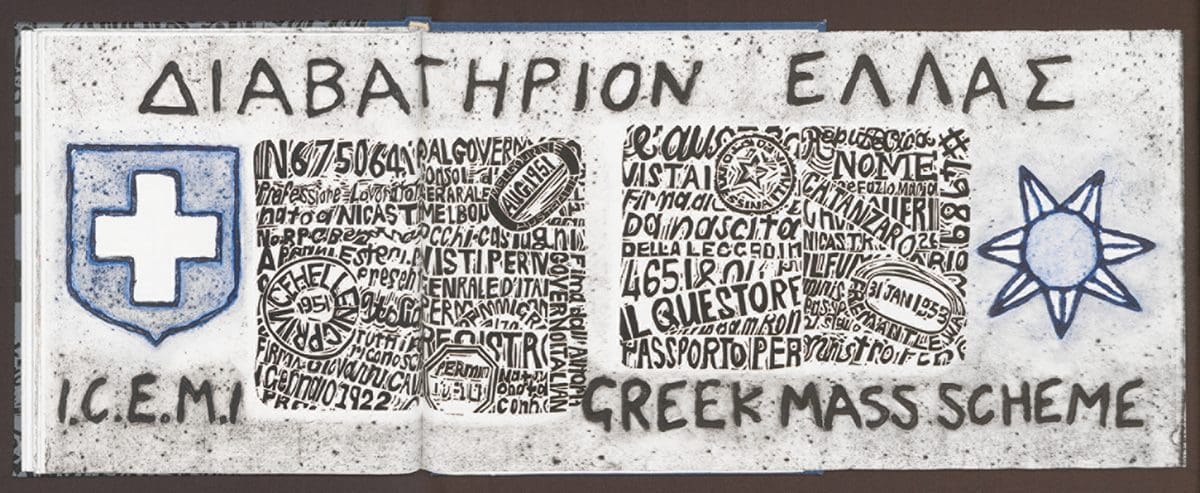

Millard picks up Europa to Oceania from the table and folds out a print. In the top corner, there is a print of a postage stamp depicting a passenger ship; underneath it is a churning blue ocean of text.

Over the top of the ocean in black, is a description of a voyage from Greece, ‘Avles 1961 Melbourne.’ “This is Angela Cavalieri, George Matoulas and Antoni Jach who did the words for this. And this is once again about the immigrant story.”

Theo Strasser is another book artist that is a transplant to Australia, born in the Netherlands in 1956. His 2017 work Ghost Bones sits at the very edge of conventional definitions of a book – it is housed in a flat box. Millard pulled out all stops to acquire a unique copy for the collection. The book is an environmental statement about Australia and depicts cartographic representations of the landscape. “He’s completely not bound it and he’s used different mediums. So he’s got this beautiful Japanese paper, and this is actually painted. He actually paints the images.”

Art on the Page

Noel Shaw Gallery, University of Melbourne

1 August – 14 January, 2018